IBM's Cloud Disruption

Lessons on disruption from the tech giant

I’ve been thinking a lot about investing in trends, particularly in AI. Viewed through the lens of the Innovator’s Dilemma, investing in trends becomes even more fascinating.

Some of you may have seen this graphic I put together thinking through the AI investing ecosystem:

What I find fascinating is that if you go through the same thought process for the internet, it does not yield great results:

Viewed through the lens of “internet exposure”, we likely would’ve invested in the largest companies with the most exposure to these areas. IBM, Microsoft, Intel, Cisco, Sun, Dell. That portfolio wouldn’t have yielded outstanding results.

My goal for this article is to be the first in a series of articles exploring companies that logically should have been great tech investments but weren’t.

IBM happens to be the first because they’re such a fascinating example of the Innovator’s Dilemma.

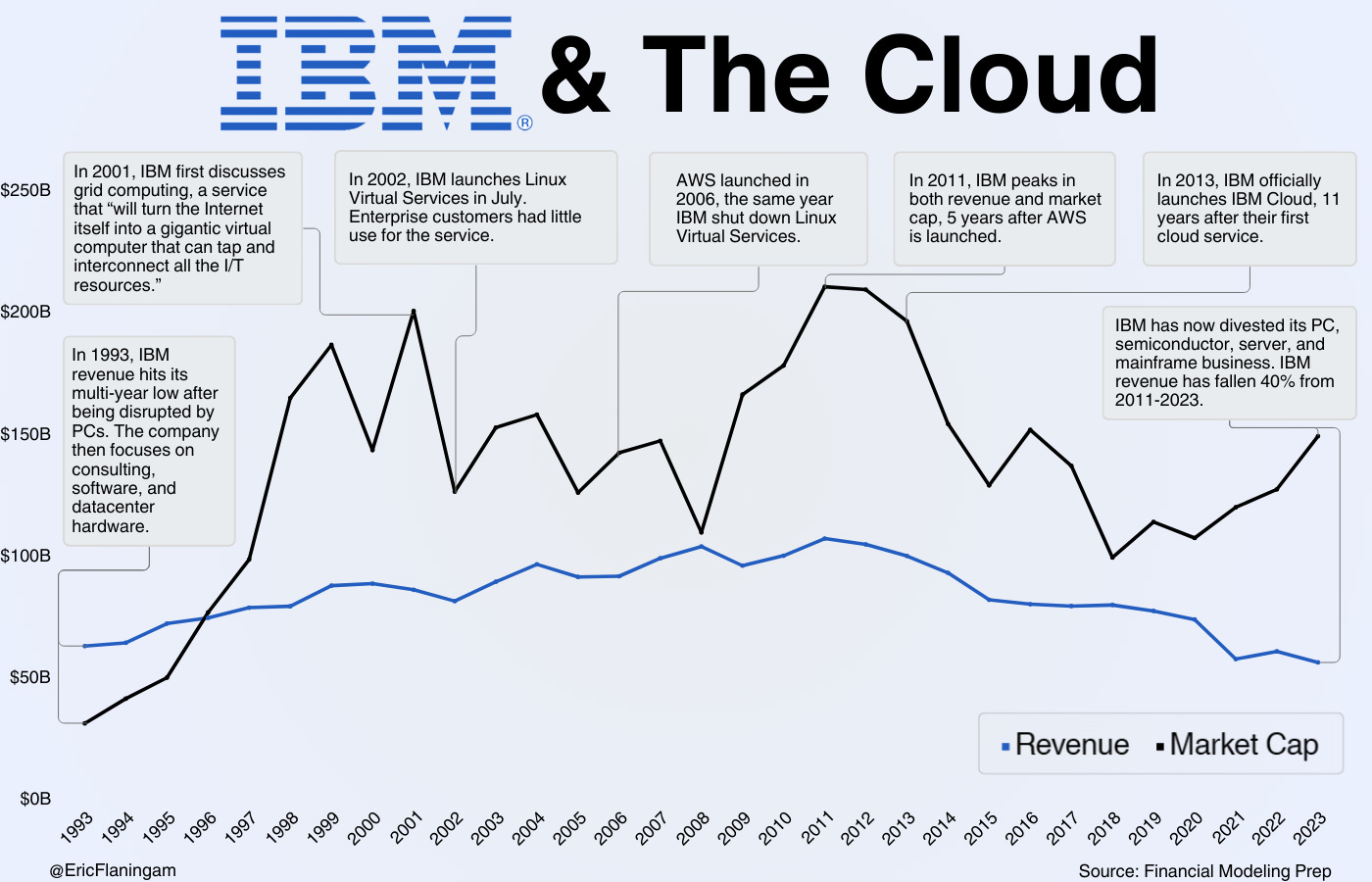

At the dawn of the internet, they had strong positions in enterprise software, data center infrastructure, and semiconductors. They also predicted the rise of the internet, mobile, and the cloud. Yet, IBM became a poor investment. The question I’ll try to answer is why. I have no intention of fully answering that in this article, but my goal is to start to develop some mental models on how to view disruption.

One final note on why I’m writing about this: The more I study disruption, the more I believe it is the most important concept in investing to understand. I believe this is a foundational piece of knowledge. In the same vein as writing out industry primers, my goal is to build the strongest possible foundational base of knowledge; I hope it’s valuable for you as well.

A Theoretical Framework for Disruption

Clayton Christensen, who was a professor at Harvard Business School, wrote the most famous theory on disruption called the Innovator’s Dilemma. The core thesis is that great companies don’t do anything wrong, but that logical business decisions lead to disruption. Companies will listen to their biggest and most important customers to decide where to focus the business. They develop increasingly complex and expensive products that their top customers will pay for. This leads to an oversupply of performance for the rest of the market at an expensive price.

At the same time, market leaders don’t want to lose their profit margins investing in every potential disruption, so they wait until the new market is large enough to invest in.

This opens the door for disruption as a new cost structure can offer a simpler service, with less functionality, at a cheaper price. Challengers can then address additional needs and work their way upmarket forcing the incumbent into “an upmarket retreat.”

Market leaders then wait to enter the new market for a few reasons: not wanting to lower margins, not wanting to threaten their current business or just underestimating competition. By the time the incumbent decides to enter the new market, it’s too late as large companies typically can’t move fast enough to compete with the more nimble challenger.

The key point is that disruptive technologies provide a new paradigm of business that challenges market leaders, who then don’t move quickly enough to fend off disruption.

IBM and the early days of the cloud

In the early 1990s, IBM was going through a reinvention after first winning and then losing the PC market. In a similar fashion to the cloud, no one thought the PC market would be as big as it became. In another example of disruption, the cost of using PCs became much more efficient for most companies than using IBM’s core product - the mainframe. So, the mainframe began a long, slow decline, as computing became decentralized with PCs.

By 1998 though, IBM had recovered by focusing on consulting, software, and maintaining its hardware business made up of mainframes, servers, and semiconductors. At this time, IBM was the world’s largest provider of data center infrastructure, the world’s largest ASIC semiconductor provider, one of the world’s largest software providers, and the world’s largest tech consulting company.

By 1999, IBM still derived the majority of its revenue from hardware:

Much of this hardware went directly into data centers, the heart of the cloud.

At the dawn of the internet, mobile, and the cloud; IBM was dominating the data center market, had a multi-billion dollar semiconductor business, and had over 500,000 enterprise customers.

Even more, IBM predicted that these trends would take over the tech world. This quote from the 1998 annual report highlights how well they knew what was coming:

You experience this every time you go online to buy a book or trade stock. Where is the transaction executed? Where is the data managed and stored? Where does the processing take place? A teeny part is handled by your PC. Most of the work is done behind the scenes, in the network, by bigger computer systems.

Businesses deploying network applications have to handle an exponential increase in the volume of interactions and transactions, and they need to do something useful with the tidal wave of information generated from those interactions. Both needs are driving the rediscovery of enterprise computing – that is, industrial-strength servers and the software that runs on them.

As the Net takes over much of the work previously performed by PCs, we’re seeing another interesting development: a proliferation of new personal computing devices – personal digital assistants, Web-enabled TVs, screenphones, smart cards and a host of products we have yet to imagine. One market research firm predicts that sales of non-PC Internet devices will surpass PCs within five years. This explosion of “information appliances” will bring computing to millions of new users – perhaps a billion people – faster and more affordably than the PC could ever have taken us.

From 1998-2002, the annual reports continue to be innovative. In 2002, they described cloud computing (they call it grid computing) for the first time:

Finally, at the 40,000-foot level, “grid computing” architectures will turn the Internet itself into a gigantic virtual computer that can tap and interconnect all the I/T resources —not just information, but also tools —across multiple enterprises.

This is the same year they launched Linux Virtual Services, a cloud service.

They also wanted to pioneer the SaaS business model, claiming IBM was becoming a company of on-demand computing. They call it e-business on-demand, which is software delivered through the internet hosted on IBM’s data centers:

All of this is what we mean by “e-business on demand,” which you will be hearing a lot about in the months and years to come. These “sense-and-respond” or “real-time” enterprises enjoy enormous competitive advantages. They are able to convert fixed costs into variable costs. They can greatly reduce inventories. And, most compellingly, they are extremely responsive to the needs of their customers, employees and partners.

In addition, an emerging technology called grid computing, built around another set of open specifications, allows the sharing and managing of separate computing resources as if they were one huge, virtual computer. This will dramatically increase utilization rates and give customers access to enormous computing capacity.

Recapping IBM’s situation in 2002:

They have:

strong market share in data center infrastructure

500,000+ enterprise customers

a leading semiconductor business with their semis in Xbox’s, Playstations, and Nintendos

successfully predicted the rise of the cloud, mobile, the internet, and IoT

a clear strategy for providing the software and hardware to enable the coming age of computing

And yet, they still end up getting disrupted..so what happened?

IBM Faces Disruption

Instead of exhaustingly walking through the next steps of the cloud for IBM, I wanted to give a summary and dive into why this happened.

IBM never really developed a cloud infrastructure business. Most of their cloud revenue came from consulting and custom engagements for large customers. Their management was focused on margins, and they didn’t see the cloud would disrupt them until too late. At the same time, internal dysfunction doomed IBM. They were focused on too many projects and didn’t get a cohesive plan for the cloud until 2021.

For a more comprehensive story of what happened, this is a great article.

So what caused this?

1. From the top, IBM was not focused on innovation.

If you read IBM’s annual reports, there’s a clear change when new CEO Sam Palmisano takes over in 2002. IBM stops talking about strategy, innovation, and “grid computing” and starts talking about reorgs, globalization, margins, and becoming business consultants.

This opening quote from 2006 sums up their focus pretty well:

I will discuss, [our results] were achieved primarily by remixing our business to higher-value segments and by driving efficiency through global integration. - IBM CEO Sam Palmisano, 2006 Annual Report

They were focused on margins, global expansion, and internal productivity. This is a distinct shift from the late 1990s when they were focused on innovation and expanding their business.

By 2006, the year AWS was launched, IBM had shut down Linux Virtual Services. IBM had stopped talking about grid computing. Their focus was on high-margin opportunities. They correctly predicted in 2007 that most data centers would need to be updated in the coming 5 years. They assumed that would be on IBM hardware, instead of seeing some of those workloads moving to the cloud.

When disruption comes, a great management team is the most important variable to success.

2. When the new market came, IBM tried to “toe the line” between the old market and the new market.

In 2009, it was becoming clear that the cloud would be important. So IBM started to focus on the cloud again, and their 2009 report gives us some insights into how they thought about the cloud:

We have also established a portfolio of cloud services that clients can access externally from IBM or offer internally to users on their own premises. And because of IBM’s track record of integrating new technology paradigms like open source and the Internet into the enterprise, we have earned the trust of clients and the industry to bring reliability and security to what is new.

They pursued the ‘Hybrid Cloud’ strategy to balance their core on-prem hardware business with their cloud business.

Christensen discusses this frequently. Initially, that logic makes sense. However, in attempting to win both markets, you doom the new business to failure. When you have fast-moving competitors taking on a new market, this strategy doesn’t work according to Christensen.

IBM further proves its flawed strategy later on in the letter:

In discussions with enterprise clients, most are initially focused on private cloud implementations, the middle ground between the traditional enterprise IT and public clouds.

By providing deployment choice, optimizing solutions based on workload characteristics and delivering complete service management capabilities, IBM is positioned as the leading cloud service and infrastructure provider for enterprises.

Selling disruptive technology to leading customers doesn’t work according to Christensen.

A key principle of the Innovator’s Dilemma is that disruptive technologies take on new markets, not old ones. In IBM’s case, their largest customers have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on IBM hardware and software. Why would they spend even more money on a service with less functionality that they could run on their own hardware?

The market leader must take on the new market as a new company. In How Will You Measure Your Life, Clayton Christensen points out that the market leader must create a new sales org, a new brand, and a new strategy to take on that new market, or else they will fail. The existing company’s best chance is to form a new segment outside of the constraints of the big company’s processes.

You then give that new segment funding and the right to kill the parent.

3. Once IBM focused on the cloud, internal constraints led them to failure.

Two internal factors led to IBM’s loss in the cloud market: a focus on AI and internal dysfunction.

With IBM not seeing much success with enterprise clients, they relaunched IBM Cloud in 2013 with the acquisition of SoftLayer…7 years after AWS was founded. At this point, IBM has more cloud revenue than AWS ($4.4B compared to $3.8B for AWS). However, much of IBM’s cloud revenue came from consulting and services.

Several factors led to this effort failing.

First, IBM wasn’t fully focused on the cloud. AI & analytics was a larger business and it didn’t disrupt their core business. It was the logical choice to pursue.

At the same time as the cloud was disrupting their core business, IBM was focused on AI. As a former IBM salesman told me,” IBM wanted to be an AI company, we weren’t really focused on the cloud.” The protocol article references a “maniacal focus on selling Watson at the height of its public awareness.” We all remember Watson in Jeopardy right?

Second, IBM’s processes were so tailored to huge clients that they couldn’t efficiently build a new business focused on smaller players.

The protocol article points to one common thread that slowed IBM’s cloud growth: customer obsession.

Over and over again during the last decade, IBM engineers were asked to build special one-off projects for key clients at the expense of their road maps for building the types of cross-customer cloud services offered by the major clouds. Top executives at some of the largest companies in the country — the biggest banks, airlines and insurance companies — knew they could call IBM management and get what they wanted because the company was so eager to retain their business, the sources said.

This is another key tenant of the Innovator’s dilemma. Customer obsession is required to win markets initially; however, a focus on large clients dooms you when new markets emerge.

Third, IBM’s internal dysfunction led to its failure in the 2010s.

SoftLayer’s technology didn’t work for enterprise customers, so IBM attempted to develop its own internal infrastructure. Incredibly, they had two competing internal architectures until 2021. An excerpt from the Protocol article:

For almost two years, two teams inside IBM Cloud worked on two completely different cloud infrastructure designs, which led to turf fights, resource constraints and internal confusion over the direction of the division. The cancellation of Genesis forced IBM to write off nearly $250 million in Dell servers (a bitter irony, in that IBM sold its own server group just before acquiring SoftLayer) that had been purchased for that project, according to one source.

And the two architectures — which IBM had intended to be compatible but due to subtle design differences, were not — became generally available within four months of each other in 2019. IBM continued to maintain two different cloud architectures until earlier this year (2021), according to one source, when the GC effort was scrapped.

This combination of lack of focus and internal dysfunction made it impossible to successfully pivot once faced with disruption.

Lessons Learned

1. Execution beats strategy every time.

Microsoft is the easiest comparison to IBM on a tech giant that needed to pivot to the cloud. It is important to note that Microsoft wasn’t caught in the same dilemma as IBM. Microsoft felt they needed to pivot to the cloud to SAVE their core business. This created an easier path to a cloud-first focus.

With that being said, Microsoft’s turnaround was still incredible. They focused their technology on the cloud at the same time they transformed their culture. Satya Nadella made culture a priority, and the new collaborative culture helped Microsoft align as a company. It’s a similar pivot Microsoft is making now to focus on AI. This leads to a valuable lesson:

Execution beats strategy every time. IBM had the perfect strategy in 1998, focusing on enabling the technology for the cloud and the internet to be built on. Yet, they failed. Microsoft focused its resources on the cloud in 2014, and it succeeded. This is largely a product of both management quality and an element of luck.

I’ve come to spend as much time studying the management of companies as I do the business itself.

The other note that I’ll add is that it’s much harder to execute on 100 projects than it is one. Verticalization is a double-edged sword. Especially for those of us investing in big tech, we should deeply study if a vertical technology stack can lead to falling behind in innovation.

2. Top-down investing in trends is a brutal challenge, using trends as a factor in bottom-up analysis is valuable.

Terry Smith articulates the challenges well in the context of AI, but it’s fair to apply it to most trends, even the ones that end up being important:

This isn’t to say not to study trends; on the contrary, the cloud and the internet created incredible investment opportunities for those who were patient and attentive.

3. Humility is vital

Finally, the more I study, the more I realize how little I know. The game of investing draws a fine line between the confidence of conviction and the humility of knowing our limitations. The goal, as I see it, is to eliminate as many unknown variables as possible.

Once we sufficiently lower the risk of misanalysis, we have to be honest with ourselves if we can reasonably predict the key drivers of a business. Oftentimes, with tech trends, we can’t. And that’s okay.

Brad Gerstner puts it well, “There’s batting average, and there’s slugging percentage…when we swing hard at the ball, runners are in scoring position, how often do we hit the ball?”

I find that great investors have the humility to know when not to swing, and the confidence to swing hard when the odds are in their favor.

As always, thanks for reading!

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not investment advice and should not be used as such. Investors should do their own due diligence before investing in any securities discussed in this article. While I strive for accuracy, I can’t guarantee the accuracy or reliability of this information. This article is based on my opinions and should be considered as such, not a point of fact. I’m a Microsoft employee, all information contained within is public information or my own opinion. I hold shares of Microsoft, Amazon, and Google

What a great article! I have always wondered why IBM ' mishandled' AI and the cloud' early on in 2009.

great article. i'd be curious to have your take on Google and how they're doing within the lens of a business at a crucial business model & org culture transition point.