The Evolution of Marketplaces

A Primer on the Past, Present, and Future of the Marketplace Business Model

A few weeks ago, I was riding in an Uber, listening to the Acquired Episode on Uber.

I had also seen a statistic that Waymo now has a 25% market share of ridesharing in San Francisco. Naturally, it made me think about Waymo’s effect on Uber.

That leads to a more interesting question: What’s the future of aggregators?

Many of the largest companies founded in the last 30 years have been aggregators. They aggregated information as supply, aggregated attention as demand, and provided a service to match the two. What happens to the aggregators in a world where attention is shifting to AI?

To answer that, we need to understand what went so right over the last two decades and what led to the success of those companies. To start, we’ll focus on a specific example of an aggregator model: the marketplace.

Now’s a particularly interesting time to study marketplaces, we’ve got:

Questions on demand: Who owns attention in an agentic world? (i.e. ChatGPT booking hotels)

Question on supply: What happens if supply can be automated? (i.e. Waymo vs Uber)

Questions on economics: Will marketplaces achieve the long-expected profits of market dominance?

This article will act as a primer on marketplaces and a framework for thinking about their future, covering:

The History of Marketplaces

The Economics & Business Models of Marketplaces

The “Late-Stage Economics” of Marketplaces like Uber

The Potential Future of Marketplaces

Without further ado.

1. The History of Marketplaces & Timing Technology Waves

Physical marketplaces developed thousands of years ago, as a means of trading resources. This started with agriculture (i.e. I’ll trade you a pound of grain for a pound of meat). Over time, marketplaces grew larger, increasing the number of buyers and sellers.

This led to an important observation: The larger the market, the more specialized the labor could be. This means the bigger the market, the better. Until it hits operational limits like space, safety, and geographical constraints.

Adam Smith would go on to observe this via the Division of Labour. He observed that when people specialize their skills and trade with others, the productivity of the society goes up!

The First Digital Marketplaces

The internet unlocked the first wave of digital marketplaces. It networked the world’s information, and unlocked the ability to aggregate that information.

As we dive into digital marketplaces, we should keep one idea in mind: business innovation is a mirror of the underlying technology that unlocked it.

In 1995, Pierre Omidyar launched AuctionWeb, which would go on to become eBay, a site "dedicated to bringing together buyers and sellers in an honest and open marketplace."

In just two years, the site would sell $500M…of Beanie Babies alone. Over the next decade, the marketplace would sell cars, jets, and even yachts. They’d acquire PayPal, Skype, and StubHub. eBay epitomized what internet marketplaces could become.

By 2000, Amazon would launch its 3rd party Marketplace as well.

The other large category of companies that rose was OTAs, or online travel agencies. Expedia was founded in 1996. Priceline was founded in 1997, on the back of a simple idea: “Airlines regularly flew only two-thirds full, with millions of seats empty. A million hotel rooms might go unused every night. We thought, what if we harnessed the Internet to drive demand, filling those planes and hotels?”

This was the beauty of marketplaces: they took unused supply and matched it with demand. As Bill Gurley put it, creating “money out of nowhere.”

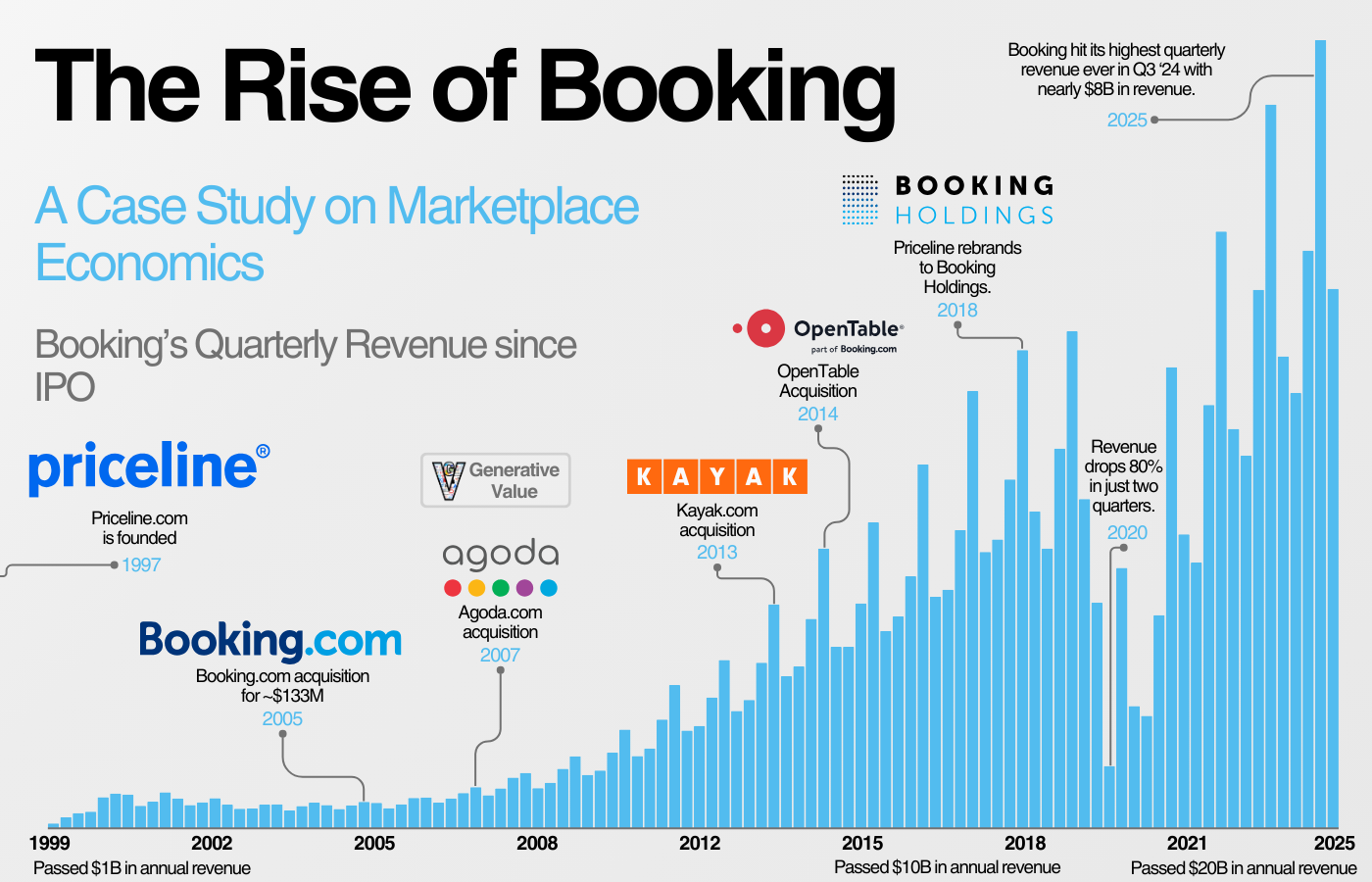

Travel marketplaces also consolidated to just a few players over the decades since their founding.

If we recall earlier: the bigger the marketplace the better, up to certain physical constraints. The internet didn’t have those constraints. Which means that it lends itself towards winner-take-most market share.

The Second Wave of Digital Marketplaces

The next wave came in tandem with a wave of disruption (the cloud) and a wave of distribution (mobile).

It’s important to point out the importance of timing in these businesses. As we laid out earlier, marketplaces tend to be winner-take-most markets. The winner is the marketplace that turns the flywheel of supply and demand the fastest. Being early almost always helps in technology, but it especially matters in marketplaces.

Over a few years, we saw the following subsequent innovations:

Google releases tools to integrate Google Maps into websites and applications in 2005.

Amazon debuts AWS in 2006.

Apple releases the iPhone in 2007 and announces it would run mobile applications.

If we’re observant at this time, we’d see there’s a new way to build applications, a new way to distribute them, and new functionality we can build out within them.

The first of our main characters was founded in 2008, with Airbedandbreakfast. For a bit of cloud lore, Jeff Bezos gave a talk to a group of Y Combinator founders in April of 2008 about how easy it is to build on AWS. It’s cheap, it’s easy, and you can iterate faster than ever before. That talk convinced the Airbnb founders to build on AWS.

Similar to Priceline a decade before, Airbnb connected unused supply and created demand for that supply. Prior to Airbnb, vacation rentals were a small market and a black box. It was risky to stay in someone else’s home! Airbnb aggregated a fragmented market, brought trust to the booking process, and created value for all sides involved.

In 2009, Uber was founded, putting instant transportation in the hands of everyone. Over time, they’d expand the “taxi market” several times over. DoorDash, the third largest marketplace of the cloud era, was founded in 2013.

To emphasize the importance of timing, the Acquired team described of DoorDash:

“DoorDash had one of the best "why now" answers of all-time: mass-market smartphone adoption (not just high-end) made three things true that were never possible before: 1. average consumers could order online conveniently, 2. couriers could plug into the network via their own devices, and 3. restaurants (most of whom didn't have wifi or desk staff) could accept orders online. Before 2013 a business like this would simply have been impossible to build.”

The promise of these marketplaces was that they’d compound via the network effects shown below:

Whoever got the marketplace flywheel turning fastest was going to win the market. The easiest way to turn the flywheel faster? Pour money into the business.

Airbnb raised over $6B as a private company. Uber raised over $20B. Lyft raised ~$5B. DoorDash ~$3B. This led to a battle of attrition. Whoever could subsidize their business long enough would eventually be entitled to the majority of the market’s profits.

Summarizing the key lessons of the marketplace:

The larger the market, the more specialized the labor could be. This means the bigger the market, the better.

With a lack of constraints in the digital world, marketplaces trend towards winner-take-most market share.

Whoever got the marketplace flywheel turning fastest was going to win the market. The easiest way to turn the flywheel faster? Pour money into the business.

2. The Economics of Marketplaces

The basic economics of marketplaces are very simple, so I won’t spend much time on them: connect fragmented buyers to fragmented sellers, take a cut off the top.

The criticism of marketplaces is that they’re commodity businesses with cost as the determining factor for victory. So the question is:

Why are they good businesses in the first place?

What variables make some marketplaces more attractive than others?

If a marketplace is a good fit for a problem set, how do they scale?

Why are marketplaces attractive business models?

To that, I’ll let Nick Sleep explain.

In Nick Sleep’s 2004 annual letter, he described what would make the best business in the world. He concludes it’s a firm that would have a huge marketplace (offering size), high barriers to entry (offering longevity), and very low levels of capital employed (offering free cash flow).

For those that know Nick Sleep’s story, Amazon would go on to become a huge % of their holdings. So he’s got to be describing Amazon here, right? Wrong! He’s describing eBay.

He goes on to say: In our opinion a business such as eBay could be the most valuable in the world. It has a huge marketplace, the biggest, an auction marketplace naturally aggregates to one player, offering high market share and high barriers to entry to the winner. Better still eBay makes the customer pay for a high proportion of the assets used in the transaction such as PCs, modems, phone lines and so forth. But best of all, the incremental assets required to grow are so small.

Some of the largest of those marketplaces can be seen here:

So marketplaces are attractive with sufficient moats, how do you build those moats?

A marketplace’s revenue is the total value that flows through an ecosystem * the take rate of the marketplace.

The “Net Revenue” divided by the “Gross Revenue” is the take rate. The long-term economics of marketplaces are determined by what % of the transaction the marketplace can take.

The take rate is ultimately determined by the competitive advantages of the marketplace. This is determined by a few variables:

Concentration of suppliers and buyers on the marketplace:

The more fragmentation, the less negotiating power from individual customers or suppliers. The marketplace’s ability to drive incremental revenue for suppliers plays into this as well: the more fragmented the industry, the more likely the marketplace drives meaningful revenue for its suppliers.

The higher the transaction amount, the lower the take rate:

Suppliers are willing to accept less of a fee for higher-priced items. For example, it’s one reason why real estate transactions don’t go through credit cards. Sellers aren’t willing to pay 3% of their transaction to the payments value chain.

Reasonable alternatives:

The less competition, the more pricing power. This competition comes in the form of both alternative marketplaces and alternatives to using the marketplace.

Value created in value-added services:

Airbnb expanded its market by adding trust into its process. Once they established that trust, no other competitor could enter the market; it’s too risky for customers. Other services include payments, quality control and authentication, insurance, and fraud prevention. All of these services are hard to replicate and build in switching costs to marketplaces.

Given that a marketplace is a good fit for the problem, how do they scale?

In large part, the competitive advantages of marketplaces are driven by scale. So how do companies build scale?

Lenny Rachitsky did some excellent work on how marketplaces scale several years back. It comes down to solving the chicken-and-egg problem. I.e., you need supply to bring in customers, but you need customers to incentivize suppliers to come to the platform.

This typically starts with constraining the marketplace to a subset of users and scaling up supply in that marketplace, like Uber starting in San Francisco.

Then it’s a constant game of scaling supply and scaling demand.

There’s no one cheat code to making this work; it’s just a constant grind for years and years until the flywheel is sustainably turning faster than competitors. If there is a cheat code, it's in raising far more capital than competitors.

3. The Late-Stage Economics of Marketplaces

At this point, we’ve laid out the economics of marketplaces, when they are a good fit, and how to scale them. All of this capital flowing into marketplaces was under one assumption: at a certain point, they would generate profits from their consolidation.

Uber and Lyft give us the model of what this looks like. It starts with the compounding network effects:

This is despite Lyft’s higher take rate (note Uber Eats has a much lower take rate, which biases this down, but Lyft’s take rate last quarter was 37% compared to Uber’s 30.3% take rate on mobility).

As market share increases, so does pricing power:

Finally, valuation reflects that:

Now, this does not mean all marketplaces will follow this path. Actually, very few have. This brings us to our final section: what does the future of these marketplaces look like?

4. What Happens to the Aggregators?

The goal of this article was to provide a primer on marketplaces (above) and a framework for thinking about their future (below).

I’ll also point out that I’m speaking in general terms, but the answer to these questions ultimately comes down to the unique supply and demand of each marketplace. Of which, I’ll leave to you all to have an opinion.

Outside of the widespread adoption of decentralized software, there are three potential outcomes for today’s large marketplaces: continued compounding, trending towards commoditization, and being out-competed by closed-loop systems.

Outcome #1: Inertia & Continued Compounding

This path is straightforward: the moats of these network-driven marketplaces lead to the predicted profitability of marketplaces. These companies will grow until they saturate the market; at which point, they’ll grow at the pace of the market. They’ll continue to become more profitable over time.

Airbnb’s brand, for example, is likely so strong that it will prevent competitors from encroaching. Amazon’s distribution network makes it brutal to encroach on their marketplace.

In these situations, the marketplace has economies of scale and pricing power. Their economics should continue to improve, just as has been predicted over the last decade.

Outcome #2: Commoditized Marketplaces

This has been the critique of the marketplace business model. If a company is primarily a demand aggregator without unique supply, then it becomes much harder to protect profits.

This highlights how hard it is to have a unique supply like Airbnb. However, all is not lost.

Take Booking and Expedia, for example, both arguably without unique supply. They are two of Google’s biggest clients, spending 31% and 50% of revenue on advertising last year. And yet, both are quite profitable businesses.

Outcome #3: Competition with Closed Loop Systems

Now, we get to the interesting part of the conversation! What if the supply of the marketplace can be automated? Closed loop systems are those where a company provides the supply directly to customers.

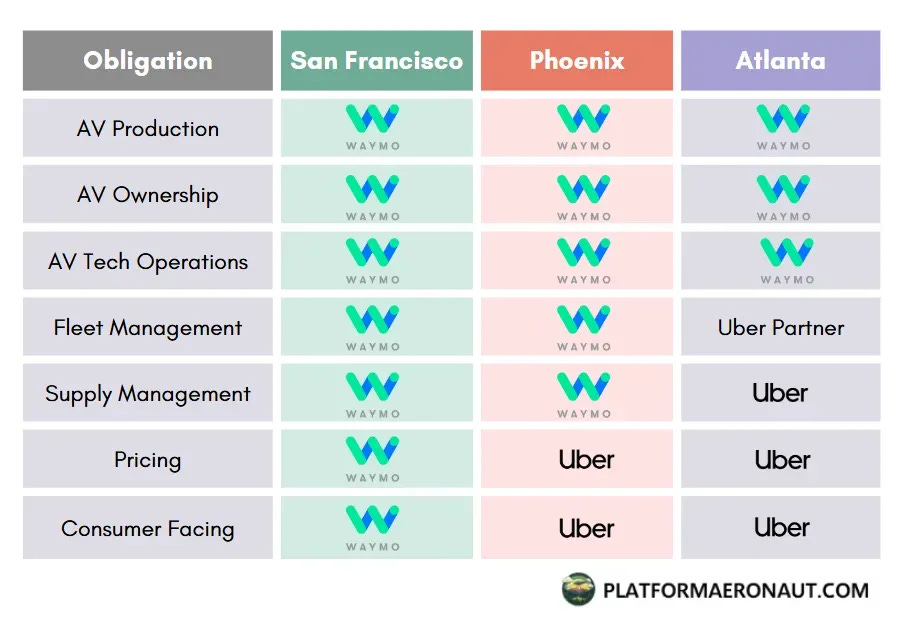

The most interesting example is the debate between Uber and Waymo.

For homogenous marketplaces, consumers pay for one thing: a consistent customer experience at the lowest price possible. If you’ve ridden in a Waymo, you know the experience is excellent. It’s no coincidence that Waymo has risen to a 25% market share in San Francisco:

Does that mean Uber is done for? I’d argue not. The beauty of marketplaces is their scalability. The beauty of closed-loop systems is their control over user experience.

These are fundamentally at odds with each other. Should Waymo build to peak or average load?

Waymo can’t build to peak, just like Taxis couldn’t build to peak! There were only 13,000 taxi cabs in NYC for a long time, compared to 100,000 rideshare vehicles in NYC.

Research suggests the optimal model may be a hybrid one like Uber and Waymo are experimenting with:

We could see a core base of closed-loop providers with a flexible marketplace network on top. This combines the benefits of top-tier user experience most of the time, with the extensibility of marketplaces on top of that.

Now, in this world, the open question is about economics. Where does value accrue? Who owns the most defensible piece of the stack, and is their business model set up to collect profits off the value chain?

I liken this to the Google vs ChatGPT debate. I’m not here to say whether one model will be dominant or the other, but it certainly doesn’t make Google’s business model better.

Finally, there’s one important question we need to ask: Who owns the attention?

Ben Thompson wrote an article back in 2015 called Airbnb and the Internet Revolution, which described how Airbnb and the sharing economy have commoditized trust, enabling a new business model based on aggregating resources and managing the customer relationship.

But what happens to that business model if you no longer manage the customer relationship?

Let’s use this commonly discussed example of ChatGPT booking you a hotel room based on your preferences.

In all likelihood, this would require a native integration between ChatGPT and Expedia or Booking.com. You ask ChatGPT to book you a hotel, it navigates Expedia for you and books the hotel. Over time, your preferences get stored in ChatGPT; you go to the OTA less.

How does that affect the business model of the OTA? Again, hard to say, but it certainly doesn’t make it better.

And by the way, I didn’t conjure this up in my head; this section was inspired by an executive conversation between DoorDash and OpenAI.

This is one of the most important second-order effects of AI, and one I don’t have a good answer to today. But hey, a mediocre answer to a great question is more important than a great answer to a mediocre question.

As always, thanks for reading!

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not investment advice and should not be used as such. Investors should do their own due diligence before investing in any securities discussed in this article. While I strive for accuracy, I can’t guarantee the accuracy or reliability of this information. This article is based on my opinions and should be considered as such, not a point of fact. Views expressed in posts and other content linked on this website or posted to social media and other platforms are my own and are not the views of Felicis Ventures Management Company, LLC.

Excellent Post!

Hello there,

Huge Respect for your work!

New here. No huge reader base Yet.

But the work has waited long to be spoken.

Its truths have roots older than this platform.

My Sub-stack Purpose

To seed, build, and nurture timeless, intangible human capitals — such as resilience, trust, truth, evolution, fulfilment, quality, peace, patience, discipline, relationships and conviction — in order to elevate human judgment, deepen relationships, and restore sacred trusteeship and stewardship of long-term firm value across generations.

A refreshing take on our business world and capitalism.

A reflection on why today’s capital architectures—PE, VC, Hedge funds, SPAC, Alt funds, Rollups—mostly fail to build and nuture what time can trust.

“Built to Be Left.”

A quiet anatomy of extraction, abandonment, and the collapse of stewardship.

"Principal-Agent Risk is not a flaw in the system.

It is the system’s operating principle”

Experience first. Return if it speaks to you.

- The Silent Treasury

https://tinyurl.com/48m97w5e