Thoughts on the Hyperscalers (Q3 '25 Update)

A shifting value chain (OpenAI and Anthropic gaining importance) and what it means for the cloud providers; also market share, CapEx, and revenue growth updates.

I write one quarterly series on Generative Value: a quarterly update on the state of the hyperscalers (Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and kind of Meta). This quarter felt unique to me.

If we take a step back, just over two years ago, OpenAI had built an incredible research team and consumer product, but it felt like they still had a long way to go to be viewed in the same light as the other tech giants.

Now, that’s changed. OpenAI and Anthropic have helped catalyze the largest computing infrastructure buildout in history. Evidenced by the scale of the deals they’ve signed with the hyperscalers in the last quarter, they’ve become the two most important cloud customers in the world.

In summary, they’ve created their own segment of the tech value chain, and put themselves at the center of the largest players in tech.

Below are some thoughts on what that shift means, along with updated data (market share, revenue growth, CapEx) from the hyperscalers.

1. The Value Chain is Shifting

All else equal, it’s best to be the consolidated piece in the value chain, and sell to a fragmented set of customers (less competition, more pricing power).

Before OpenAI and Anthropic’s rise, the cloud providers were selling to a massively fragmented buyer base. Even the largest customers made up just a fraction of cloud revenue.

That’s changing. Let’s take a look at the slew of announcements over the last quarter or two:

OpenAI and Anthropic have now positioned themselves squarely in the middle of the tech giants, and aligned incentives for everyone to benefit from their success. I’ll just leave you with this Paul Graham quote about Sam Altman (back in 2008):

“When we predict good outcomes for startups, the qualities that come up in the supporting arguments are toughness, adaptability, determination… Sam Altman has it. You could parachute him into an island full of cannibals and come back in 5 years and he’d be the king.”

It certainly feels like OpenAI is king right now.

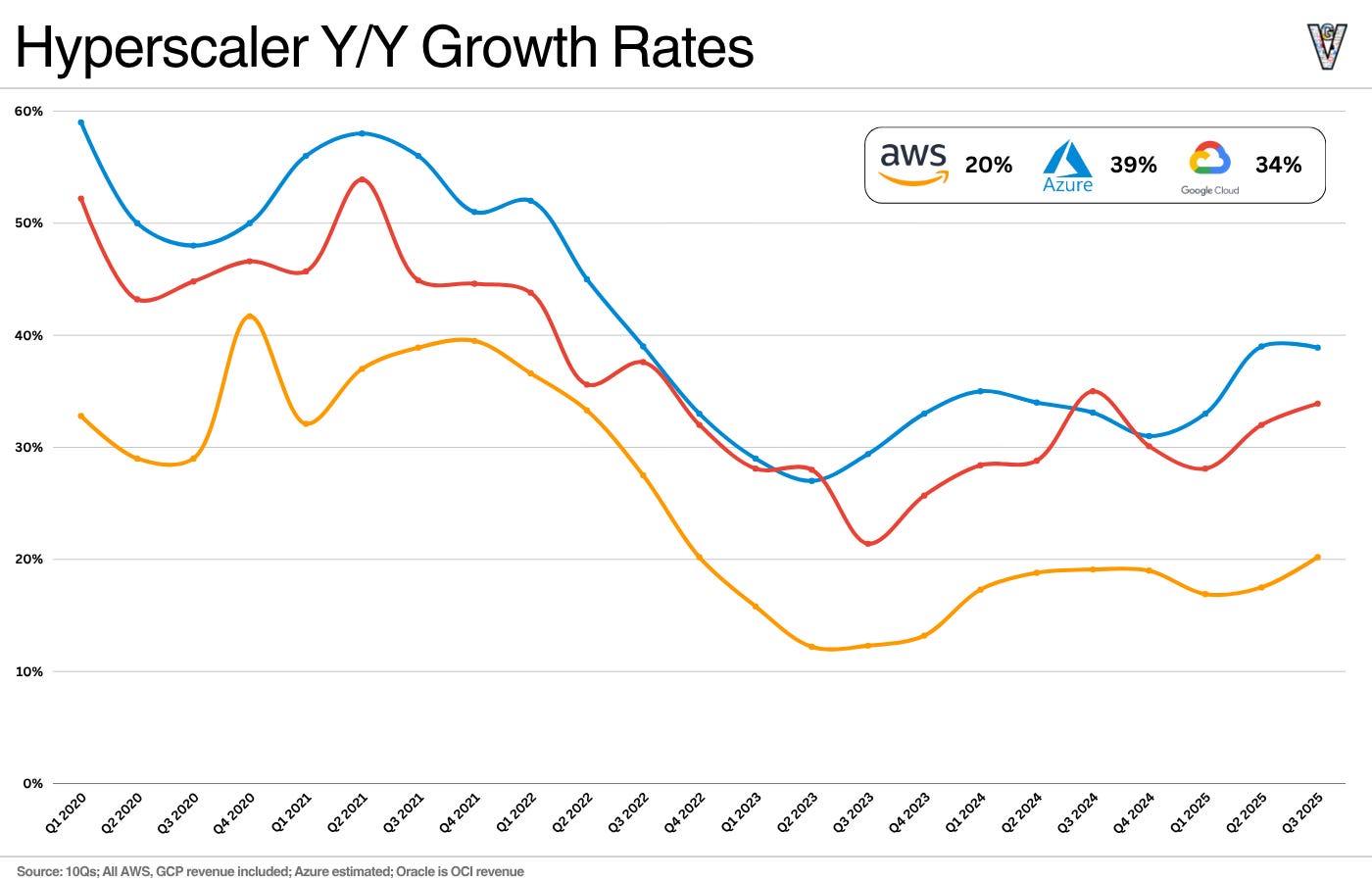

Along with Anthropic, they’ve created the largest greenfield (net new revenue opportunity) creation the hyperscalers have ever seen. Take a look at AWS’ re-acceleration here, driven by the growing partnership with Anthropic:

It may not look that drastic, but for AWS, that’s at a $132B revenue run rate! According to Semianalysis:

AWS has well over a gigawatt of datacenter capacity in final stages of construction for its anchor customer. AWS is building datacenters faster than it ever has in its entire history. And there’s much more on the horizon.

I can’t confirm this, but it’s likely Google’s acceleration is driven by Anthropic as well.

In summary, the foundation model providers have created the largest greenfield revenue opportunity ever for the hyperscalers. And the question becomes: what are the hyperscalers willing to do to capture it?

2. The hyperscalers are all capacity constrained, but how much CapEx are they willing to invest, and at what economic profile?

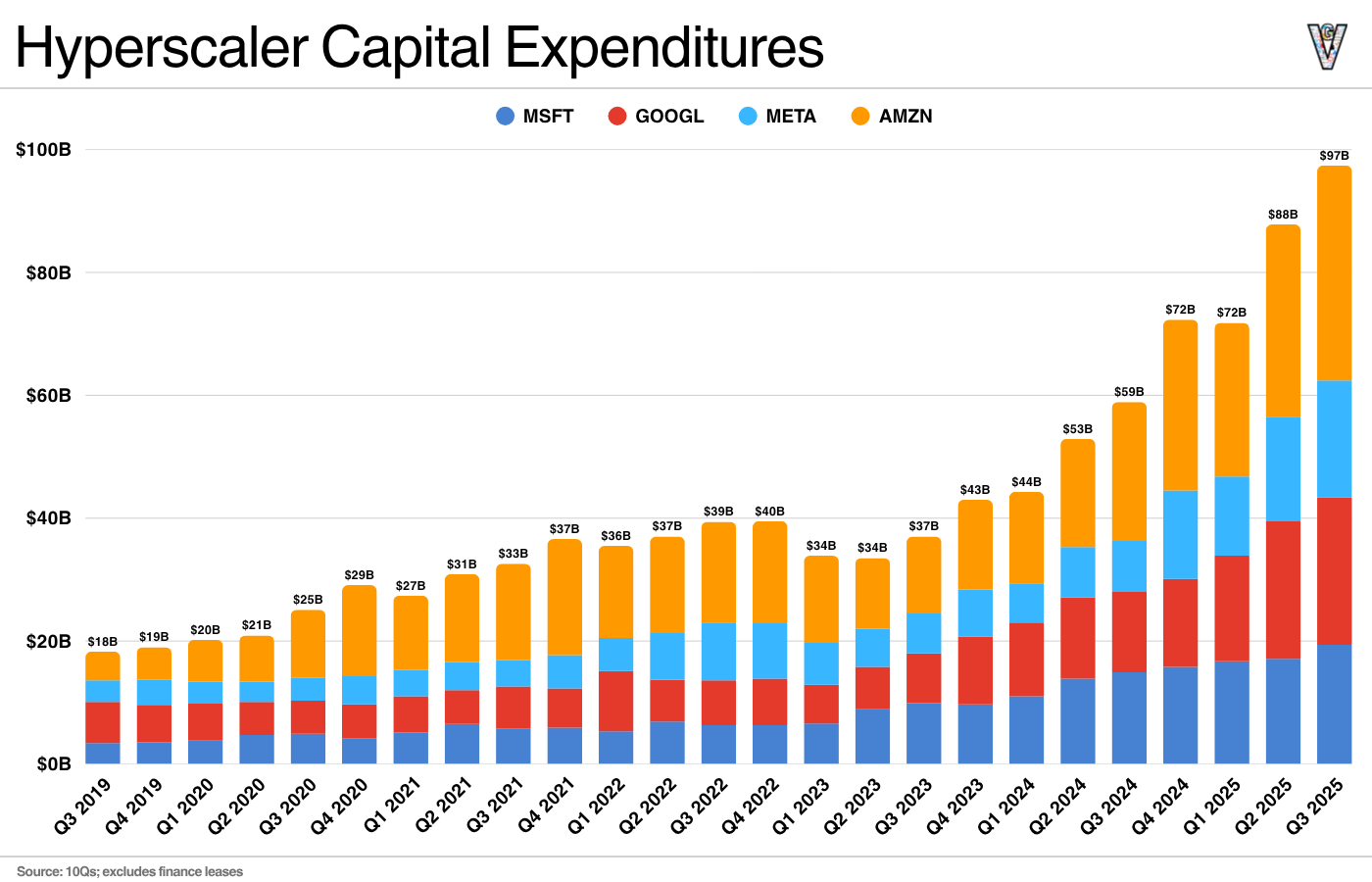

Hyperscaler CapEx nearly hit $100B last quarter. If we include data center leases ($11B+ from Microsoft last quarter), it well exceeds $100B.

For all the talk of a bubble, the hyperscalers are still capacity-constrained today. And the hyperscalers are investing to ensure they maximize the amount of durable, recurring revenue they can capture.

Now I’m still of the belief there will be a glut at some point (where we overbuild for a period of time, leading to decreased investments). For what it’s worth, so is Sam Altman:

“There will come a glut for sure and whether that’s in two to three years or five to six I can’t tell you, but it’s going to happen at some point, probably several points along the way. There’s something deep about human psychology here and bubbles.”

But demand is simply greater today than many were expecting (including myself, and shame on me, I spend my days talking to early-stage startups growing like wildfire).

Take a look at the RPO numbers:

Oracle: Q1 Remaining Performance Obligations $455 billion, up 359% in both USD and constant currency

Microsoft: Microsoft Corporation Cloud revenue surpassed $49 billion, up 26% year over year, and our commercial RPO grew over 50% to nearly $400 billion with a weighted average duration of only two years.

Google: Google Cloud’s backlog increased 46% sequentially and 82% year over year, reaching $155 billion at the end of the third quarter.

Amazon: Backlog grew to $200 billion by Q3 quarter end and doesn’t include several unannounced new deals in October, which together or more than our total deal volume for all of Q3.

$1.2T in backlog for these companies! The hyperscalers will continue to invest until they see signs we’re close to an equilibrium of supply and demand. Quite simply, this will be the largest driver of market share changes for the foreseeable future.

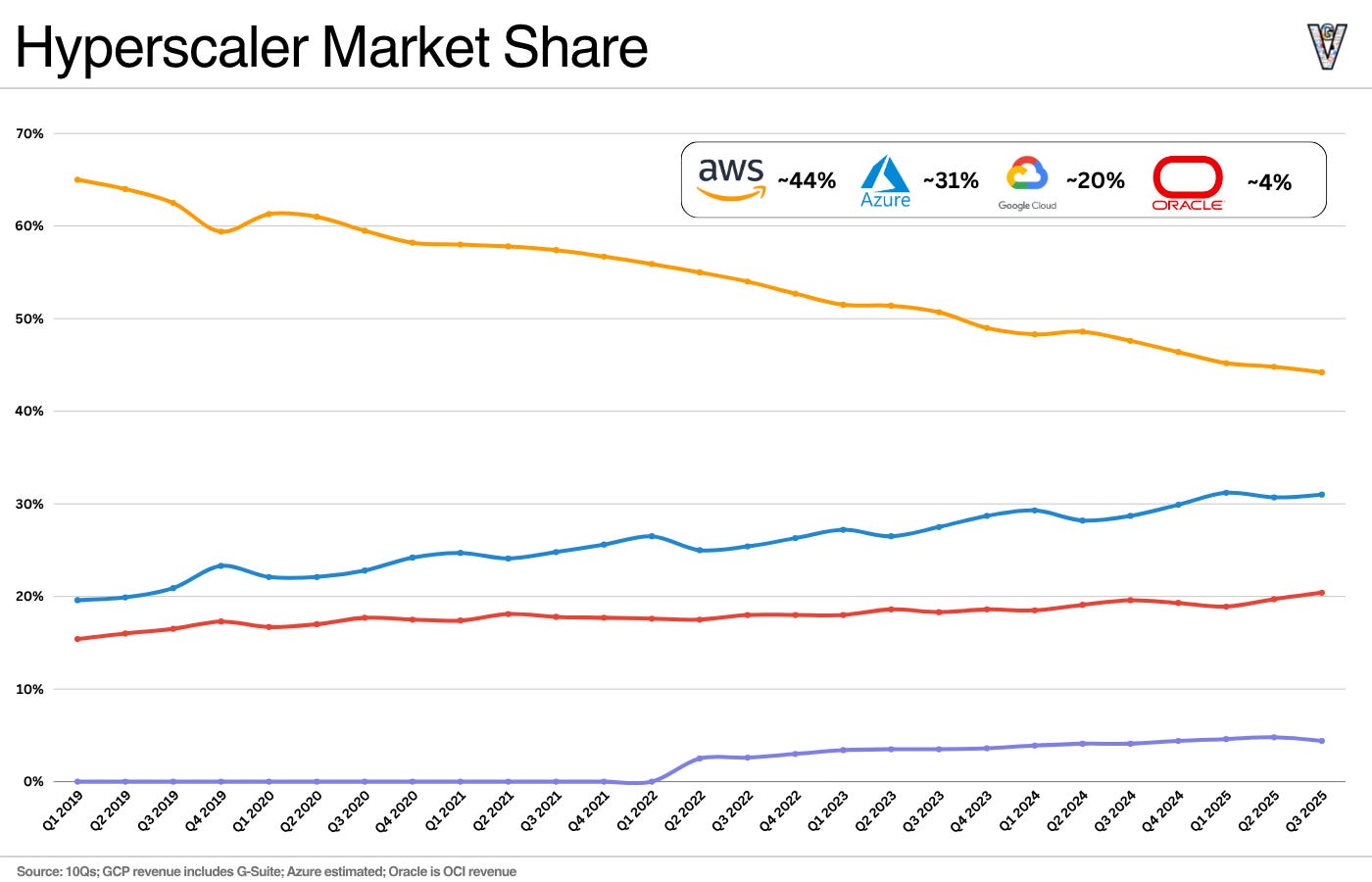

3. For the time being, the largest driver of market share changes will be foundation model revenue.

You could argue the biggest driver of market share changes over the next few years will be who can capture the majority of this greenfield opportunity from OpenAI and Anthropic. We’re already seeing that start to take hold with Microsoft’s market share gains from OpenAI’s computing needs, already generating tens of billions in revenue for Azure.

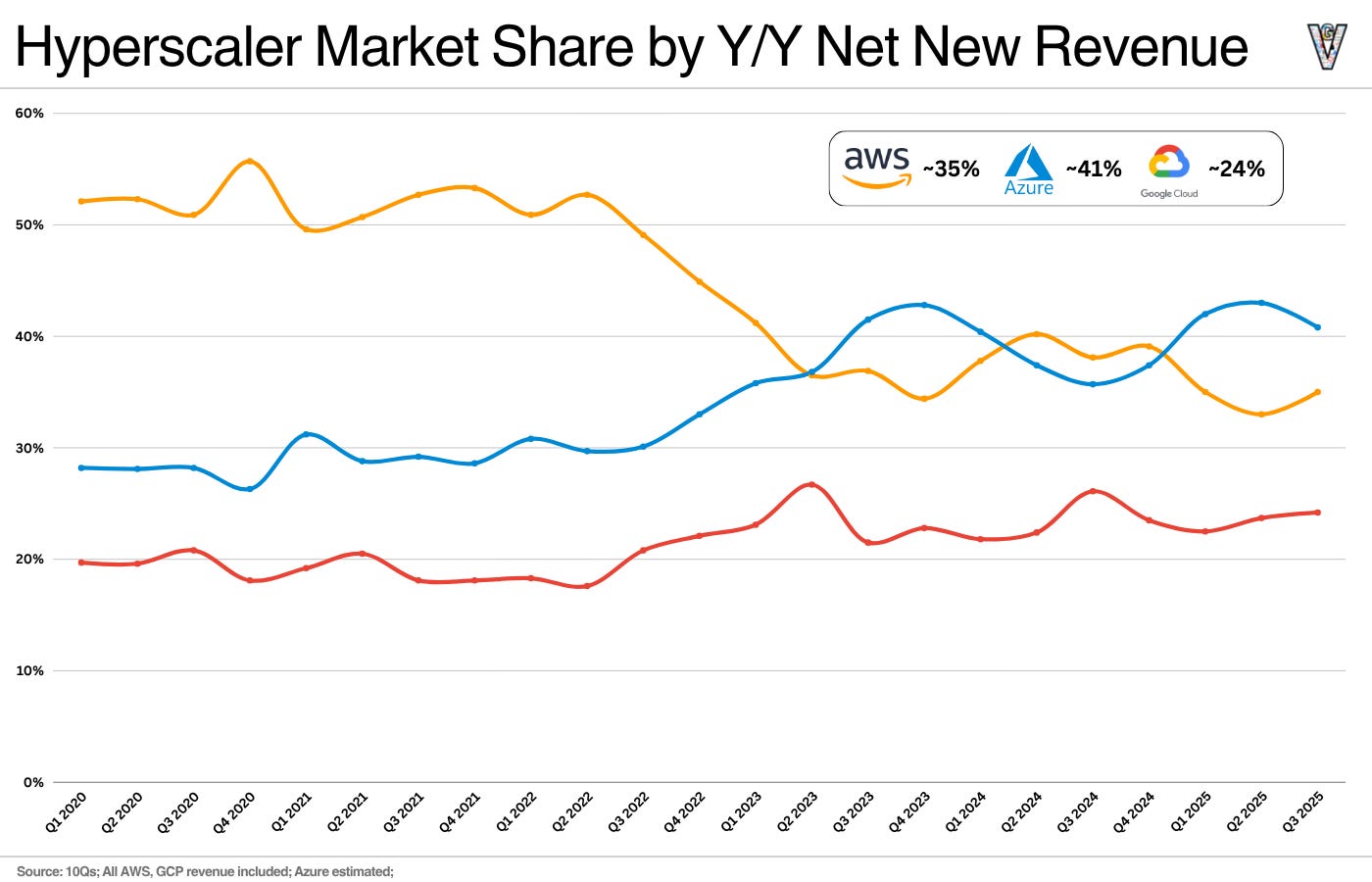

A better way to view market share changes is through Y/Y net new revenue: of the net new cloud revenue generated over the last four quarters, how much did each capture?

Through that lens, it becomes clearer how much Azure benefited from the OpenAI spend and how important the Anthropic partnership is for Amazon:

It should go without saying, but it’s also important to call out that the profitability of that revenue is important!

4. The economics of that revenue matter.

It’s easy to get caught up in the short-term market share changes from CapEx investments, but it’s also critical to remember that the revenue needs to be durable and/or profitable (should be both) for it to be high-quality revenue for the cloud vendors.

This leads to the risk-reward equation for the hyperscalers: what are they willing to do to capture this revenue opportunity?

Microsoft has been the most vocal about being selective with the types of workloads they take on, and they continue to drop hints of how they’re handling the risk of these CapEx investments.

Derisking through investing in short-lived assets and leases, reducing the long-term balance sheet exposure as much as possible.

The way to think about that, and you saw it this quarter in particular and as we talked about twenty-six, the remainder, number one, we’re pivoting toward increasingly, we talked about this short-lived assets, both GPUs and CPUs. Again, we talk about all these workloads are burning both. - Satya, Microsoft Earnings Call

It’s okay to be early, as long as investments are within the ballpark of reason, compute demands will eventually catch up. They’re okay with overbuilding by a few quarters.

So we spent a lot of time building out that infrastructure. Now we’re continuing to do that also using leases. Those are very long-lived assets as we’ve talked about, fifteen to twenty years. Over that period of time, do I have confidence that we’ll need to use all of that? It is very high. - Satya, Microsoft Earnings Call

They’ve underestimated compute demand so far, and don’t want to underinvest.

[Demand] is very high. When I think about sort of balancing those things, seeing the pivot to GPU/CPU short-lived, seeing the pivot in terms of how those are being utilized. We are, and I said this now, we’ve been short now for many quarters. I thought we were going to catch up. We are not. Demand is increasing. It is not increasing in just one place.- Satya, Microsoft Earnings Call

In summary, Microsoft is doing everything they can to capture ~durable~ greenfield opportunity without putting their balance sheet at risk to do so. Amazon and Google have talked less about this publicly, but we have to assume they’re having the same conversations in their boardrooms.

Satya alluded to this in the BG2 podcast:

Sometimes you may have to say no to some of the demand including some of the OpenAI demand. Because sometimes Sam may say ‘hey, build me a dedicated multi-gigawatt data center in one location for training.’ Makes sense from an OpenAI perspective, doesn’t make sense from a long-term infrastructure buildout for Azure.

It seems he was alluding to Oracle in this comment, which brings me to my final point.

5. Expected value vs expected utility is the final piece of the puzzle to understand these CapEx investments.

So the lens of huge greenfield opportunity + how much investment risk are the hyperscalers willing to take on to capture that opportunity explains much of the changes happening in the cloud market.

But it doesn’t fully explain the last update I haven’t discussed: Oracle’s MASSIVE RPO backlog and commitment from OpenAI.

And they’re dipping into the honeypot of leverage to get into the AI CapEx game. From Doug O’Laughlin:

There is no way for Oracle to pay for this with cash flow. They must raise equity or debt to fund their ambitions. Until now, the AI infrastructure boom has been almost entirely self-funded by the cash flows of a select few hyperscalers. Oracle has broken the pattern. It is willing to leverage up to hundreds of billions to seize a share.

So why are they willing to do this when others aren’t?

My interpretation is this: the other hyperscalers are making their best guess expected value calculation while Oracle has an expected utility calculation they’re making.

Warren Buffett explained expected value simply here:

“Take the probability of loss times the amount of possible loss from the probability of gain times the amount of possible gain. That is what we’re trying to do. It’s imperfect, but that’s what it’s all about.”

BUT let me introduce the idea of expected utility. From Michael Mauboussin:

Economists typically translate expected value into expected utility, an idea that Daniel Bernoulli, a mathematician, introduced in 1738. Utility is a measure of satisfaction and varies from person to person based on individual preferences.

In uncertain conditions, individuals will optimize for expected utility rather than solely expected value. For example, if a favorable casino offered a gambler a bet that they have positive expected value on, BUT the catch is they have to bet their home on it. A person with one home should not make that bet, but someone with ten homes should. (I have no doubt this is deeply flawed to any economist reading this article.)

Whether or not Amazon, Google, and Microsoft lever up to invest even more in this boom, there’s no additional utility for them. They’ll still be one of the big three cloud vendors.

But Oracle, by taking the additional risk with leverage, DOES get expected utility from this. They can move from being a distant fourth-place cloud vendor, to becoming one of the “big four” cloud vendors.

So when you ask Larry Ellison if he’d rather play it safe and stay where they’re at, or make the bet others aren’t if the result is a state change in how Oracle is viewed, he’ll take that bet every time.

As always, thanks for reading!

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not investment advice and should not be used as such. Investors should do their own due diligence before investing in any securities discussed in this article. While I strive for accuracy, I can’t guarantee the accuracy or reliability of this information. This article is based on my opinions and should be considered as such, not a point of fact. Views expressed in posts and other content linked on this website or posted to social media and other platforms are my own and are not the views of Felicis Ventures Management Company, LLC.

My glorious king is back. The day got a bit sunnier

What's interesting to me is how much equity BigTech has in BigAI. Interesting thoughts.