TSMC: The Index on Technology

A deep dive on TSMC: How TSMC disrupted the semiconductor industry, its current state, and its path ahead.

TSMC is one of the greatest stories in business history, bar none. Morris Chang, a former rising star in the semiconductor industry, faced career setback after career setback. Eventually, founding TSMC through Taiwan’s innovation department (ITRI), although he didn’t get any equity in TSMC! But as history shows time and time again, disruption comes unconventionally.

TSMC introduced the foundry business model to the semiconductor industry in 1987, allowing companies to outsource chip manufacturing, taking advantage of economies of scale and Asia’s cheap labor. This would unlock a new wave of semiconductor companies and make the idea of a “semiconductor startup” much more feasible.

Over the next 30 years, TSMC would reshape the technology industry around it. Now, it’s the 11th highest valued company in the world, it manufactures the vast majority of the world’s most advanced chips, and it’s become an index on the world’s most advanced technologies.

This is my (humble) attempt at covering TSMC in one article, a fool’s errand perhaps! We’ll cover:

TSMC’s Past: How TSMC reshaped the semiconductor industry

TSMC’s Present: The moats of TSMC

TSMC’s Future: The variables likely to determine its future

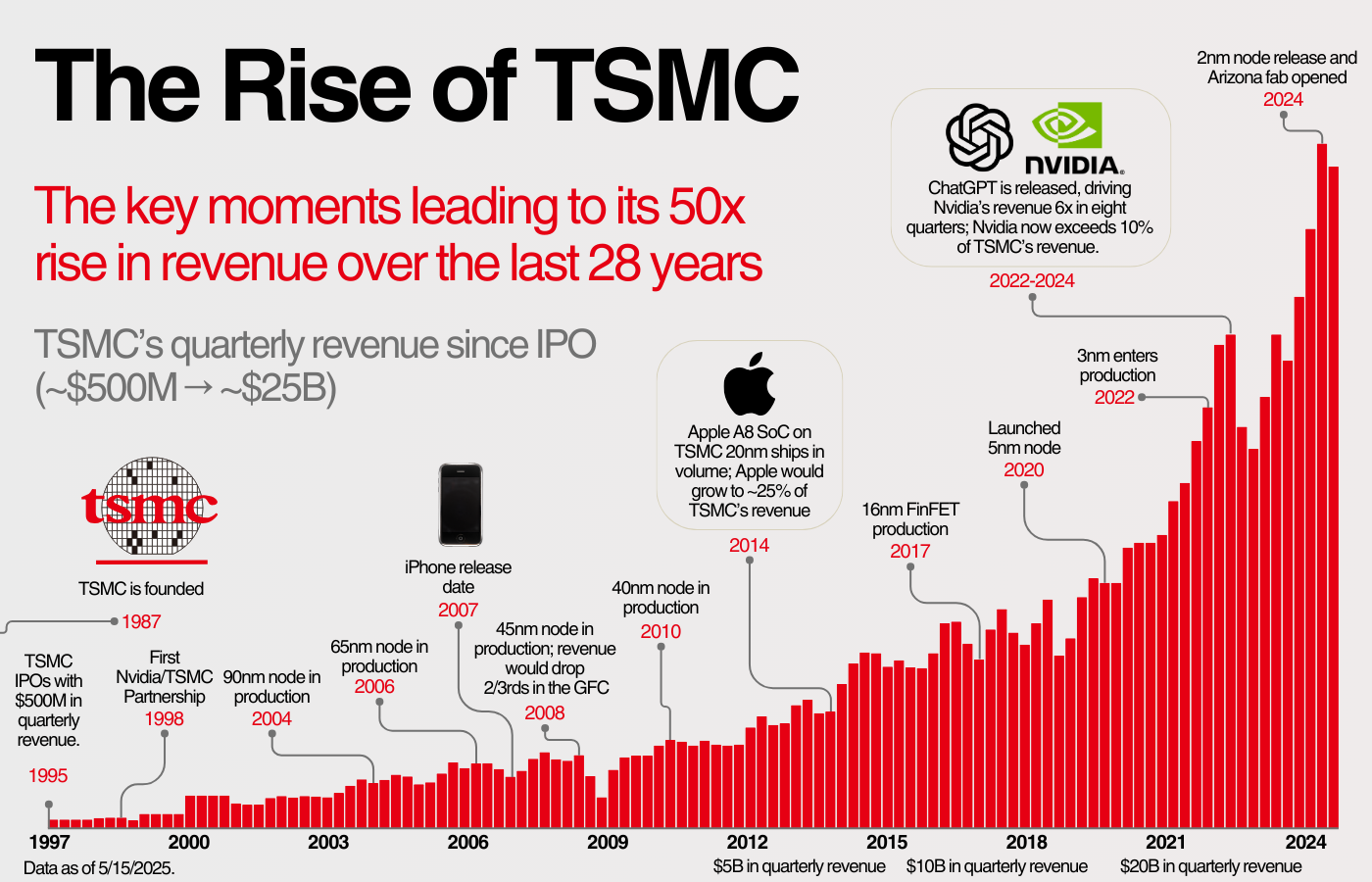

See a summary of that journey here:

Onward.

1. How TSMC Reshaped The Semiconductor Industry

Two ideas laid the groundwork for TSMC’s founding.

As semiconductor manufacturing got more complex, the barrier to entry for new companies got higher.

Morris Chang believed more semiconductor companies would be founded if startups didn’t need to build a fab to start producing chips.

In 1987, when TSMC was founded, the world’s largest semiconductor companies were vertically integrated: designing their chips (sometimes with their own software and machines), building fabs, and manufacturing chips.

We had just started to see the rise of the modern EDA providers (Cadence Design Systems was doing ~$500M in revenue) and the modern semicap companies (Applied Materials was also doing ~$500M in revenue). But the vast majority of the industry’s revenue went to vertically integrated chip manufacturers:

Per Moore’s Law, semiconductors were getting more complex, which leads to one important observation on the evolution of industries: complexity necessitates specialization.

Morris Chang, through his experience at Texas Instruments, believed more people would start semiconductor companies if they didn’t need to build fabs. Through a winding path, he ended up at Taiwan’s Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI), where he’s effectively forced to resign. In his own words, he wonders if he’s risen to the level of his incompetence.

Now, he did have one successful accomplishment at ITRI: the founding of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company.

TSMC’s Rise

TSMC’s early customers follow the disruption playbook exactly: large companies like Intel contract with TSMC to manufacture their lagging-edge chips to free up space for their high-margin leading-edge chips.

Because the margins are worse at the lagging edge, TSMC was forced to innovate. They built new fabs, pioneered new manufacturing techniques like SMIF wafer-carrying pods, and took a chance on a new lithography company called ASML.

After a couple of years, Morris’ thesis on fabless companies comes to fruition. Qualcomm, Nvidia, Broadcom, and Marvell (founded 1985, 1993, 1991, and 1995) all pursued the fabless business model.

The value prop of the fabless model was this: With TSMC, fabless companies innovate faster, have lower CapEx, and better operating margins. TSMC, in turn, gets manufacturing volume, which slowly compounds in efficiency to draw in more customers, keeping the flywheel going.

As modularization unlocks specialization, this new ecosystem of fabless companies outperforms the old. TSMC continues to compound their learnings in manufacturing, slowly encroaching on the leading-edge.

By 2000, 60% of TSMC’s revenue comes from fabless companies. Over the next decade, the fabless model would emerge as the clearly superior business model, with AMD spinning off their fabs in 2009. Intel would be the last leading-edge logic integrated manufacturer.

However, TSMC would see increased competition as well, prompting Chang’s 2009 return (from a retirement in 2005). He emphasized one point on his return: focus. The core foundry business is the company’s priority, and that’s what they’d focus on.

They created a wave of fabless chip companies and it was Morris’ intention to ride that wave.

The Apple Partnership and TSMC’s 2010s

In the early 2010s, TSMC started manufacturing chips for Apple. For TSMC, it meant an initial investment of $9 billion dollars and devoting 6000 employees to building a dedicated plant for Apple in just 11 months. For Apple, it meant “no backup plan.”

Over the next decade, Apple would grow to ~25% of TSMC’s revenue, or about $18B worth. In return, TSMC gave Apple preferred access to the leading-edge nodes.

In parallel, the cloud was becoming the preferred model for computing, further expanding the world’s computing demands. Leading up to the AI moment, which, as we all know, further expanded the world’s computing demands.

While these trends massively expanded the semiconductor market, TSMC consolidated the foundry market:

In twenty years, TSMC went from one of 26, to one of two. It was the perfect combination of growing pie and TSMC’s slice getting bigger.

To summarize TSMC’s journey:

They introduced the foundry business model to the industry.

That unlocked a wave of fabless chip companies.

Three tailwinds led to TSMC’s meteoric rise: a growing semiconductor industry, increasing importance of fabless chip companies, and increasing market share of TSMC.

That brings us to the current state of TSMC.

2. The Moats of TSMC

Instead of exhaustively covering TSMC’s technology and revenue, I’ll link to two great pieces covering them: Construction Physics’s “How to Build a $20B Semiconductor Fab” and Fabricated Knowledge’s latest TSMC update.

For a quick summary on financials, TSMC surpassed $25.5B in quarterly revenue last quarter, up 35% Y/Y, with a gross margin of 58.8% and a net income margin of 43.1%:

Instead, I want to focus on what I see as the clearest competitive advantages of TSMC (outside of just monopoly from sheer technical complexity):

1. TSMC’s Economies of Scale

Manufacturing ultimately comes down to constant, subtle improvements that compound over time. This makes volume especially important, and once those advantages compound, it becomes increasingly challenging for competitors to break in.

For TSMC, the process goes like this:

Invest CapEx, primarily into fab equipment like ASML’s machines, into new fabs at the leading edge.

Depreciate those costs over 5 years on the P&L statement. At the same time, those fabs get increasingly profitable on unit economics as the process gets better.

After the fab is fully depreciated, use those profits to fund R&D and CapEx into new process nodes.

This results in leading edge nodes being unprofitable for the first few years, followed by strong profitability to fund more leading edge nodes:

All the while competitors have less volume at trailing edges, worse yields at the leading edge, and fight to maintain the ability to manufacture at the leading edge.

2. The Collaboration of the Semiconductor Industry

Secondly, as semiconductor complexity gets harder to scale, TSMC has to partner with both suppliers and customers to ensure chips can be manufactured.

The industry’s gains are coming from (1) improvements in EDA tools, (2) improvements in design, (3) improvements in semicap tooling to further increase transistor density, (4) improvements in packaging these components together more efficiently, and (5) the foundry’s ability to integrate all of these improvements together.

It’s not easy for new entrants to break into any piece of that workflow, nonetheless the foundries, who are at the center of the process:

With customers, an engagement with TSMC is typically a multi-year process. TSMC will offer a Process Design Kit (PDK) that’s like a detailed instruction manual for how/what features will be manufactured. Customers will pay an upfront cost for how much work and customization is required. They’ll then pay per wafer produced.

For a company to switch fabs, they’ll need to switch PDKs, re-design chips with the new fab, test to ensure there aren’t defects, and lose out on the sunk costs of the prior relationship.

And that’s if there’s even another viable alternative on the market!

3. Position in the Value Chain

Austin Lyons wrote an exceptional article called ”Monopsony and TSMC”, describing what happens in a market when there’s only one buyer. And while we aren’t quite there with TSMC, that’s the logical extreme we’re approaching.

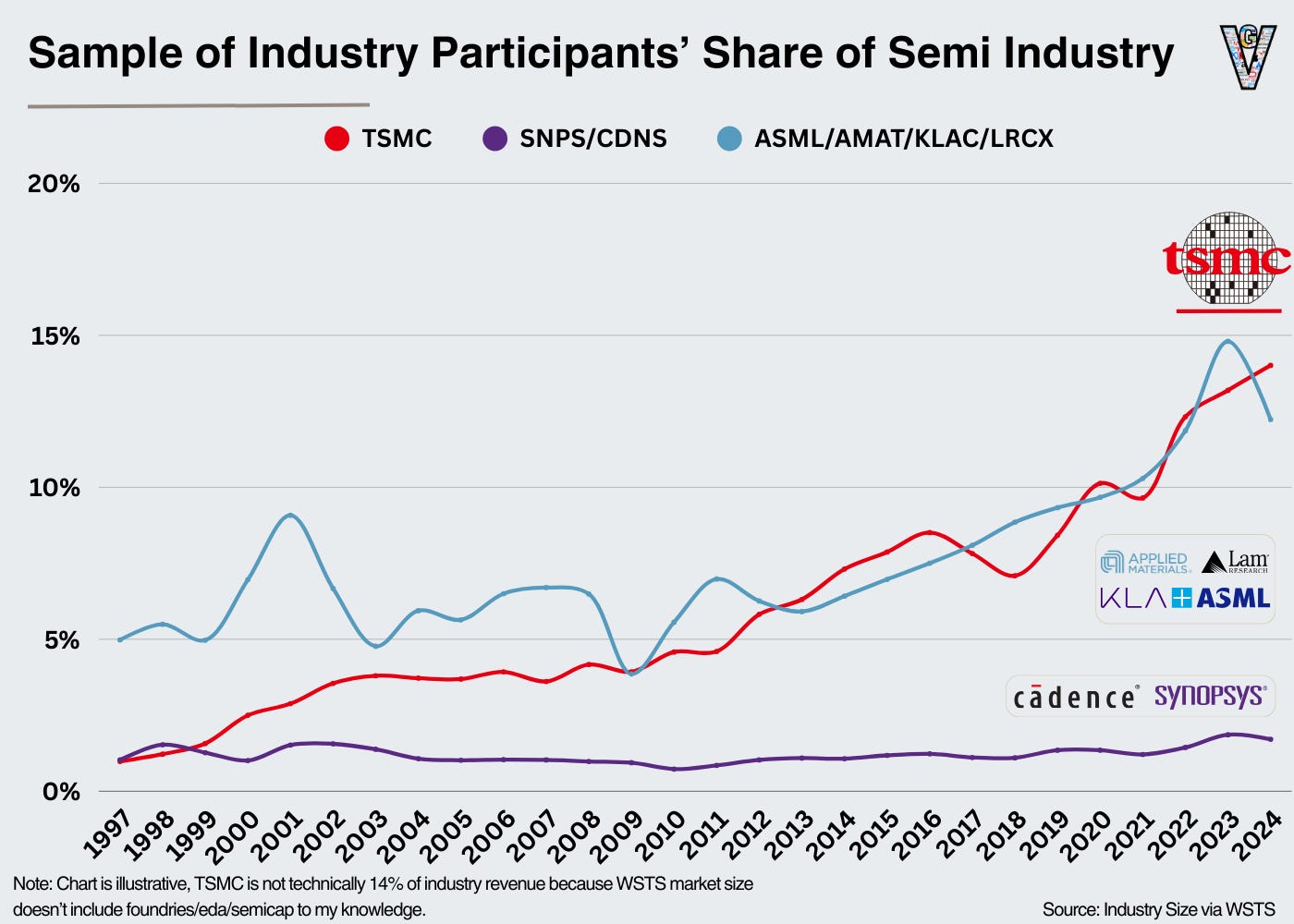

TSMC’s importance in driving forward semiconductor progress combined with their increasing market share has allowed them to take an increasing share of revenue and profits from the industry:

Because they’ve become the bottleneck of the industry, they have extreme pricing power. Now, they have very healthy margins and no incentive to squeeze their customers or suppliers on costs. Regardless, all else equal, every industry participant would prefer a fragmented supplier and customer base. And both sides of the value chain have to come to TSMC.

4. Those competitive advantages have allowed TSMC to take an increasing amount of market share:

While the numbers aren’t public, this number is much higher at the leading edge.

Depending on who you ask, TSMC has two to three potentially credible competitors at the leading edge in the near future: Intel, Samsung, and SMIC:

Today, TSMC is the clear dominant player in foundries.

There are two primary risks to TSMC that I’m monitoring:

A disruptive technology doesn’t emerge to make semiconductor manufacturing cheaper and easier.

Semiconductor manufacturing continues to drive computing performance improvements.

These two variables ensure TSMC is still leading and driving forward semiconductor scaling, which means they can maintain or increase (1) their share of foundry revenue and (2) their share of customer expenses (i.e. what % of spend of their COGs go to TSMC).

For example, chiplets could fit the bill for a disruptive technology. They could push a higher % of spend towards advanced packaging, which has lower competitive advantages compared to wafer manufacturing. Perhaps a primer on chiplets is due in the future.

3. The AI Opportunity and the Path Ahead

I want to simplify the variables that matter to TSMC as much as possible. First and foremost, TSMC is a customer service company. The success of TSMC is the success of their customers. Those customers broadly fall into two categories:

Edge devices via Apple, Qualcomm, MediaTek

AI & Data Centers via Nvidia, AMD, Broadcom, Intel, and the Hyperscalers

Apple and Nvidia made up 22% and 12% respectively of TSMC’s revenue in 2024. From 2022, we have estimates of who the other largest customers are:

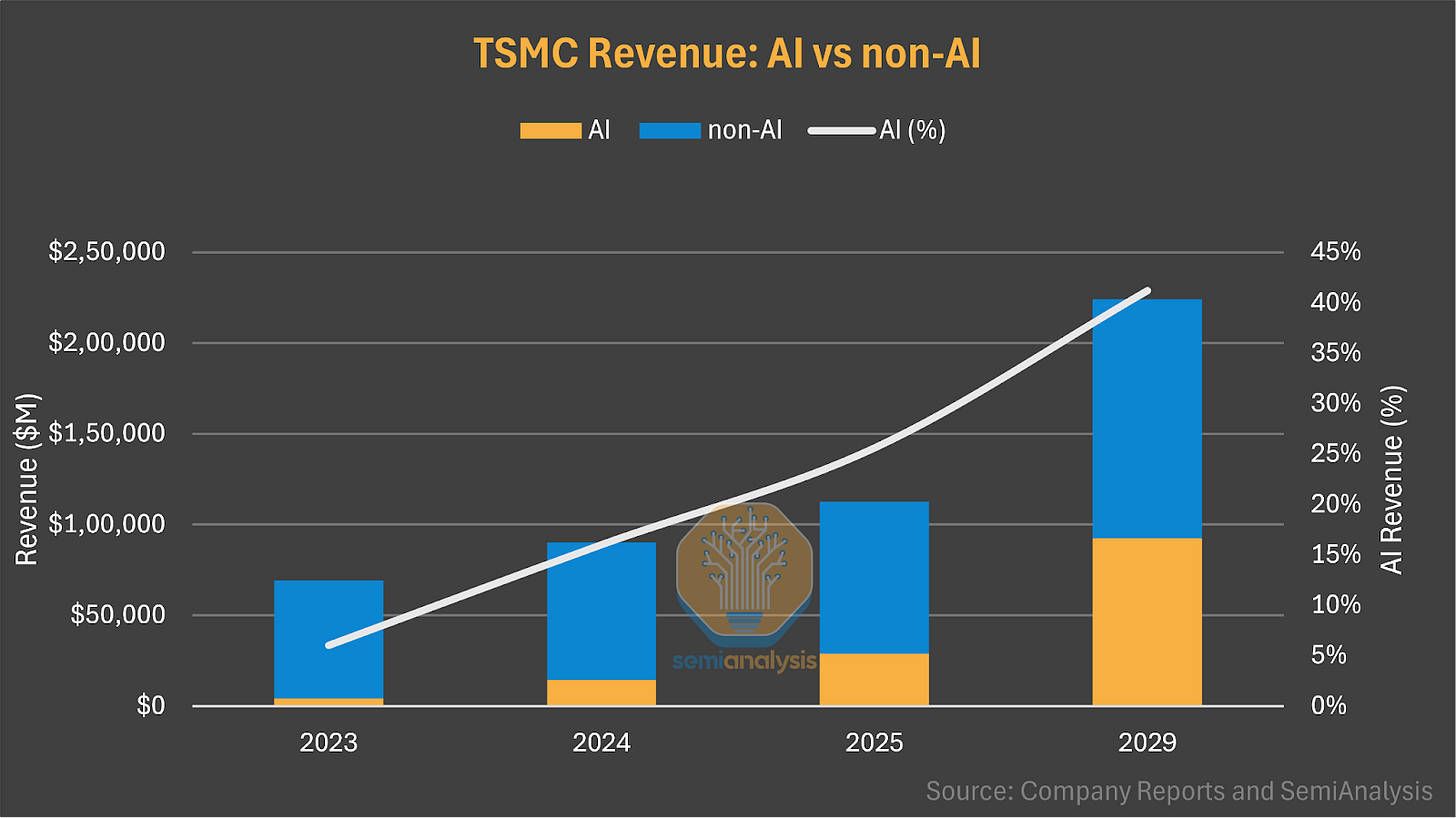

The most immediate driver for computing growth is AI workloads, primarily through Nvidia:

And the great Sravan Kundojjala modeled out what that growth could look like over the next 5 years, with AI approaching 40% of TSMC’s revenue in 2029:

With exposure to AI, edge devices, and seemingly every other major technology on the horizon (robotics, the metaverse, etc), TSMC has become an index on the future of technology.

As I said last year, and as I’ll be saying for many years: it’s never a good idea to bet against technology, and one I won’t be making any time soon.

As always, thanks for reading!

[You’ll notice I didn’t discuss geopolitical concerns. I have nothing unique or valuable to add to that conversation.]

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not investment advice and should not be used as such. Investors should do their own due diligence before investing in any securities discussed in this article. While I strive for accuracy, I can’t guarantee the accuracy or reliability of this information. This article is based on my opinions and should be considered as such, not a point of fact. Views expressed in posts and other content linked on this website or posted to social media and other platforms are my own and are not the views of Felicis Ventures Management Company, LLC.

How do you think about margins compressing as TSMC moves large amounts of production to the US where labour costs are far higher? If margins compress, earnings diminish and so too do valuations.

Do you view business operating model portability as a risk? I.e. can they replicate what they've done in Taiwan in the US, esp as it pertains to getting the proper talent (e.g. pick of Taiwan's best EE grads without competition from finance and software co's looking to hire)