Where do Tech Returns Come From?

An Analysis of 30 Years of Tech Returns, Value Accretion, Lessons, and What it Means Moving Forward

The next $100B company will not look like the last.

It feels like an obvious statement, but we can’t help ourselves from falling into pattern matching. Looking for the next Google/Meta/Amazon, or the Uber for X, the Airbnb for Y, the AI Agent for *literally any industry*.

Well, to not get swept up in the new trend every week, we’ve got to look back. Something akin to Churchill telling us,“The farther back you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.”

So I wanted to do an analysis of the largest companies founded in recent history. To not get caught up in narrative, but in what the data tell us, taking an outside view in the words of Mauboussin!

Causal thinking is a form of storytelling that comes naturally. It is a compelling way to anticipate the future and a convincing way to explain the past. Our minds are great at creating facile narratives to explain what happens in the world around us.

The second method is to think statistically, commonly referred to as the outside view. Rather than weaving a story based on causal links, the statistical approach examines what happened to an appropriate reference class of cases in the past. The results of the reference class are called base rates.

So this will be a deep dive on:

Data on value accretion in technology over the last 30 years

Lessons from that value accretion

What those lessons might tell us about investing in technology today

The TLDR:

The next $100B company will not look like the last

Know the game you’re playing: home runs, grand slams, or something more like Space Jam for Baseball (aiming for outer space)

Software is like chicken, 80% of it tastes the same

“Market size” may be the single greatest reason for great investors missing great companies

Companies resemble the technology waves they ride in on

Just because it would be irresponsible of me not to mention this, don’t underestimate the Power Law, ever.

Also, we published our Felicis Call for Startups last week. Do go check it out for the areas we’re excited to invest in.

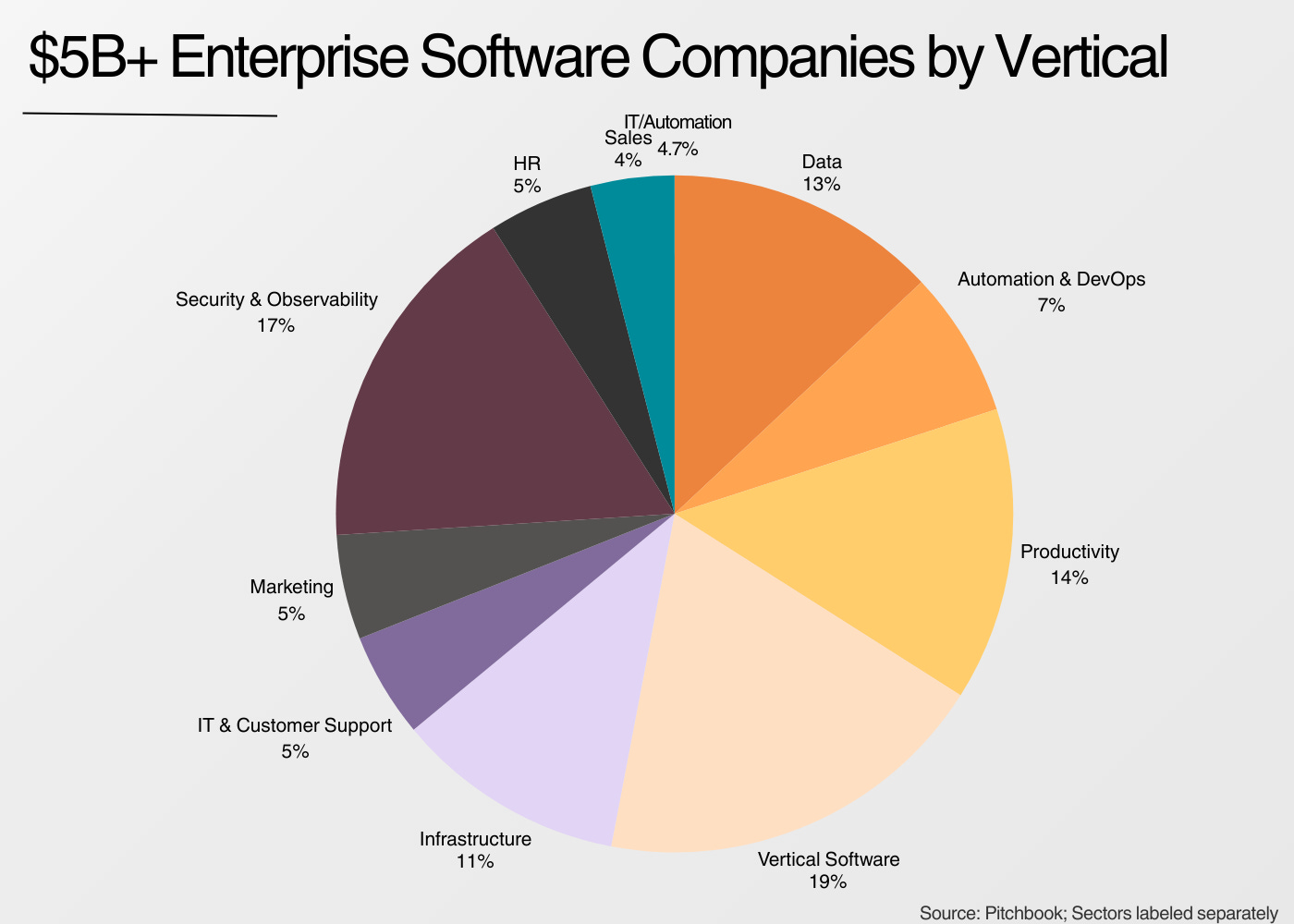

On Methodology: The vast majority of technology value has accrued to the largest companies, so I pulled all Pitchbook, IT-labeled companies worth $5B+, founded since 1995. (Note: this does exclude Amazon, Nvidia, Microsoft, and Apple.) I had Claude help categorize the companies, so do consider the exact data quite directionally accurate, and precisely inaccurate.

Let’s get to it.

Data on 30 Years of Technology Returns

The dataset includes $13T worth of value creation, 300+ companies, across 65 (!) categories. See the highlights of the most successful of those companies here:

Now I won’t belabor the Power Law anymore than I have to, but the top seven companies accounted for nearly 50% of this dataset.

Which leads to the first and most important takeaway:

1. The next $100B company will not look like the last.

First and foremost, the value of technology is driven by anomalous companies, founded by anomalous people. The very fact that they’re anomalous means pattern matching is more likely to make us miss the great companies than to catch them.

It’s hard to visualize a company’s path if it’s never happened before. How can you estimate the size of Google’s market in 1998? Or Meta’s in 2004? It’s impossible.

Take the current most anomalous AI company: OpenAI. It was founded as a non-profit research lab, without a clear technical vision, lost its cofounder, with a convoluted governance structure, and it’s on a path to be one of the most important companies in history. As anomalous as it gets.

There is no “public comp” for the most successful companies. They’re unique. The largest companies create categories, and that’s what makes them so hard to see.

Neil Mehta put it as looking for the “the very small number of the world’s founders who are going to produce a significant proportion of the value that humans enjoy.”

To start to get into the data, see the largest companies founded since ‘95:

The majority of these companies either created their industry or hugely expanded it in a way that they basically created their industry (Tesla for example).

Looking at the data by category leads us to the next takeaway:

2. Know the game you’re playing: home runs, grand slams, or something more like Space Jam for Baseball (aiming for outer space).

If we go back to Mauboussin’s idea of base rates, I’d argue we need a different mental model for investing in these various categories.

The majority of value has been created by consumer companies (dominated by the Power Law). However, nearly twice as many enterprise software companies were founded.

To visualize that, I added a column for ‘Slugging Ratio’, Value/Company, to get a sense of how Power Lawed different industries were:

Over the last 30 years, consumer companies have tended to be network-driven marketplaces with genuine winner-take-all dynamics. If you happen to invest in one of those giants, the only mistake tends to be underestimating how big they will become. Cue Yuri Milner’s investment in Facebook at $10B.

If a company can genuinely architect network effects into their business model, the upside is immediately increased.

Hardtech companies, any company building hardware, have the second highest ‘slugging ratio’, mostly because it’s harder to survive as a hardtech company. Typically, it requires more capital, takes longer to get to scale, is harder to build products, is potentially more exposed to fundraising challenges, and is harder to disrupt incumbents.

However, if they can get past that speed run, the market opportunities tend to be massive.

But there’s only room for a handful of consumer and HardTech companies. Because of that, enterprise software has become a perfect investment vehicle for an expanding venture capital landscape.

Businesses that scale rapidly, in non-winner-take-all markets, with strong moats, and low operating costs. In an environment with many venture funds, there are more winners to go after, more proven markets, and all-in-all much less risk. But plenty of upside if it does go right. A good recipe to derisk an inherently very risky industry.

3. Software is like chicken, 80% of it tastes the same.

I stole this line from Vista Equity Partners founder Robert Smith who said, “Software companies taste like chicken…They’re selling different products, but 80% of what they do is pretty much the same.”

If we look at the majority of the largest enterprise software companies, they’re either:

An application built on databases with unique workflows

Infrastructure to build those applications

Security to protect those applications

This isn’t to say these companies aren’t differentiated, but that their differentiation is much more nuanced than it seems on the surface. Sales, marketing, and building mindshare are all just as, if not more important, than technical differentiation.

In a world where software is getting easier and easier to build, features are replicated in days, and AI coding tools are getting better, technical moats in software may be confined to unique data or integrations.

The point is that technical differentiation tends not to be the defining variable of enterprise software companies.

In this context, I find the “GPT Wrapper” argument fascinating, stating that AI application companies are just rebundling LLMs. The majority of enterprise software companies are SQL (or NoSQL) databases, with unique workflows built for a specific set of customers.

If we look at the largest AI enterprise application companies recently, they’re “LLM wrappers.” But this is the exact same thing we saw over the last decade with the largest enterprise software companies, and they became $100B+ companies!

As I mentioned before, enterprise software is less risky and more predictable than other categories. Outside of horizontal enterprise software though, market sizing seems to be less of a constraint than it seems on the surface. “How big can this company become?” and “How big is this market?” are two very different questions.

4. “Market size” may be the single greatest reason for investors missing great companies.

If there’s one thing humans don’t handle well, it’s uncertainty. And that’s exactly what new markets introduce.

Palantir, Shopify, Uber, and many others, all (more or less) created new markets that didn’t exist before.

Even trying to add certainty to an inherently uncertain problem can lead to foolish behavior.

Take Aswath Damodaran and Bill Gurley’s infamous back and forth on valuing Uber. Gurley’s conclusion: Uber’s potential market could be 25 times higher than Damadoran’s original estimate.

I took a look at companies founded since 2010, with the highest multiple returns in public markets, an underestimation metric if you will.

A few patterns emerge:

Investors underestimated market size, especially for market expanders or vertical markets: Shopify, Guidewire, Zillow, AppFolio were underestimated. Similarly, in private markets, investors underestimated Toast, ServiceTitan, and other vertical software companies.

Companies had multiple-expansion tailwinds as new business models surpassed old: Tesla (the most extreme example) and (to a lesser extent) all the software companies listed saw a reframing of multiples compared to the incumbents they were competing against. Today, Tesla alone is worth nearly $1 trillion, more than twice what all of the big automakers were worth, combined, when it entered the market.

Investors underestimated the power of platforms: ServiceNow, Palo Alto, Crowdstrike, Workday, Atlassian, and Datadog all expanded their markets by expanding their product lines. As software became easier to build, it reduced the technical differentiation between platforms, making customers prefer platforms over point solutions. In times of consolidation, it’s good to be a platform!

This isn’t to say market size doesn’t matter, it’s to say: it’s really easy to get it wrong.

5. Companies resemble the technology waves they ride in on

If the last section was a “market sizing” section, this is a “why now?” section. The proverbial “why now?” question in venture asks: Why hasn’t this company been created before? What new revelation now allows this company to exist?

Most of the time, it’s a new technology wave that unlocks the ability for the business to exist. Today, it’s AI. Before, it was the internet, then mobile, then the convergence of internet and mobile, then the cloud.

We can see below when $5B+ companies were created by sector:

The internet connected the world, allowing the aggregator business model to emerge.

Mobile took it a step further, putting the internet in everyone’s hand, unlocking consumer marketplaces.

Fintech was a rare example of regulation unlocking a new technology industry, and saw a boon post-2010s Durbin Amendment.

The cloud was the most disruptive wave in the history of technology, unlocking the ability to build software with a credit card instead of a data center.

Now, with AI, what companies are unlocked and what will they look like?

AI coding tools take the cloud a step further, unlocking the ability for anyone to create software, not just developers. This will lead to a similar explosion of software that the cloud introduced.

It unlocks the ability to automate voice and text-based workflows. We’re already seeing this across coding, customer service, and AI scribing. But this will expand to many, many more applications.

This expands the market for software in ways we haven’t seen before. Just one example: in this dataset, there’s not a single legal software company valued at $5B+. Harvey, founded just three years ago, is already valued at $5B.

A good thought experiment on what we’re seeing with AI, from Rex Woodbury:

I liked Alfred Lin’s parallel between mobile and cloud. Back during mobile, a worthwhile exercise was to break apart features of the iPhone, then predict which companies each feature could enable. His example: the GPS allowed couriers to drive around with Google Maps, delivering food. This led to DoorDash.

There’s a narrow window for new companies unlocked by waves of technology, and we’re seeing that window of companies emerge right now.

6. So what comes next?

I was reading Will and Ariel Durant’s History last week, and came across this quote: History smiles at all attempts to force its flow into theoretical patterns or logical grooves; it plays havoc with our generalizations, breaks all our rules; history is baroque.

Perhaps this article is foolish to even attempt to fit the most anomaly-based industry out there into logical grooves!

What doesn’t change is human nature. If we solve by inversion, humans struggle to picture exponential growth, they struggle with anomalies, and they struggle with uncertainty.

To handle that uncertainty, our best bet is to:

Understand the “base rates” of company categories (what’s likely to happen)

Know where differentiation comes from (in software, sometimes it’s mostly sales and marketing)

View market size as a first-principles exercise on the problems to be solved instead of a pattern-matching activity

Understand that each wave of companies will be unique, it will be hard to predict, and that’s a good thing

Steve Jobs said of computers,”I think one of the things that really separates us from the high primates is that we’re tool builders…What a computer is to me is it’s the most remarkable tool that we’ve ever come up with, and it’s the equivalent of a bicycle for our minds.”

Steve was right. Computers unlocked a wave of creativity never before seen.

And now, we’re seeing the greatest bicycle for the mind ever created. What a time to be alive.

As always, thanks for reading!

Disclaimer #2: The information contained in this article is not investment advice and should not be used as such. Investors should do their own due diligence before investing in any securities discussed in this article. While I strive for accuracy, I can’t guarantee the accuracy or reliability of this information. This article is based on my opinions and should be considered as such, not a point of fact. Views expressed in posts and other content linked on this website or posted to social media and other platforms are my own and are not the views of Felicis Ventures Management Company, LLC.

Most people chase averages. You remind us to chase the rare signal.

Your piece isn’t about numbers alone. It’s about conviction, narrative courage, and founders who see volatility as a path to impact. You frame returns as rewards for discipline under uncertainty, not comfort.

MIT’s recent work on structural risk echoes this. Oxford’s new analysis on scale outcomes proves it again, concentrated bets reshape the field because they break the safety mindset.

You call us to think in arcs instead of points, to respect variance instead of managing it away.

Thank you for forcing us to ask what we’re really anchored to. Who is ready to bet on stories that change the system, not just fit into it?

Really enjoyed your article. This seemed to dovetail so well into my recent posts, I fashioned a separate one using your article (hope you don't mind). Thank you again for your invaluable contributions. https://open.substack.com/pub/alphadoc1/p/massive-multi-baggers-where-the-rubber?r=qlzxp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true