A Deep Dive on the Power Law

Data on VC returns in the last decade, public market returns in the last century, and what this means for investors.

Some principles in investing are so important that regardless of how frequently they’re discussed, they’re still under-practiced.

The Power Law is one of those principles.

The Power Law is the idea that a small number of participants create the vast majority of outcomes in a given system.

It’s most typically associated with technology and startups, but it extends past that. We can look at Warren Buffett’s annual letters for the clearest example; he alludes to it frequently:

In 2022, “The lesson for investors: The weeds wither away in significance as the flowers bloom. Over time, it takes just a few winners to work wonders. And, yes, it helps to start early and live into your 90s as well.”

In 2020, “Of course, some of our investees will disappoint, adding little, if anything, to the value of their company by retaining earnings. But others will over-deliver, a few spectacularly.”

Pick a few good companies and be patient enough to let them run.

As a thought experiment, we looked at what percentage of value is created by just the top 1% of exits (IPOs or acquisitions) in venture capital (specifically in the US, Europe, Australia, and Israel):

On average, the top 1% of exits create 32% of all value each year!

To clarify, this is the top 1% of exits! At the minimum, there were 200k venture-backed companies in the last decade, so only 2.5% of companies exited. That means, on average, .028% of companies created ⅓ of all exit value over the last decade.

Some context on how VCs make money: For those unfamiliar, venture capitalists collect funds by raising capital from individuals and institutions like pension funds and endowments and collecting a management fee from those groups. They then invest that money into startups and only see a return when those companies exit, typically through acquisitions or IPOs. They then distribute that money to their investors, and keep a percentage for their services. Exits are the lifeblood of the industry.

The rest of this article will be a deep dive into the Power Law and its importance for investors.

Venture Capital and the Power Law

We pulled data on the percentage of value accrued from the top 1% of venture capital exits (IPOs, acquisitions) in the last decade.

Of the ~5600 exits in the last decade (specifically in the US, Europe, Australia, and Israel), the top 1% account for ~40% of all value created. The largest outcome (Uber)? 2.6% of all venture returns at exit in the last decade.

We can see the percentile breakdown by year here:

Only 79 companies exited for $5B or more, and only 31 exited for more than $10B.

For those companies, the returns were the classic, incredible venture returns. Uber, for example, on a basic ROI calculation (not accounting for dilution), returned ~14000x for its investors.

Public Markets and the Power Law

In one of my favorite essays, Michael Mauboussin describes the lifecycle of industries and wealth creation throughout that process. In it, he references a study by Hendrik Bessembinder, where he studies decades’ worth of returns in public markets.

A quote from that Maouboussin paper:

[Bessembinder] found that about 16,500, or just under 60 percent of the sample, destroyed $9.1 trillion in value through December 2022. The other 11,600 or so, slightly more than 40 percent, created $64.2 trillion in value.

Of the net wealth creation of $55.1 trillion, more than $50 trillion was attributable to just 2 percent of the sample. The top 3 (½ of 1 percent of the 2 percent), Apple, Microsoft, and ExxonMobil, alone added almost $6 trillion.

I’ll repeat that again: 3 companies accounted for over 10% of all value creation in public markets throughout the duration of the study.

The Power Law doesn’t only drive private markets, it drives markets.

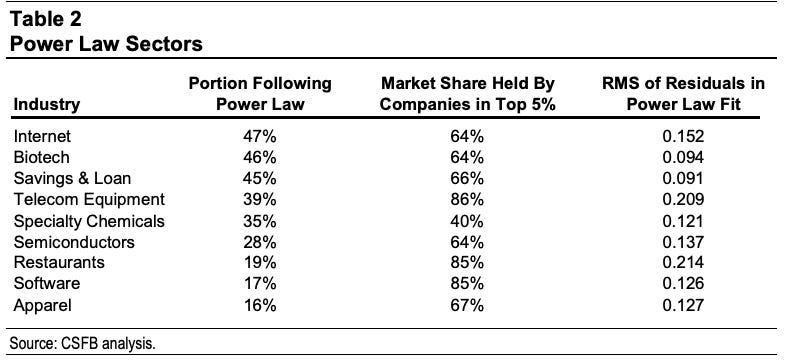

Important disclaimer: Not all industries follow a Power Law distribution. In a 2001 research paper by Mauboussin, he studied 18 industries and found that half displayed Power Law tendencies:

The other half didn’t for various reasons; some are regulated like utilities, some are services businesses that don’t scale well, and some are commodity businesses where there will be many players competing purely on cost.

What I can confidently say is that most technology industries are Power Law-driven, and the root of those can vary. Semiconductors are driven by their complexity, software’s driven by its rapid positive feedback loops, and network businesses by their network effects.

So we’ve established the clear existence of the Power Law, why does it happen?

Why does the Power Law Happen?

To answer that, we have to take a step back and look at the lifecycle of industries. Industries, at birth, see a rapid rush of companies entering the market. The industry creates a huge amount of value through rapid growth; after this point, most industries trend toward consolidation.

During the expansion phase of the industry, companies establish the characteristics that will eventually enable them to dominate the market. They find a way to best serve the needs of the market’s customers. We can see this in both the PC and the automobile industry:

So why do industries trend toward consolidation?

I would argue this is a law of nature, akin to natural selection. Companies compete for a limited amount of resources (customers AND investors).

If we compare this to natural selection, there are a limited number of resources that species compete for in a given area. Once a species has found resources, natural selection encourages the traits that allowed them to find and keep those resources, and those species specialize to maximize those resources.

It becomes increasingly hard for another species to compete for those resources because the original species has evolved to meet the needs of this environment specifically.

Back to companies, they develop the features customers want, generate earnings from that, and then invest those in more features. As they improve, it becomes increasingly challenging for competitors to offer the same service. Competitors must create a significantly better product, compete against a firm with increasing resources, AND convince existing customers to switch. Customers and investors then shift towards better service, further accelerating the consolidation.

These effects are compounding; as firms are competed away, it becomes harder and harder to unseat the incumbent.

The key point here is the idea of positive feedback: advantages compound.

Early winners get early customers and the initial mindshare of the industry, which leads to better funding, which leads to more customers, and so on.

Throughout this, the risk aversion tendency drives this compounding. Whether buying a product or financing a company, it’s less risky to pick the market leader. “You don’t get fired for buying IBM” is the perfect example.

Then, as the market consolidates, companies exit the industry and “donate value” to the established market winner.

Investors’ returns then follow the success of those select few Power Law winners.

If natural selection and consolidation are inevitable, then the better questions are:

When is the Power Law NOT in effect? (And what variables keep it from happening?)

How fast will industry consolidation occur?

To answer those questions, we can use technology and VC as a case study.

Why is the Power Law so pronounced in Venture Capital?

I’ll point to a few variables:

Winner-Take-Most Markets in Technology

Speed of Technology Consolidation

Faster Positive Feedback Loops

Higher Variance

If we have a winner-take-most market, then the Power Law is at play.

The limits to winner-take-most markets are bottlenecks on expansion like manufacturing speed, geographical preferences or regulations, and necessary in-person services. Some are regulated like utilities, some are services businesses that don’t scale well, and some are commodity businesses where there will be many players competing purely on cost.

With traditional physical products and services, you need to be in person, you need to manufacture goods, and you’ll slowly get feedback on those offerings. So, consolidation still likely occurs; it’s just much slower.

Technology, though, and software in particular, has essentially unlimited scalability and network effects. Feedback is immediate.

With lower switching costs and rapid growth, consolidation happens much faster. Which in turn, drives faster positive feedback loops mentioned above.

Finally, the higher variance of startup outcomes leads to higher dispersion in returns. Put simply, more startups fail, and more startups succeed magnificently.

Because VC invests mostly in tech, and tech evolves faster and consolidates faster, the Power Law is most immediately apparent here.

Put succinctly, startups are driven by speed. Technology changes faster, consolidates faster, and there are fewer limits on the growth of technology businesses. These are the types of people, industries, and technologies that move very fast.

What does this mean for investors?

Regardless of public or private markets, the mandate for outperformance is to be in the best companies.

We have two options:

We can either index, guaranteeing a piece of Power Law returns (this is why index funds work so well).

We can concentrate into select businesses with the hope that we have the ability to pick outlier businesses.

It’s not “Can I pick the upper half of businesses?”, it’s “Can I pick the top 10% or even the top 1%?”

In venture capital, Chris Dixon points out, “The home runs for good funds are around 20x, but the home runs for great funds are almost 70x.” As Bill Gurley says, “Venture capital is not even a home run business. It’s a grand slam business."

For example: Felicis’ top investment, Canva, 297xed from 2015 to 2024 ($165M -> $49B).

My final note is that the clear takeaway from the Power Law is a reminder that the path towards outperformance is being exposed to the very best companies, and there are fewer of those than we think.

Some things never change. 30 years ago, Warren Buffett said:

“You only have to have an opinion on a few things. In fact, I've told students if when they got out of school, they got a punch card with 20 punches on it, and that's all the investment decisions they got to make in their entire life, they would get very rich because they would think very hard about each one."

To that, I’ll end as his partner Charlie often would, “I have nothing to add.”

As always, thanks for reading!

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not investment advice and should not be used as such. Investors should do their own due diligence before investing in any securities discussed in this article. While I strive for accuracy, I can’t guarantee the accuracy or reliability of this information. This article is based on my opinions and should be considered as such, not a point of fact. Views expressed in posts and other content linked on this website or posted to social media and other platforms are my own and are not the views of Felicis Ventures Management Company, LLC.

Why don't services businesses scale as well? Wouldn't the margins for providing a service be similar to a lot of products

Hello there,

Huge Respect for your work!

New here. No huge reader base Yet.

But the work has waited long to be spoken.

Its truths have roots older than this platform.

My Sub-stack Purpose

To seed, build, and nurture timeless, intangible human capitals — such as resilience, trust, truth, evolution, fulfilment, quality, peace, patience, discipline, relationships and conviction — in order to elevate human judgment, deepen relationships, and restore sacred trusteeship and stewardship of long-term firm value across generations.

A refreshing take on our business world and capitalism.

A reflection on why today’s capital architectures—PE, VC, Hedge funds, SPAC, Alt funds, Rollups—mostly fail to build and nuture what time can trust.

“Built to Be Left.”

A quiet anatomy of extraction, abandonment, and the collapse of stewardship.

"Principal-Agent Risk is not a flaw in the system.

It is the system’s operating principle”

Experience first. Return if it speaks to you.

- The Silent Treasury

https://tinyurl.com/48m97w5e