Open Source Business Models: Notes on Profiting from Free Software

How open source companies have historically captured value, commoditizing your complement, and value creation vs value capture.

“The barrier to entry is very low. The barrier to excellence is very high.” - Neil Mehta on Venture Capital (Repurposed by Eric Flaningam, Referring to Software Businesses Today)

Admittedly, I wanted this article to be a follow-up to my last piece on Free Software. MY GOAL was to learn lessons from the original “free software” companies (i.e., those monetizing open source).

However, after studying the most successful open-source businesses of the last few decades, I want to be honest that the takeaways aren’t as neat and tidy as “playbooks on building open source companies.”

In reality, open source is a wonderful strategy to solve the cold start problem in infrastructure companies: getting people to try it. But getting people to pay for it is very hard. And then protecting that value from competitors is even harder.

So, I’m sharing my notes on the big question in open source: Open source creates so much value for the world, but how can companies best capture that value?

Two disclaimers: I’m biased towards open source businesses, I think they’re good for technology, and I think they’re a great zero-to-one mechanism for building a tech business. Secondly, I’ll be discussing generalized observations in this article. Anomalous outcomes from anomalous companies, so the best companies likely defy the generalized observations I’ll make here.

I. How Have Open Source Companies Historically Captured Value?

Open source software, software developed and given to the world for free, has risen in importance and adoption for the last several decades. The godfather Bill Gurley started writing about it over 25 years ago.

Ever since IBM unbundled hardware and software back in 1970, there’s been an ideological movement around open source (see “Why Software Should be Free” from one of the pioneers of open source). Proponents of “free software” had the belief that distributing it as widely as possible moves technology forward as fast as possible.

But there’s a misalignment with this belief: the best way to make change in a capitalist society is to align financial incentives. For forty years now, companies have been trying to figure out how to align those financial incentives.

Many have done so very successfully (none more so than Databricks, who just raised at a $100B valuation).

The core premise of modern open source businesses is this:

Developers lead software adoption in the enterprise, which creates a cold start problem:

You need developers to bring software into the enterprise, but you need the enterprise to buy software for the developers.

Open source solves that by getting developers to use free software, and creating a wonderful market mechanism in the process.

This is why open source is so dominant in databases and developer tooling.

But by giving away open source for “free”, it makes it much harder to eventually charge for features. “Why should I pay for a tool I can get for free?”

But the reality is that (1) enterprises have unique needs because of the complexity of their deployment and the security necessary for a successful deployment, so (2) the cost of open source is not free.

To solve for that, most open source companies give away a core product that can be used by anyone, but will charge for additional enterprise features (security, advanced features, cloud hosting) and/or services (helping customers deploy software).

However, the core problem is building sustainable technical differentiation, so eventually open source companies keep more and more of their features behind a “paywall.”

And honestly, this has been the monetization method for the majority of open source companies!

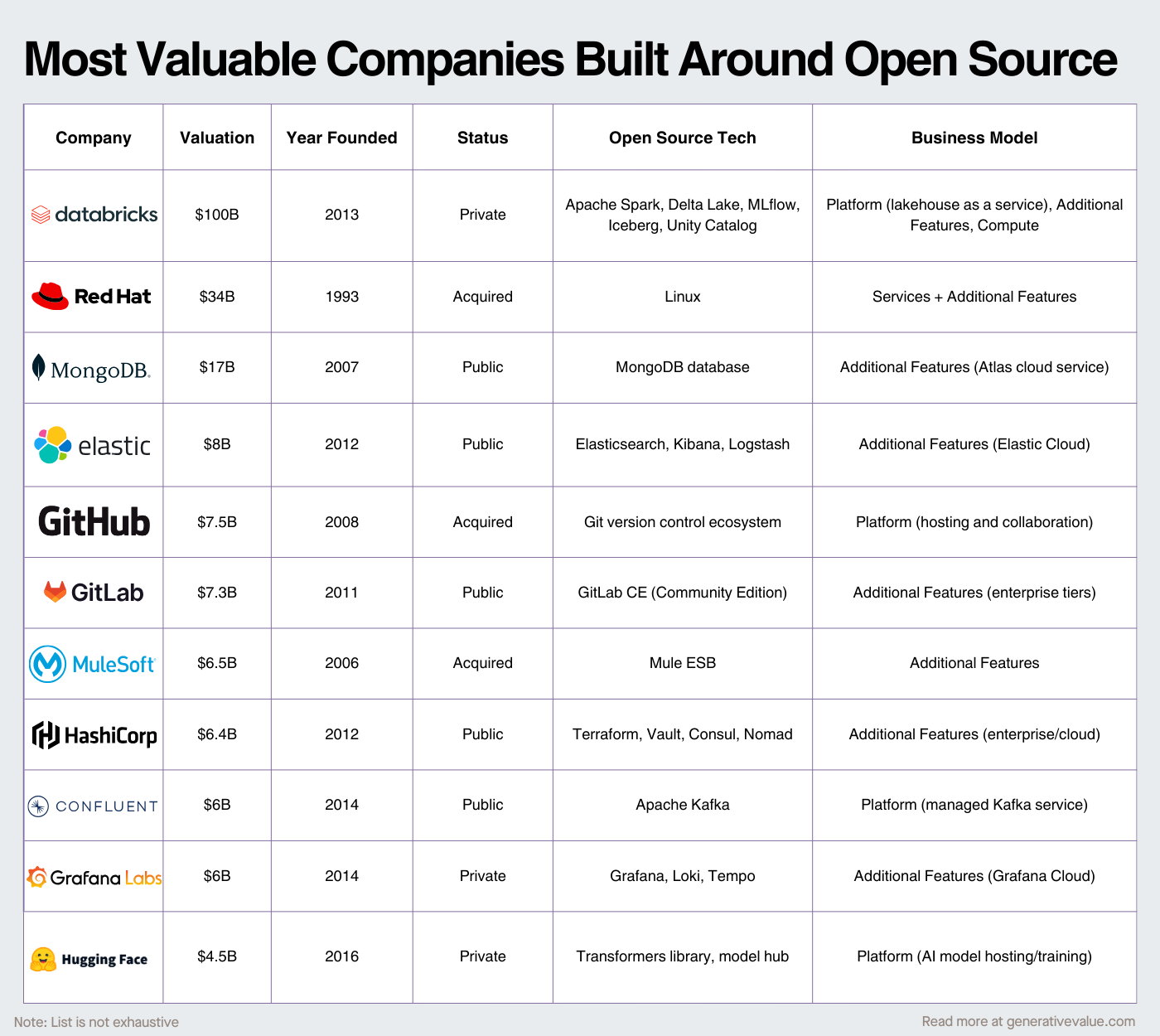

Charge for either services, additional features, compute costs & hosting, or a platform. And to spare you 1500 words on the history of open source (and yes, that was draft #1), I’ll just highlight a few of the companies who helped pioneer those business models:

Redhat and Linux: Offer services (customer support, manual updates) to enterprises who had complex needs

GitHub and Git: Offer hosting services and use network effects as a moat

MongoDB and…MongoDB: Use a free database as a marketing funnel to close enterprise clients who need additional features (Security & Authentication, Operations & Management, Performance & Scaling, High Availability & Disaster Recovery, Compliance & Governance). Confluent, Elastic, and others would follow a very similar playbook.

Databricks and Spark: Offer a platform of open source technologies (Spark, Unity Catalog, Iceberg, MLFlow, Delta Lake), and charge for the convenience and performance of the enterprise offering. Databricks would develop more and more features in the Databricks platform to create differentiation.

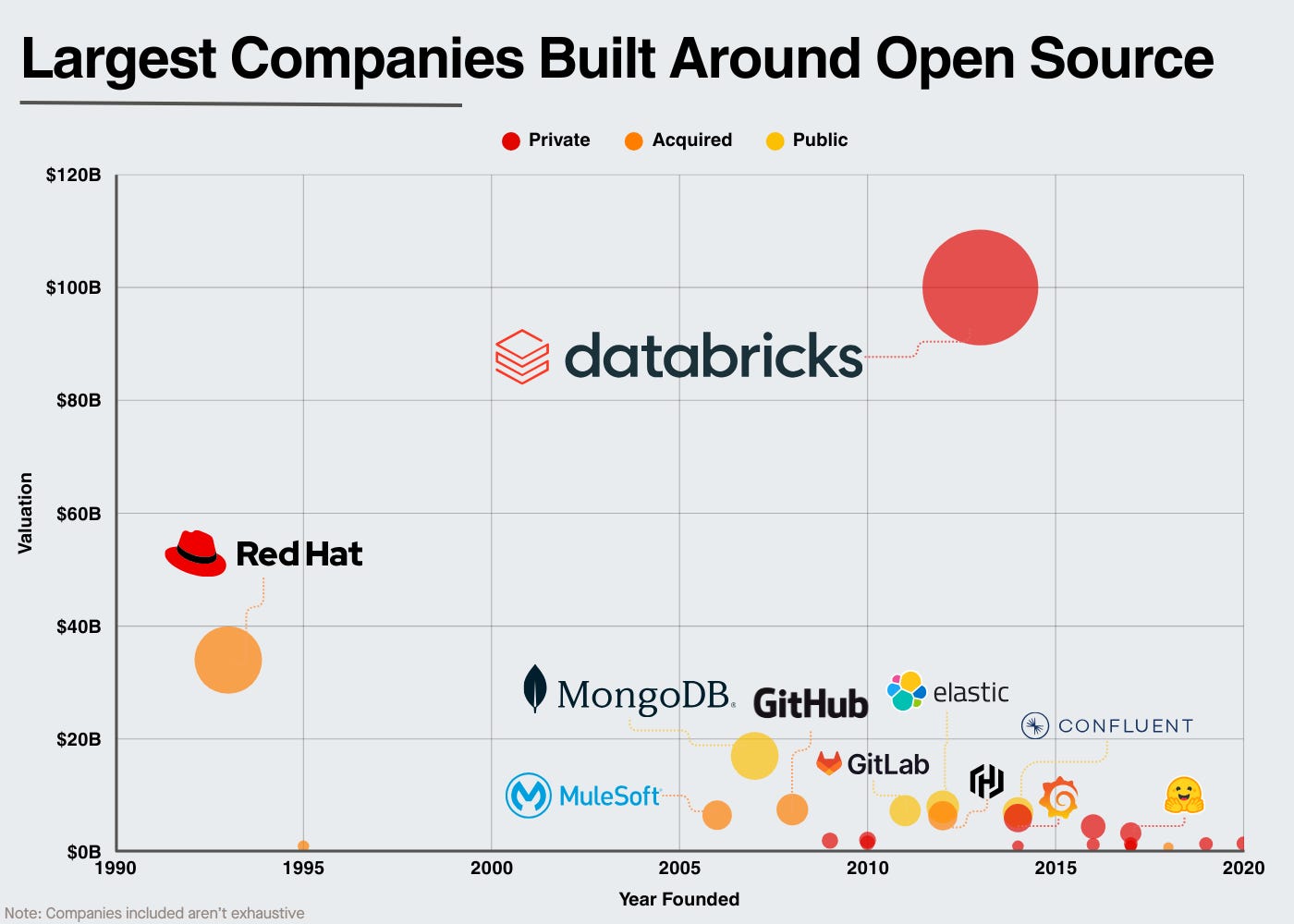

Here are many of the others that have been successful:

Examples of Most Successful Open Source Companies and How they Monetized

All of them solved some core problem FIRST and monetized after (and most said it was brutally challenging to do so). Then they added on additional features, and the most successful created network effects or platforms in addition to those features. But it’s never been easy.

The challenges of monetizing open source:

Ali Ghodsi summarized the challenge of open source best:

“I sort of liken it to playing baseball and having a strategy that you’re going to hit two home runs in a row after each other consecutively. The first home run is going to be your open source home run. You’re going to give away the software, and it better be a home run. “Home run” here is defined as the whole world loves it and downloads it, otherwise you’ve accomplished nothing, you’ve just given away your intellectual property for free and accomplished absolutely zero. So that’s home run number one…Then you need to hit another home run in Peter Thiel’s parlance another Zero to One that’s 10x better than the open source project.”

So this tells the abridged history of open source business models:

Open source is almost a necessity in developer tooling and data infrastructure.

It provides both wonderful marketing and a great feedback loop.

But it requires an incredible technical team in order to release the amount of quality features to solve customer problems and marketing team in order to get people to pay for the tool

The challenges of protecting open source value:

And finally, protecting that tool from competitors is not easy. We’ve seen every major open source company put out some defense against the hyperscalers. Many have done so through licensing and adding additional features.

MongoDB is a great example. It was originally released under the GNU Affero General Public License (AGPL). But this didn’t prevent companies like AWS from taking that software and releasing their own version of software. So in 2018, MongoDB re-released their database under the SSPL license, which prevented other companies from re-distributing for commercial purposes.

This was largely in response to the hyperscalers offering competitive products using MongoDB’s technology. And it’s brutal to compete with the hyperscalers because they can offer that product (in theory) for free and just make their profits on the compute costs.

The second path, the one that Databricks has most successfully pursued, is just building more and more features. Ali Ghodsi talked about their initial pivot into this here:

So at Databricks we had Spark and the cloud vendors were just giving it away and beating us to it, so we had to come up with something that’s 10x better, so we came up with something called the Photon engine, which is a complete rewrite of the engine under the hood.

So then the value proposition would be, “Hey, you already love Spark, you’re already using Spark, I’m getting the cost of it down to a tenth, and we can split the difference”. The initial reaction of people would be, “Well, wait a minute, that’s not open and you’re not giving away for free anymore”, and it’s like, “Yeah, but we need to make money somehow”, and they said, “Okay, if you can prove to me that you really can lower the cost by that much, I’ll split the difference with you”. That became the strategy, but we only came up with it in hindsight.

Important note: this requires an incredible technical team that can continue to innovate faster than anyone else in the market.

The ability for the hyperscalers to release a competitive product at a lower cost and profit from compute costs points to another observation: many of the most successful applications of open source have come from their strategic value, NOT from charging for an open source product.

II. Open Source as a Strategic Tool

So open source is hard to monetize, but why did Databricks acquire Tabular for $1B+? Why is Meta open-sourcing Llama? Why is OpenAI open-sourcing their trailing-edge models?

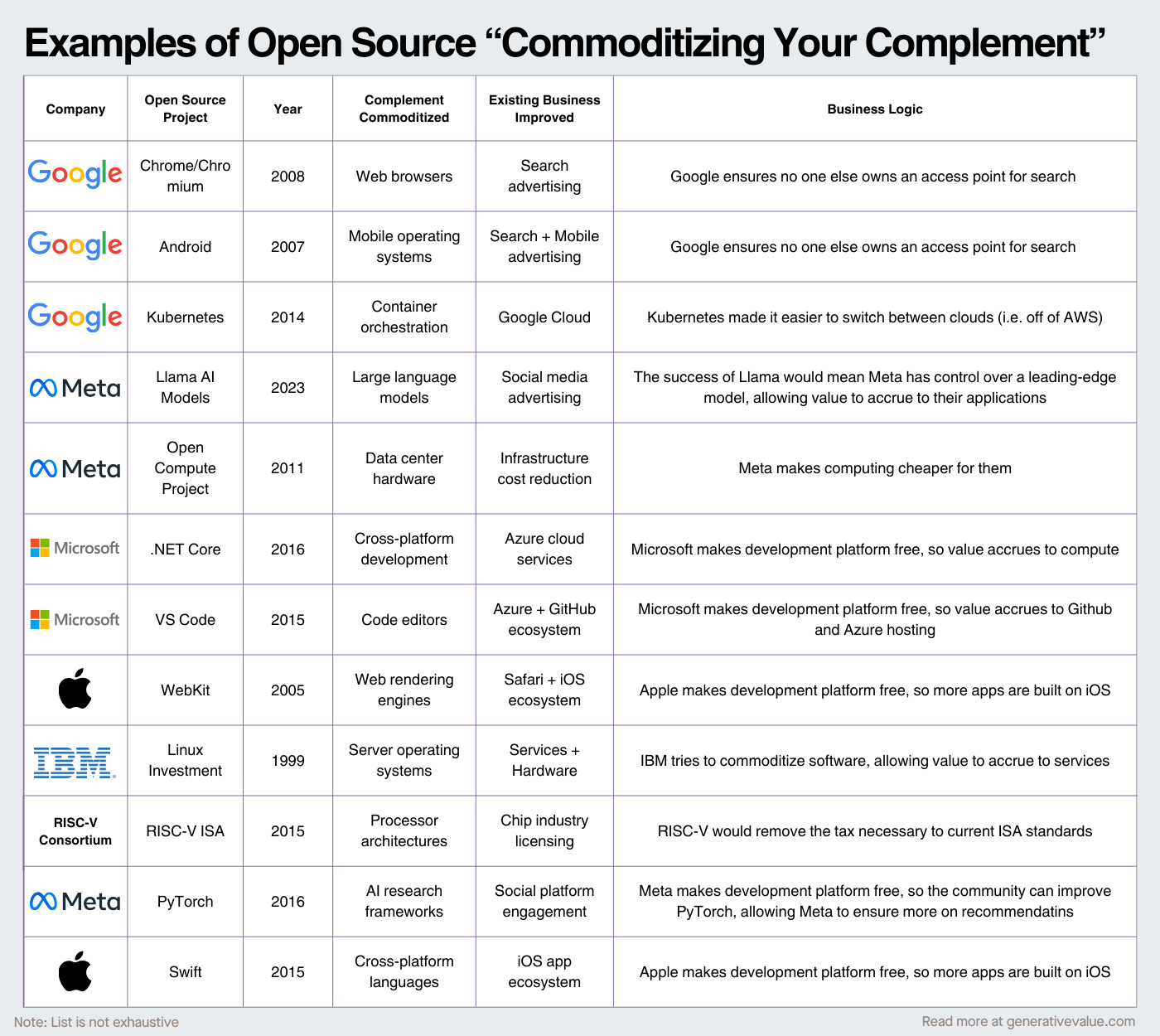

Because FAR more value has been created from using open source as a strategic weapon than an offensive. This ‘commoditize your complement’ strategy is straightforward: if you can commoditize one piece of the value chain, value will flow to another. And open-source is a wonderful commoditizer (it’s literally giving away software for free).

In many of these cases, a big tech company has a dominant core business that no other business line can compete with. So it makes far more sense to open-source a product that protects the core business than trying to charge for it.

Google’s been the mastermind behind many of these:

Acquiring Android to ensure they don’t lose a key access point to search

Open-sourcing Chromium to ensure they don’t lose a key access point to search

Open-sourcing Kubernetes to make it easier to switch off of AWS

And this ‘commoditize your complement’ strategy is the primary one we’re seeing today with Open Source AI.

AI & Open Source Today

So the lessons from open source are: open source is an amazing marketing tool, it's a great way to get customer feedback, getting people to pay for it is really hard, and it's a great way to commoditize your complement.

Just a few examples:

Why would Meta spend billions on Llama without charging for it?

Meta just wants control over a leading-edge model. They have the monetization engine and the distribution to profit from leading-edge models. However, if they are completely reliant on another model, then value could accrue to that vendor instead of Meta’s distribution.

By open-sourcing Llama, they're hoping no single competitor can establish a monopoly over AI models while protecting their core social media and advertising businesses.

Why is Nvidia investing so much in software?

Clearly CUDA gets a lot of attention. But Nvidia continues to develop open-source AI software infrastructure from models (Isaac Groot, Cosmos) to Agent Frameworks (Agent Intelligence toolkit, NeMo). Again, the logic is that Nvidia will never earn as much on software as they do on hardware, but by giving away software for free, they can lock in developers to their hardware.

Commoditize your complement.

Why did OpenAI open source their model?

Two-fold. First, open source is great for marketing, and OpenAI is seeing around corners for the unrest that closed-source AI could bring. By open-sourcing their trailing-edge models, they get ahead of that.

Secondly though, OpenAI is monetizing primarily through the application layer, the clearest complement to foundation models. So, in theory, they can survive and thrive without charging for their APIs (this won’t happen in the near term, just a theoretical point).

III. Value Creation vs Value Capture

This debate is not a new one to anyone in the open source community. Open source is a strategy that’s been successful at what it’s good for: getting developer-first businesses from zero to one, gaining mindshare, and strategically commoditizing pieces of a value chain.

We continue to see new successful companies built around open source (take Felicis investments n8n and Supabase for example). And we continue to see successful attempts at commoditizing complements.

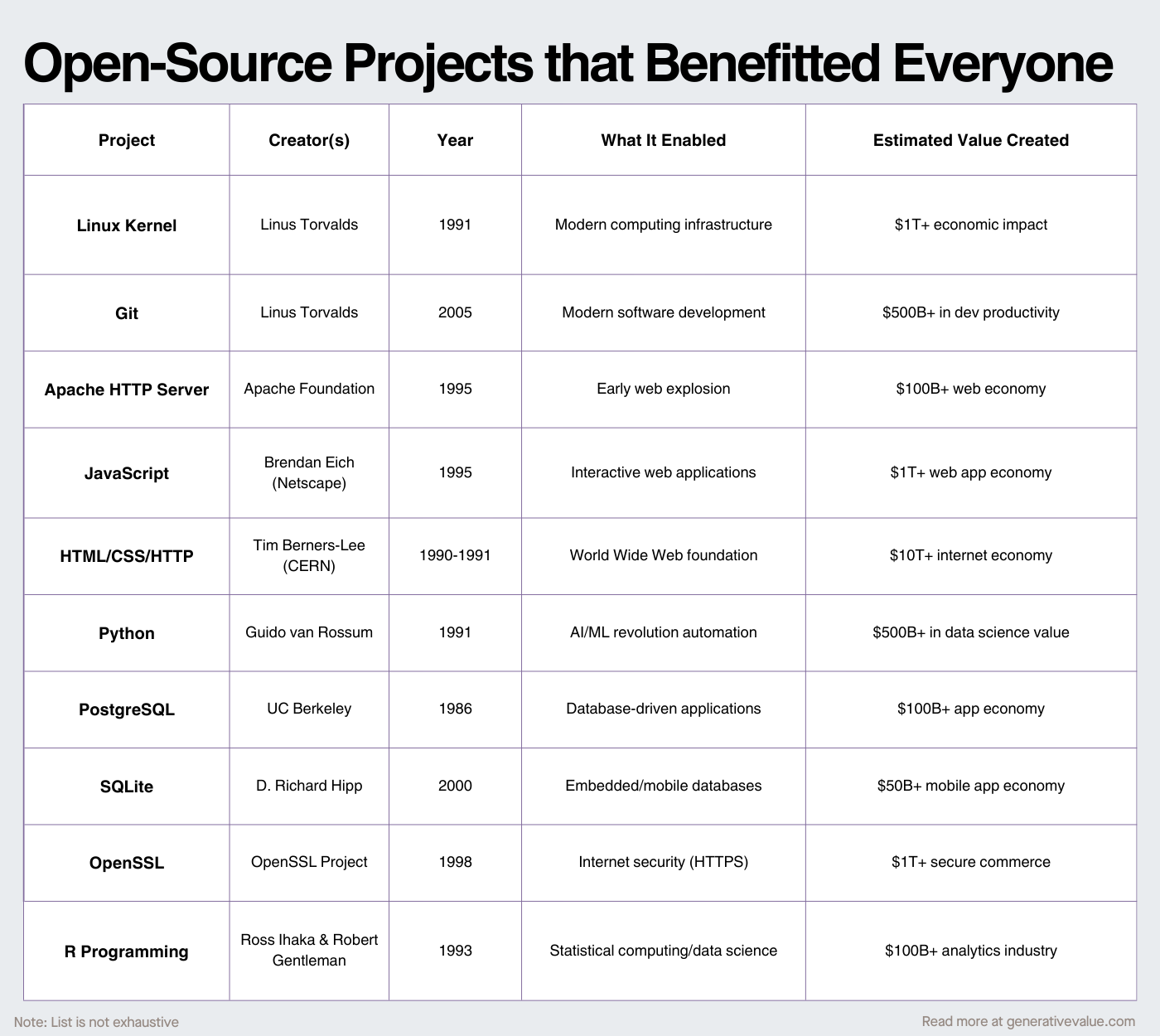

While all that is true, far more value has been created from open source than captured. Many open source projects didn’t benefit anyone; they benefited everyone.

For the open source community, there’s no good answer here, which is why this article ended up being more of a “notes” vs “analysis” article. So I’ll make a few predictions:

As the barrier to entry to software decreases, open source will continue to become more prevalent, but it will be harder to charge for. Queue the need for innovative business models.

The strategic value of open source companies will continue to outpace the discount of future cash flows.

Many open source companies are worth far more strategically than the value they’ll create from cash flows, because they’re such effective complements to a platform. See Databricks’ $1B+ acquisition of Tabular, for example.

We will see an increased rate of open source acquisitions for two reasons:

First, the strategic value of open source I talked about above

Second, the bottleneck for so many top tech companies today is AI talent. And there are many incredible technologists building in open source.

And to end on a positive analogy, I write this newsletter because (1) I love investing and (2) I love the process of creating something useful.

There’s a reason I don’t charge for the newsletter. And it’s the exact same reasons why developers open source a lot of their code, they just like doing it.

This was the ideological roots of free software: plant a seed today, so there's shade for people tomorrow. And it's worked incredibly well. Technology today is built on open source.

And the reason I love business models is that if you can figure out how to align incentives, you can figure out how to make the changes to make things better.

Incentives run the world, and I'd like nothing more than more great open source businesses to be built.

If you’re building one of them and agree/disagree with what I said, feel free to reach out.

As always, thanks for reading!

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not investment advice and should not be used as such. Investors should do their own due diligence before investing in any securities discussed in this article. While I strive for accuracy, I can’t guarantee the accuracy or reliability of this information. This article is based on my opinions and should be considered as such, not a point of fact. Views expressed in posts and other content linked on this website or posted to social media and other platforms are my own and are not the views of Felicis Ventures Management Company, LLC.

> "far more value has been created from open source than captured. Many open source projects didn’t benefit anyone; they benefited everyone."

Great point. If you follow this line of thinking, it suggests that the way to have invested around the open source theme over the past few decades wasn't to pick a basket of open source companies, but rather just to buy VOO or QQQ. The value that didn't stay in the open source companies leaked into every other enterprise in the developed world.

Maybe we will see something similar in LLMs -- if the value from AI mostly leaks out as broad based surplus, then maybe we should sit out most venture deals in AI apps and instead just buy the S&P 500.