Q4 ‘25 Cloud Update (What’s going on with software?)

And what does it mean for the hyperscalers?

Given that they’re at the center of the tech ecosystem, I write a quarterly update on the hyperscalers (Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and kind of Meta). For the last few quarters, this commentary has focused primarily on CapEx investments (which won’t be neglected in this update).

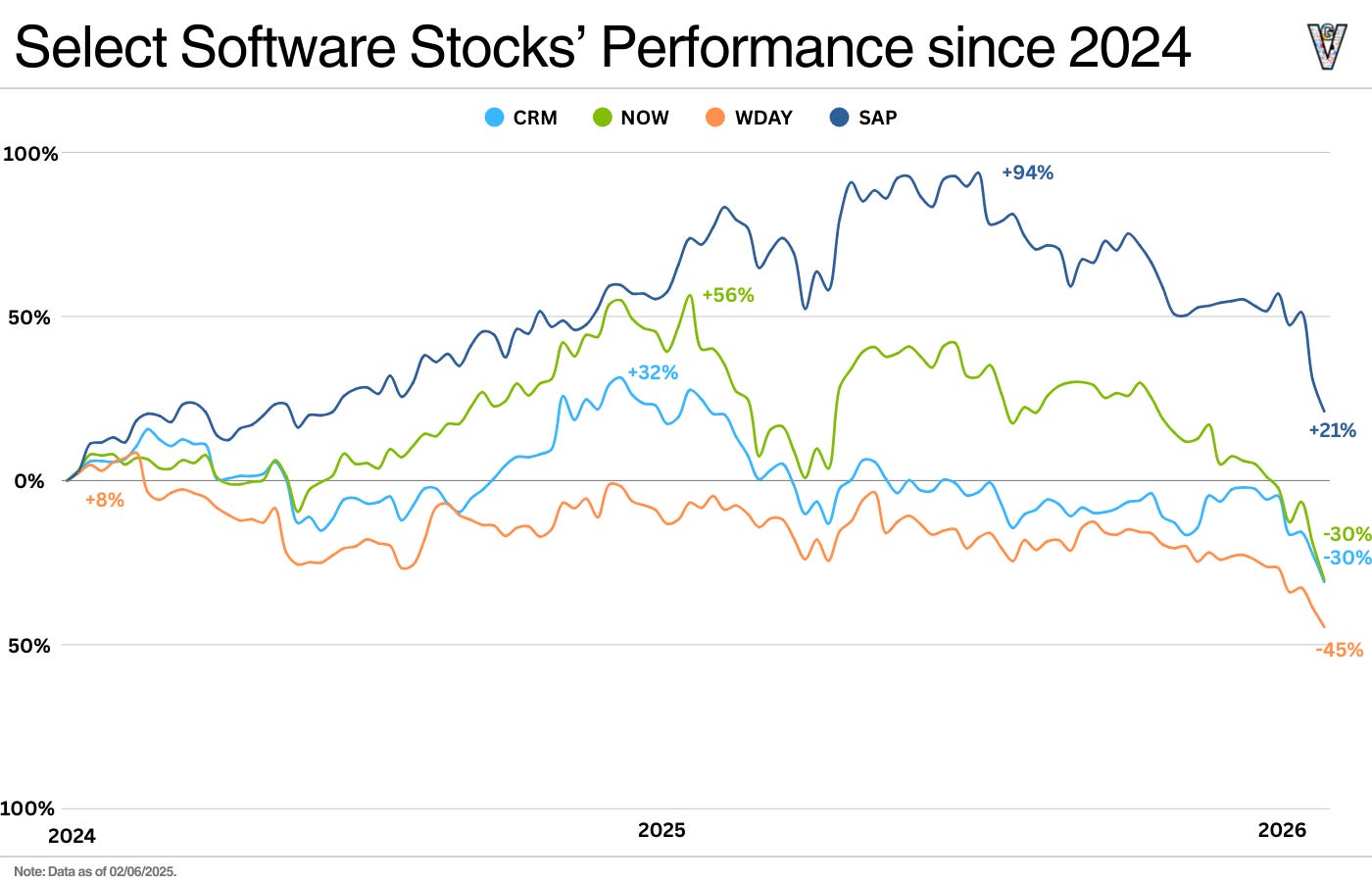

BUT the last quarter has been one of the worst quarters in the history of software stocks (note: I didn’t say businesses). So it feels like there’s no other place to start.

1. What’s going on with software?

Software just had one of its worst months ever. Let me show you a graph with the stock performance of the canonical “system of record” software companies over the last two years:

But the fundamentals (revenue growth, margins, retention) haven’t materially changed in these companies.

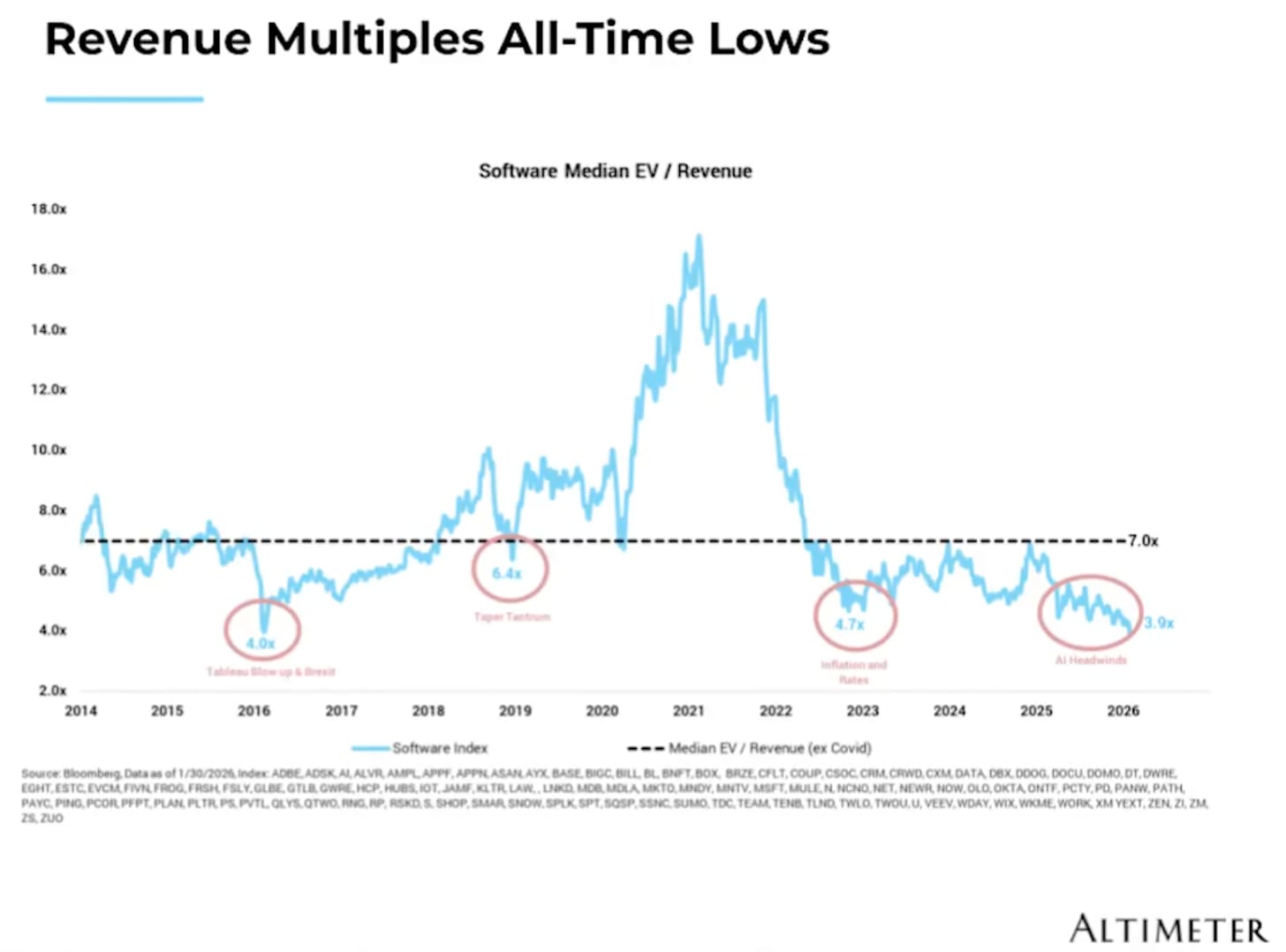

So to be clear: this “software armageddon” is about the resetting of expectations on the future of software business models, not about the “death of software”. This resetting of expectations has led to software’s lowest multiples of the last decade:

This multiple compression has come primarily from two factors:

The narrative of “software as the perfect business model” led to very high multiples

The high gross margins, operating leverage, switching costs, and growth of software businesses led many to the idea that “enterprise software is the perfect business model.” Which, in turn, led to very high revenue multiples on these stocks. But this narrative ultimately overestimated the market size and competitive differentiation for many software businesses.

The perceived competitive advantage of software has decreased dramatically with the rise of AI coding tools

I wrote an essay last year on where I thought software business models were trending over the next decade. In short, as software becomes easier to build, software companies would have a lower competitive advantage, causing an increasing amount of value to accrue elsewhere in the value chain.

And I want to reiterate this point now: software is the hardest it will ever be to build today. If you play out the improvement of these models over a 5-10 year period, the cost to build software will continue to decrease dramatically.

This combination of high initial expectations and a clear catalyst to change those expectations has led to the “collapse” of software stocks.

2. So is software dead?

But in that same essay, I also tried to make the point that doesn’t mean “software is dead.”

Let me elaborate on that now. The beauty of enterprise software business models is twofold:

High operative leverage: write code once, sell it infinite times (with incremental costs for customer service, R&D, maintenance, sales costs, etc)

High switching costs: It is a hassle to move off of software, especially “systems of record” for large enterprises

On the latter point, I’ve been in many, many meetings with customers of large software products (Microsoft, ServiceNow, Databricks, Workday, SAP, etc), and it takes A LOT to get them interested in moving off these platforms. These can be multi-year migrations, which tend to be very painful. And more importantly, if they fail, it’s the project lead’s career on the line.

There’s a popular adage that enterprise software is like an annuity (once you sell it once, you get to collect that revenue for decades). As far as I can tell, for the large system of records, that’s still intact.

The challenge is where does growth come from going forward?

What the rise of AI coding tools means for incumbent software companies is that each new dollar of revenue has to beat out two competitors:

A product providing the same service (albeit likely with less functionality) but is much cheaper (given it was much cheaper to build with AI)

An AI product that provides a fundamentally different service than the incumbent software solution (who will try to build an AI product as well)

That’s a tough battle to fight! And there’s historical precedent here. Consistent with the history of technology, it’s often not that the revenue of the old technology shrivels up, but that its growth is eaten up by the new technology.

So in summary: High initial expectations + the fear of AI coding tools killing software’s competitive advantage led to the collapse of software multiples. But the switching costs of large enterprise software tools mean most of the existing revenue base will be safe, at least for a while. The question is where growth will come from going forward, and the answer is not clear.

But given the topic of this article, what does this mean for the hyperscalers?

3. What does this mean for the hyperscalers?

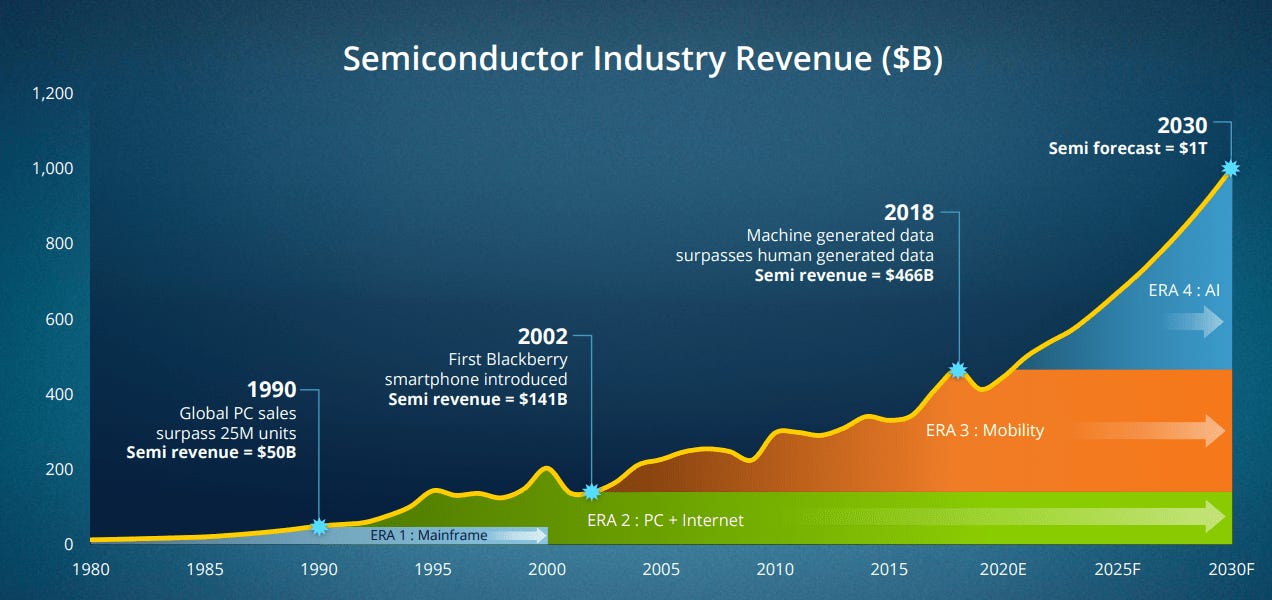

The AI infrastructure buildout and the hyperscaler CapEx funding it have been the biggest news in tech over the last few years.

This “death of software” question helps explain why hyperscalers are spending so much to fund their AI buildouts. The logic goes like this:

Risk of disruption (stick)

Many of the hyperscalers’ largest customers (outside of the AI labs) are large software companies.

The hyperscalers themselves are among the largest software companies in the world.

This means that if AI does indeed start to capture revenue that was previously going to enterprise software applications, the hyperscalers must capture a piece of that revenue to maintain their exposure to the future of enterprise technology.

The amount of compute necessary to fund this expansion is nearly unfathomable (carrot)

Outside of the semiconductor ecosystem, the hyperscalers are the clearest and most immediate beneficiaries of AI.

Microsoft reported that it has roughly $300B in RPO (contracted revenue) from OpenAI.

Presumably (though not confirmed), the resurgence in growth for AWS and GCP is coming from contracts with large AI labs.

Combined, these companies have ~$400B in cash and marketable securities on their balance sheets and generate $100B in net income per quarter (no reasonable alternative investment).

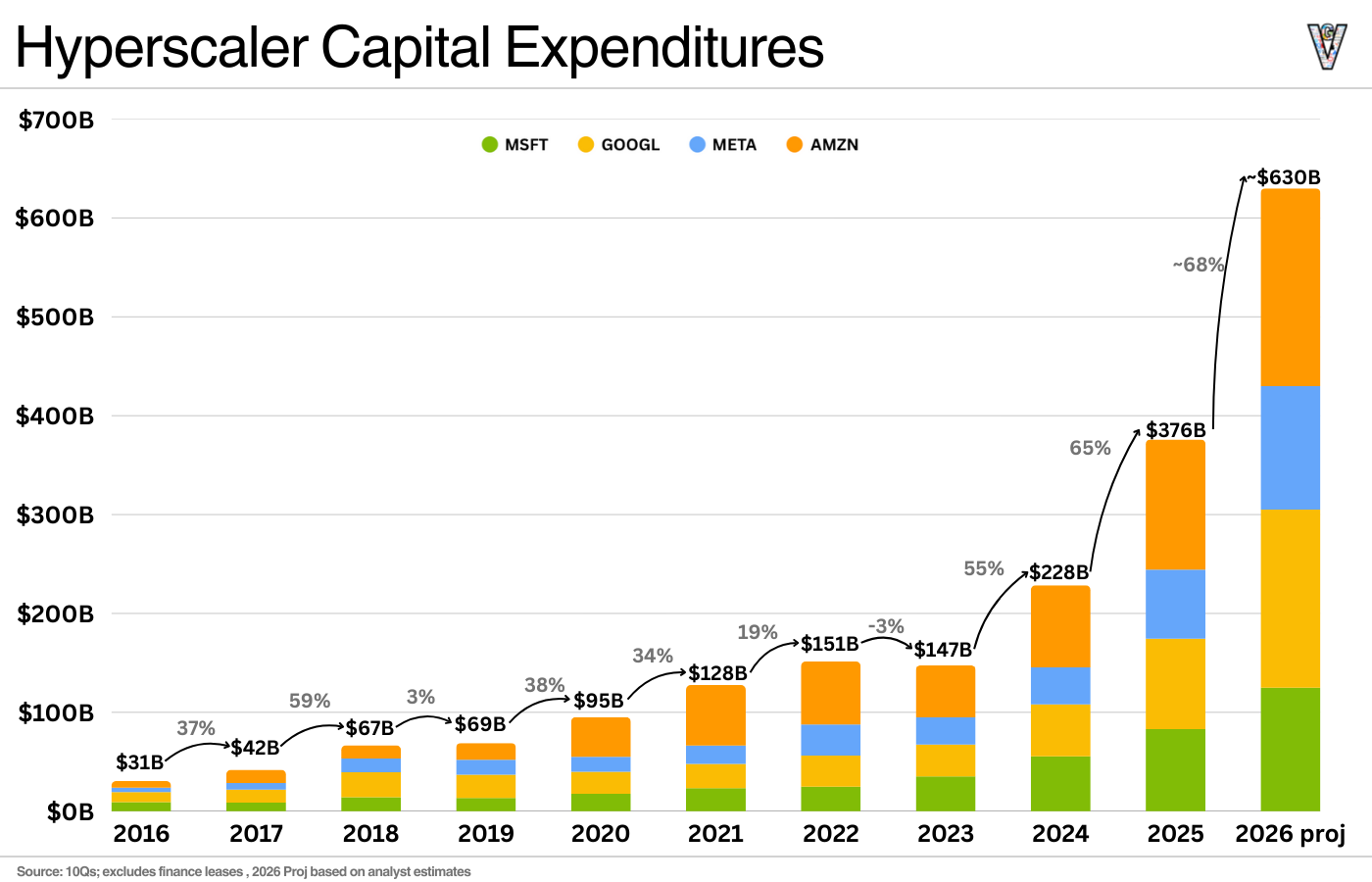

This risk of disruption (stick) + immediate revenue opportunity (carrot) + no reasonable alternative for investment continues to lead to staggering investment numbers!

4. This dynamic is leading to a staggering amount of CapEx in 2026 (and over the short term, will be the largest driver of market share changes)

If we look at announced numbers and analyst projections, these four companies are expected to invest roughly $630B in Capital Expenditures next year:

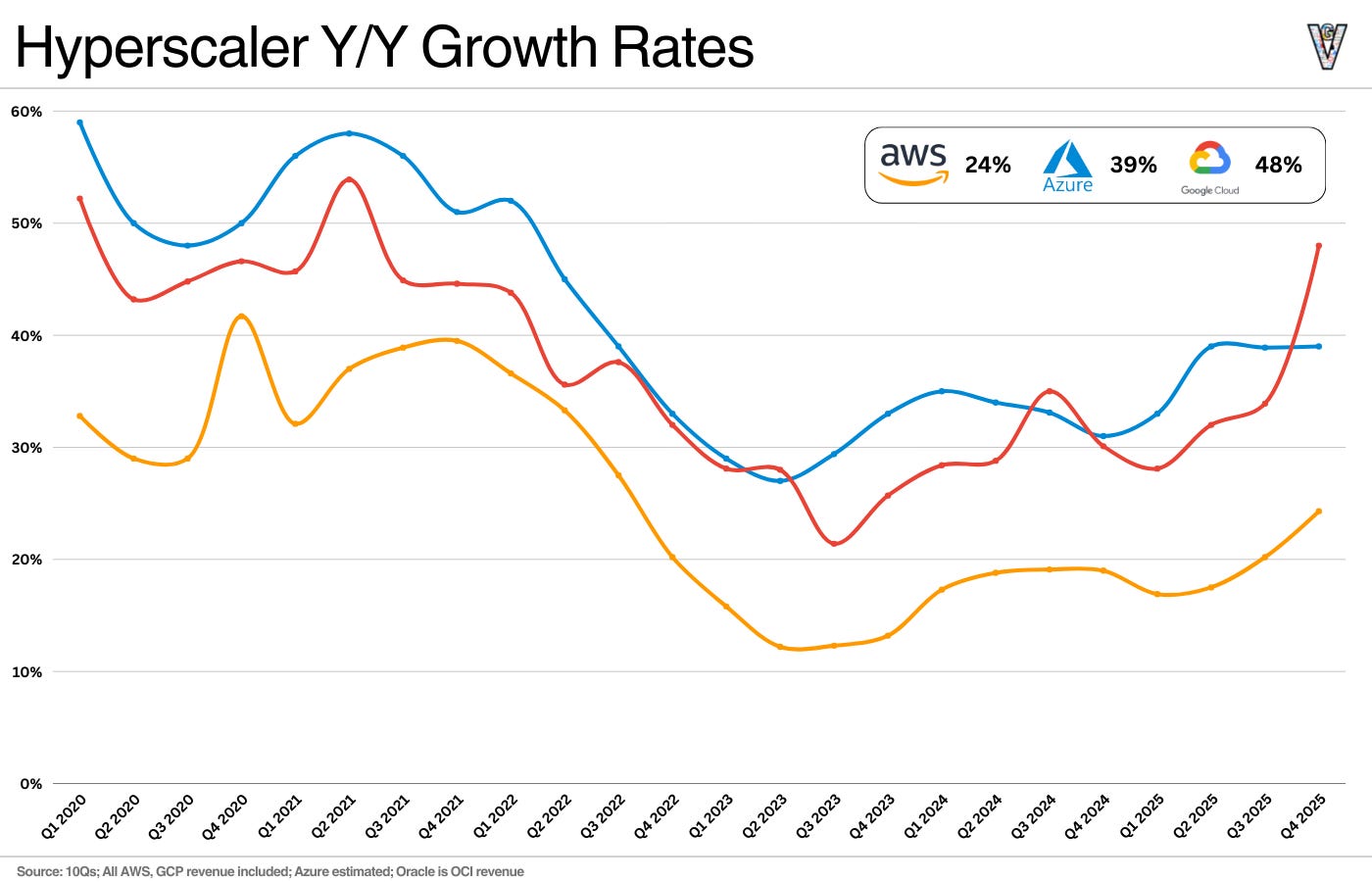

Given the immediate revenue opportunity from funding model training and application inference, this will be the biggest driver of market share changes for the foreseeable future. See the growth rates of these cloud companies below:

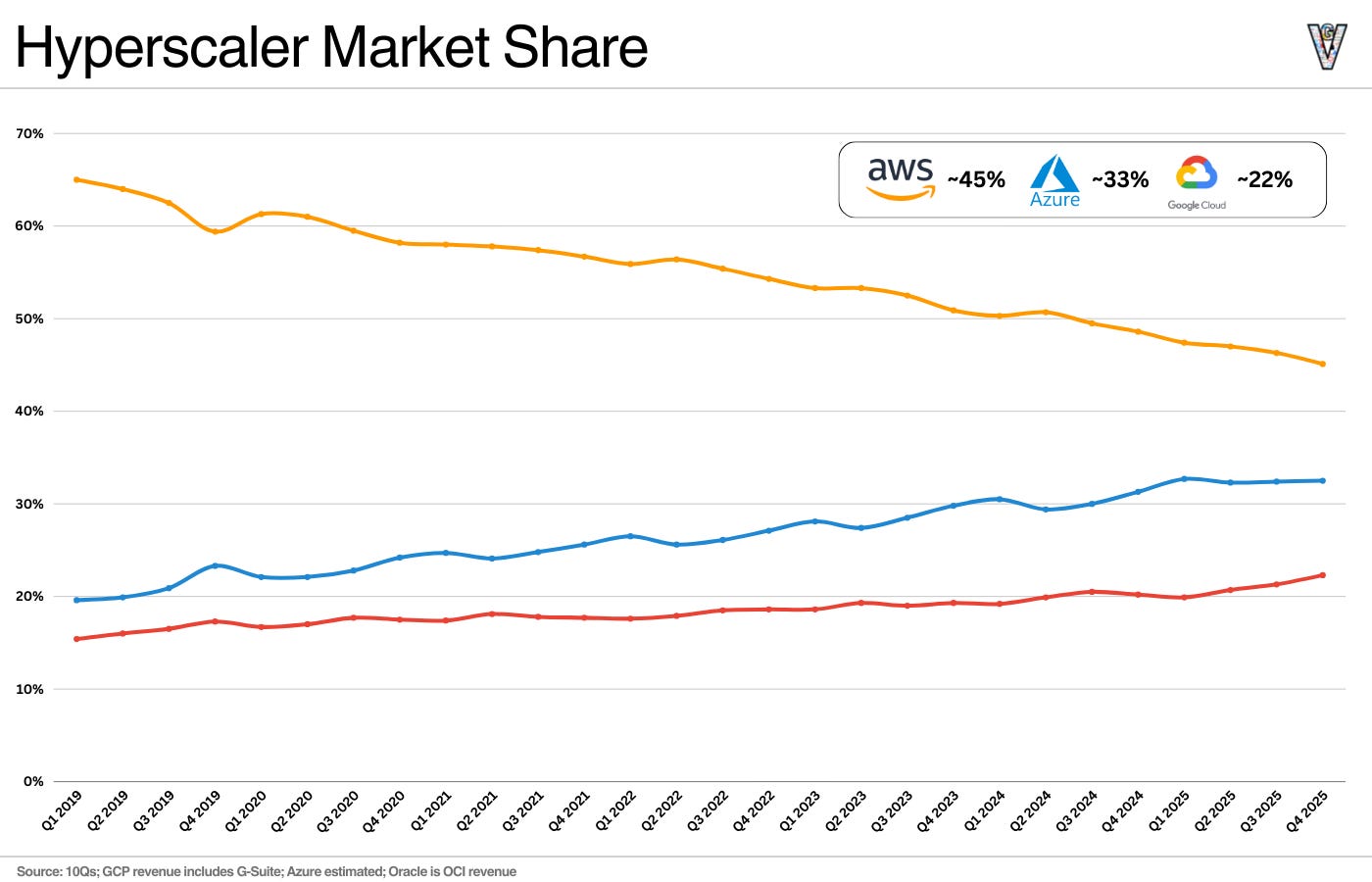

For companies with this much revenue (a combined $320B in revenue run rate), these growth rates are just incredible. We can see the updated estimated market share here between the three large cloud providers:

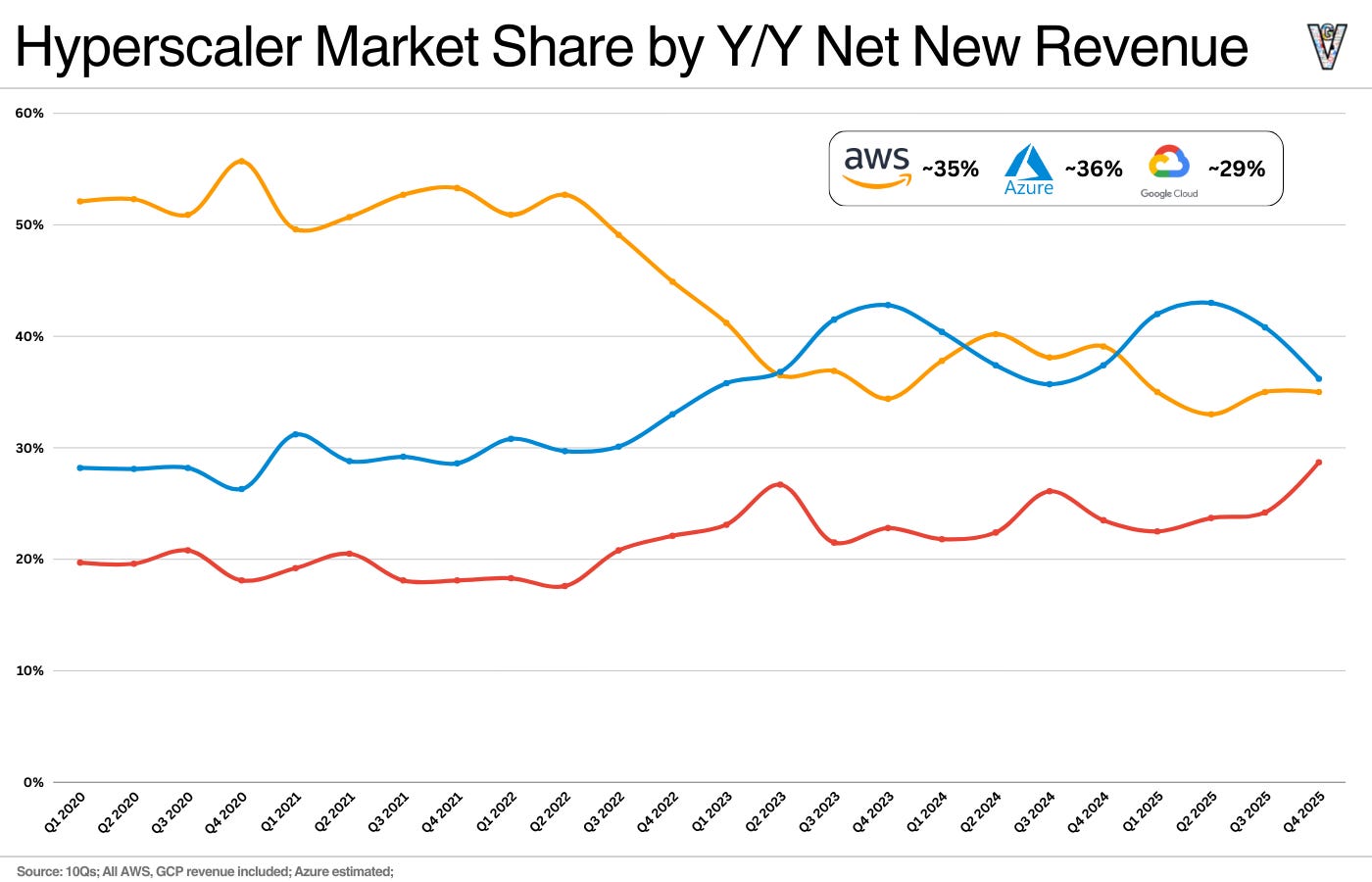

The more interesting metric, though, is market share “momentum”, or net new revenue generated Y/Y. In short, what % of NEW revenue generated over the last four quarters did each cloud company generate?

Again, AWS and GCP had especially strong quarters.

5. One Final Note on Competitive Advantage Periods

In times of technology booms, it’s easy to get caught in the short-term results.

One of my favorite investing papers is Competitive Advantage Period: The Neglected Value Driver by Michael Mauboussin. In summary, moats are discussed frequently in investing. But the durability of moats is equally important.

The question at the crux of this moment in software is about durability. The software multiple collapse is really just investors saying: these moats won’t last as long as we thought. For hyperscalers, the strategy right now is to extend the duration of their competitive advantage as long as possible.

I’m not foolish enough to predict how this plays out, but it’ll be fascinating to see how much clarity (or lack thereof) we have by next quarter. Til then!

As always, thanks for reading!

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not investment advice and should not be used as such. Investors should do their own due diligence before investing in any securities discussed in this article. While I strive for accuracy, I can’t guarantee the accuracy or reliability of this information. This article is based on my opinions and should be considered as such, not a point of fact. Views expressed in posts and other content linked on this website or posted to social media and other platforms are my own and are not the views of Felicis Ventures Management Company, LLC.

Great article! Curious to see how these software titans monetize agents and convert to token economics. I can see a world where license count remains the same and these software behemoths then take on additional modules/features that will be so productive that their customers will purchase the modules with the same users and productivity, as a result, will explode. I think this scenario makes total sense under the themes of 'AI will not take away jobs, it will create more' and 'productivity continues to increase, not just efficiency'.

I continue to question the logic of whether falling costs to produce software will lead to reduced competitive advantage to incumbent software firms. Software production costs (cost to deliver a unit of functionality) have fallen by orders of magnitude over the past several decades. Over that period, enterprise customer preference for 3rd party SaaS tools over in-house development has gone up and up, and the software winners are bigger than they have ever been. This is despite the prevalence of free open source alternatives in every category imaginable. If we believe in the power of AI coding agents and assistants, why is it bad for software firms for the productivity of their largest cost center to go up by 3-5x?