Free Software & The Future of Software Business Models

How do you build sustainable business models in the age of AI-generated code?

Outside of ChatGPT/Claude, coding has been AI’s killer use case. AI has made software development far cheaper and easier, and that trend will only continue.

This rise has been well-publicized, but it feels to me like people leave the argument at “software is dead.” I want to lay out the second piece of the argument: “software is dead, long live software.”

So I’m writing this post to answer the question: What business models benefit from this trend, and how can companies build business models that take advantage of AI-generated software?

I’ll start with historical precedent.

Free Software

January 1st, 1970: IBM created the modern software industry by unbundling hardware, software, and services. For the first time, a major computing company sold software as a standalone product, creating the model the industry would follow for the next 50 years.

20 years prior, GE “sold” early versions of commercial software. More precisely, they bundled them and gave them away for “free” in order to sell their CNC machines.

It was a means of differentiation, a sales pitch. “Buy our hardware, and you get our software and services for free.”

Software was free, and it was a differentiator.

With the rise of AI coding tools like Cursor, Claude Code, Lovable, we’re entering a world where software business models look more like those of the 1950s then the 2010s.

The TLDR of my argument today is this:

Software is getting cheaper and easier to build, and that will only continue.

Because of that, technical differentiation will be harder to create and maintain.

That doesn’t mean software isn’t valuable; it’s highly valuable, but customers will be less willing to pay for software alone.

So, software development looks increasingly commoditized, meaning value will need to be created elsewhere.

Because of this, “free software” will be more common, and that will necessitate sustainable business models built around free software.

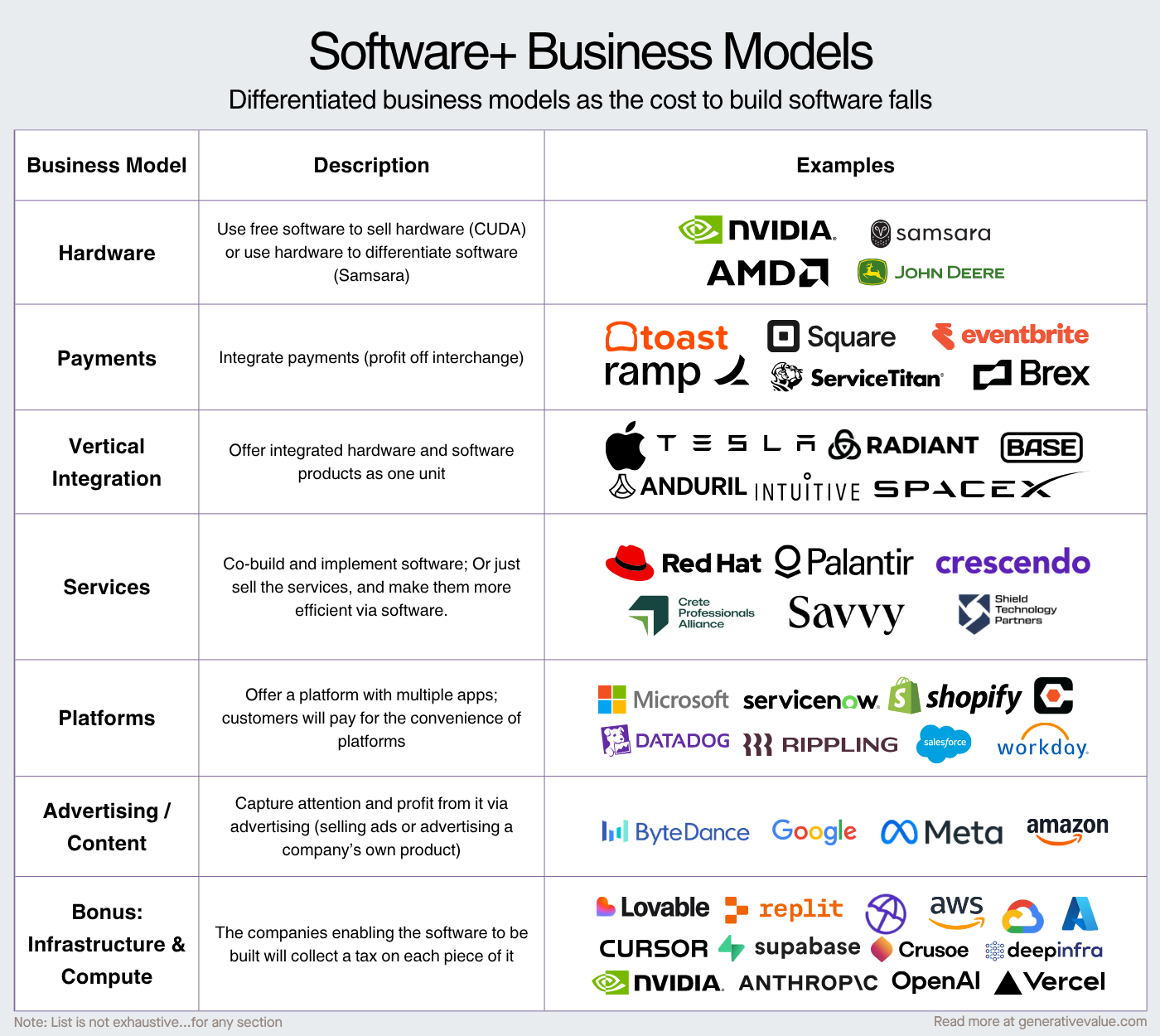

Those business models include:

Hardware: Use software to sell hardware (or vice versa)

Vertical Integration: Offer vertically integrated hardware and software

Services: Charge for the work itself (accounting, legal) or offer services to integrate software into complex, custom deployments

Platforms: Customers will pay for the convenience of platforms, not the functionality of point solutions

Payments: Give away software, charge for interchange fees

Software as Advertising: Software essentially becomes “interactive content.” (∞) bonus points if network effects are involved

Infrastructure / Compute: The platforms that enable “free software” will collect their tax on each piece of it

Disclaimers: Not all of these examples are “free software”, but all are examples of differentiated business models. Software switching costs are incredible; in an alternate universe, this article would be called “searching for switching costs.” Once software’s in place, it tends to be very hard to displace. If there’s an opportunity to rapidly scale software in a new market (like new markets created by AI), it’s wise to cement switching costs as fast as possible. Also, there are many moats to be created outside of these business models. Fault-tolerance matters. Vertical software and regulatory requirements create moats. This is not an all-encompassing article, rather a trend that will play out over the next decade, and my thoughts on how to position yourself so it’s a tailwind rather than a headwind.

Let’s get to it.

1. Use Software to Differentiate Hardware (or Vice Versa)

The clearest beneficiary of free software today is hardware companies. In the past, it was tough to be great at both hardware and software. That barrier to entry is changing.

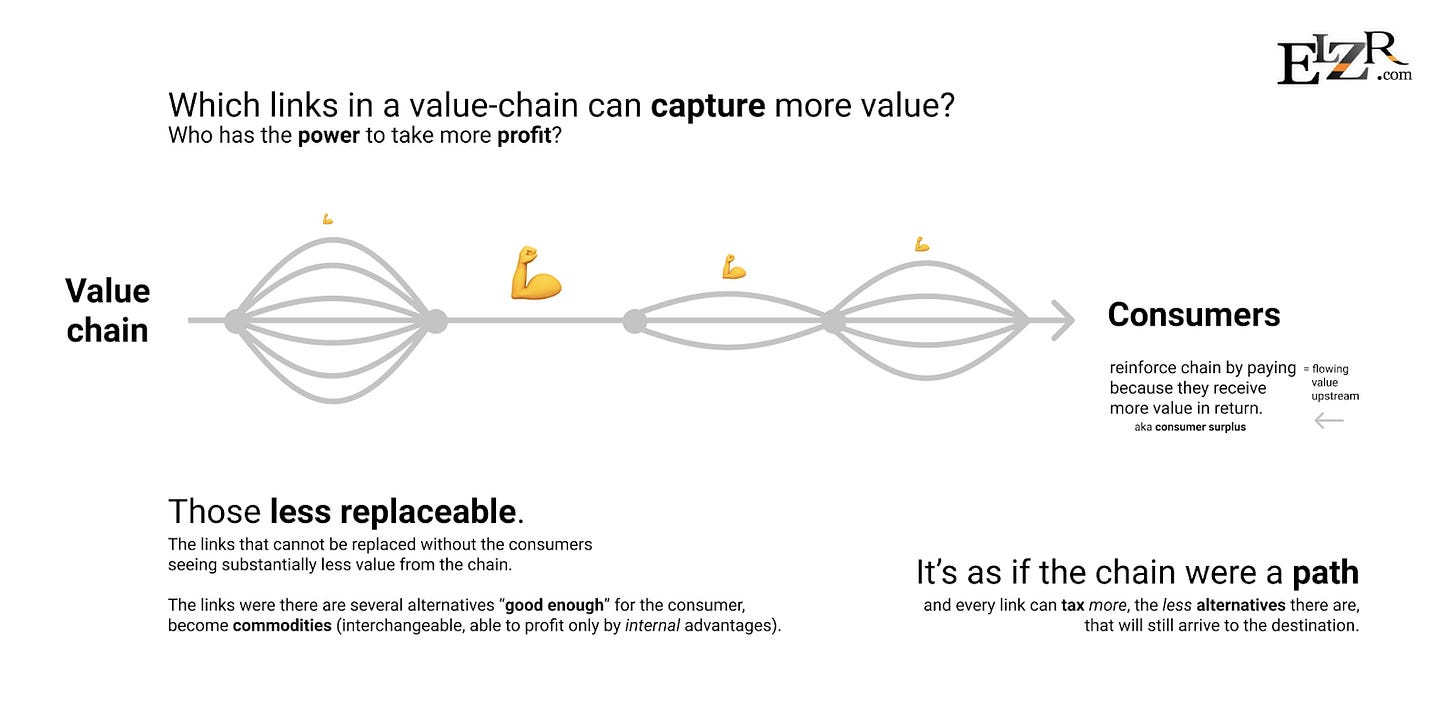

The core idea of commoditizing your complement is that as prices decrease in one part of the value chain, they increase in another.

If we take a simplistic view of the computing industry, the two primary components of the value chain are hardware and software. If software accrues less value, value flows to hardware.

To take advantage of this, companies can either give away software for free to differentiate their hardware (for example, Google open-sourced Kubernetes to make it easier to switch off of AWS). OR use hardware to differentiate software; if you can sell hardware upfront, you can collect the joys of switching costs.

It helps this argument that the most valuable “free software” in the world, managed by an individual company, is Nvidia’s CUDA.

Since the early 2000s, they’ve been developing the toolkits to “accelerate computing” via CUDA’s programming language, libraries, and drivers.

Today, it is the biggest differentiator for Nvidia’s hardware platform. See this quote from Semianalysis’ analysis on AMD’s MI300X vs Nvidia’s H100/H200:

In short, when comparing Nvidia’s GPUs to AMD’s MI300X, we found that the potential on paper advantage of the MI300X was not realized due to a lack within AMD public release software stack and the lack of testing from AMD.

AMD’s software experience is riddled with bugs rendering out of the box training with AMD is impossible. We were hopeful that AMD could emerge as a strong competitor to NVIDIA in training workloads, but, as of today, this is unfortunately not the case. The CUDA moat has yet to be crossed by AMD due to AMD’s weaker-than-expected software Quality Assurance (QA) culture and its challenging out of the box experience. As fast as AMD tries to fill in the CUDA moat, NVIDIA engineers are working overtime to deepen said moat with new features, libraries, and performance updates.

Nvidia has 1000s of employees dedicated to CUDA, for free software! And the ROI on those investments is in the tens (or hundreds) of billions of dollars.

Alternatively, you can use hardware to sell software. Take our friends at Vast Data for example (who’re reportedly raising a round valuing them at $30B (!)). They sell software, that runs on storage boxes in data centers, to manage the data for AI workloads.

They initially sold integrated hardware and software. But in 2021, they stopped building hardware, opting to let partners do that for them. They still have heavy involvement in the configuration and design of the hardware, but don’t manufacture it themselves.

Now, customers buy the hardware from their partners, powered by Vast’s software. The beauty of this is that Vast gets the upside of the data center boom, but their revenue is recurring from software, so they don’t get the downside when the hardware investment cycle slows.

Use hardware to sell software!

The takeaway: Hardware is hard, but difficulty creates differentiation. If software gets commoditized, more value will flow to hardware. And this article is about finding differentiation in software. If a company can use hardware to get performance gains, it’s a wonderful way to build moats.

For next-gen hardware companies (semiconductor companies, for example), the decreasing cost to build software creates a new way to build moats and distribute your hardware.

2. Offer Vertically-Integrated Solutions

The other way to benefit from hardware is to offer vertically integrated software and hardware products. A company sells one product, at one price, that integrates hardware and software to provide the best customer experience possible.

We’ve seen many of the largest companies of the last three decades leverage this strategy to provide MUCH better customer experiences than incumbents: Apple, Tesla, SpaceX, The Hyperscalers, Anduril.

The basic premise is this: by controlling every piece of the user experience, you can more easily create magical experiences. This is why Steve Jobs meticulously reviewed every single piece of Apple’s products. As software gets easier to build, it becomes easier to own every part of the value chain.

We’re also seeing new players leverage this strategy like Radiant Nuclear, Base Power, and many others.

Packy McCormick has written a wonderful series on vertical integrator startups (I hope I don’t too grossly overcite his articles, but do go read them if you haven’t). The startups are integrating sets of proven technical components, and then innovating at the systems level: The integration is the innovation.

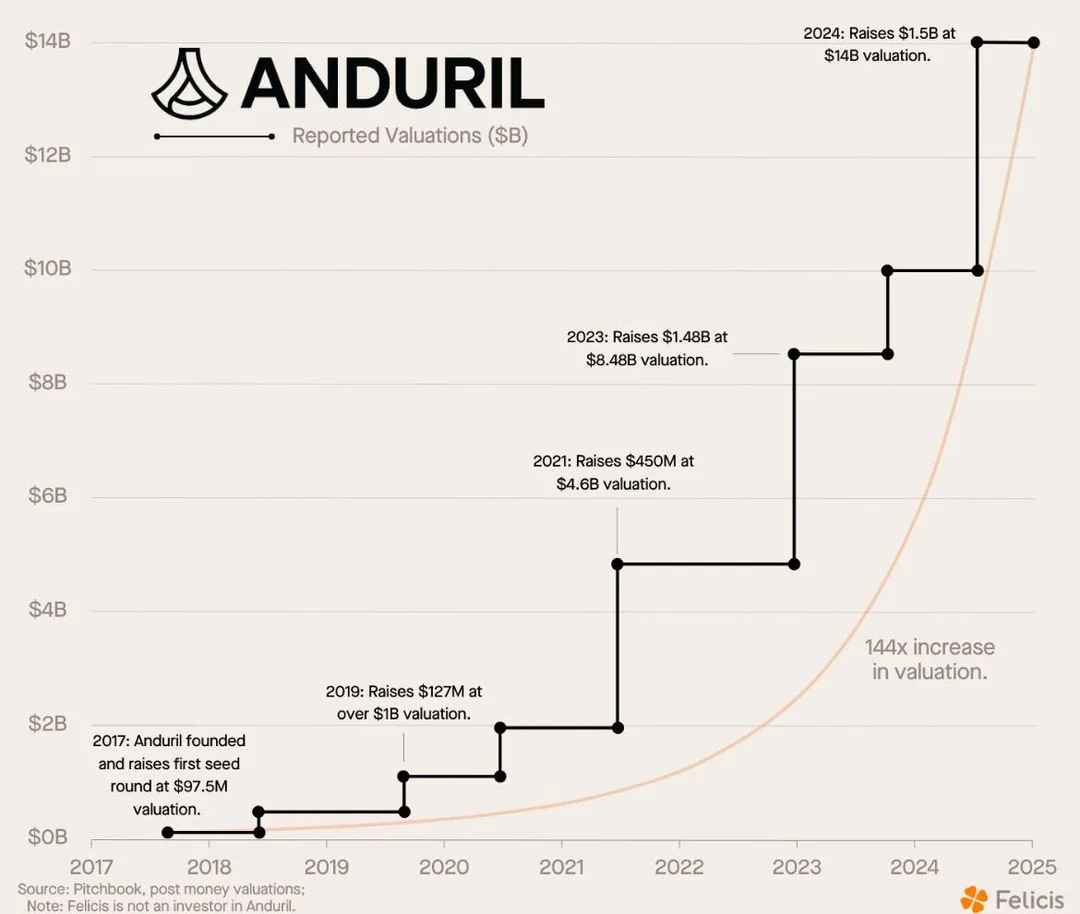

I’d argue Anduril is the perfect example of the modern vertical integrator (and what a rise it’s been, they’re up to $30.5B since this chart was made):

Pre-Anduril, the majority of contracts won by defense contractors were cost-plus contracts. By the way, can someone tell me a worse way to align incentives?

Combined with the consolidation and oligopoly of the defense contractors, all incentives were aligned AGAINST innovation.

Until companies like Anduril (and Palantir as its predecessor, but we’ll discuss them in a bit) came along. To win government contracts, they not only had to beat incumbents, but beat incumbents’ solutions so badly that they overcame the decades of inertia and relationships those contractors had built up. And the best way to do that was vertical integration.

They compiled one of the best hardware AND software teams in the world, and started selling integrated solutions, from watchtowers, to drones, to submarines. A lot of hardware, enabled by software. And it resulted in a better, faster, cheaper products that built a $30B company.

If you ask me one area I think will generate the highest “slugging ratio” of $10B companies over the next two decades, it’s this theory applied to healthcare, robotics, manufacturing, and more!

3. Offer Services

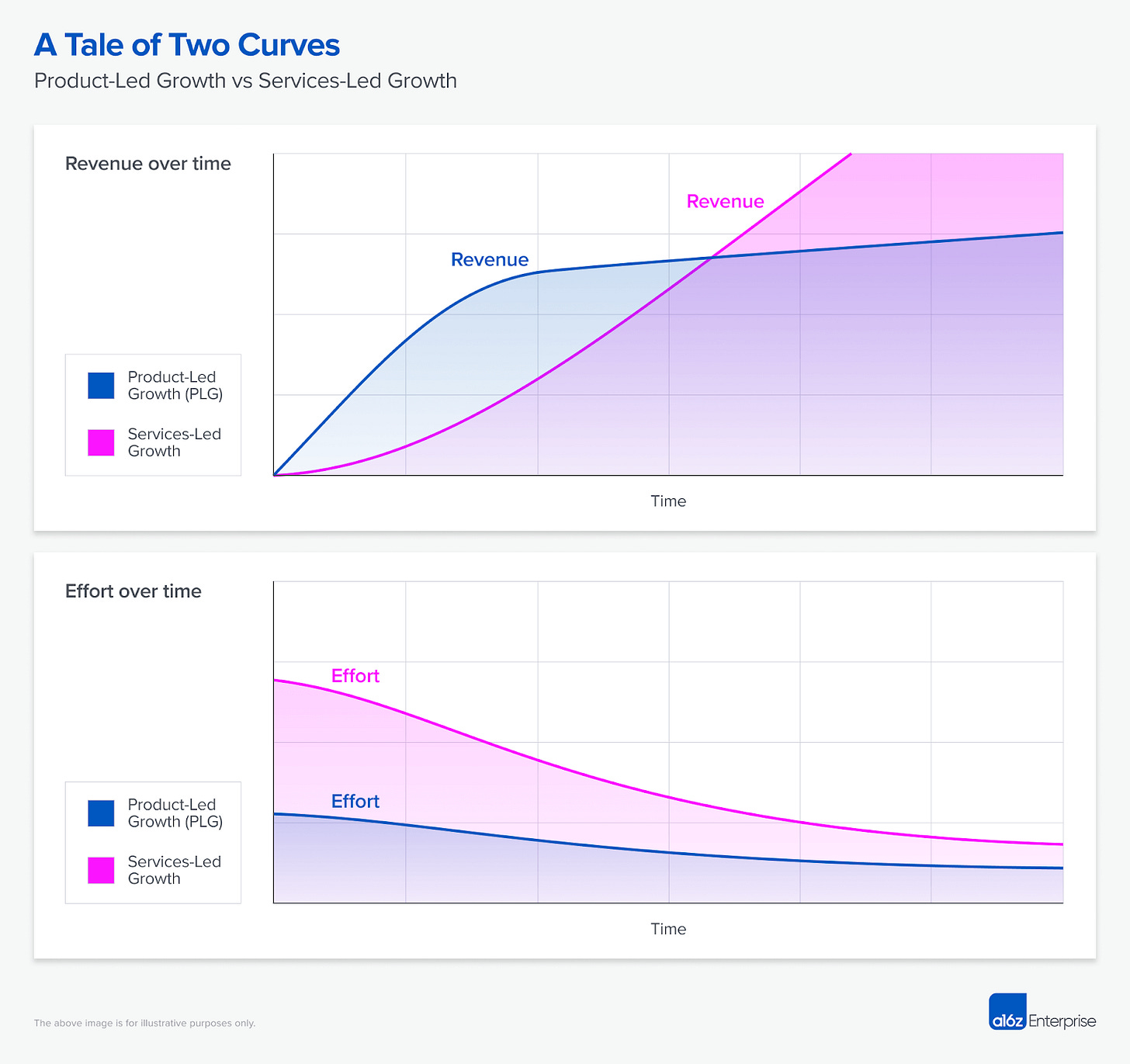

For as valuable as software has been, its promise has always exceeded its impact.

The problem with selling software is that you can sell it, but you can’t guarantee the customer uses it. And you DEFINITELY can’t guarantee they use it optimally. This statement gets put on steroids with AI.

Services, meaning including human labor with the software, help to prevent this. There are two applications of services in this context:

Forward Deployed Engineers: Help the customer implement the software; the more complex the implementation, the more valuable the services.

Sell services, not software: If an AI tool actually provides performance improvements, why not build a business around that tool and outcompete competitors with better prices and a better experience? Instead of taking a software-sized bite out of the value chain, you can own the whole thing.

For the Forward-Deployed-Engineering model, the logic goes like this:

Software is only valuable if it can be adopted. The barriers to adopting software are often the technical know-how of the adopter. For complex environments, like:

In financial services, integrating with mainframes and COBOL code

In healthcare, deploying software to systems with hundreds of clinics, large hospitals, and thousands of patients, with life-or-death consequences if there are mistakes

In government, well…you can imagine what it’s like to implement software in the government

In these examples, it’s not an option, but a necessity to provide implementation services. For a simple framework, the complexity of the industry directly scales with the success of the FDE model. Growth is slower, but it's got more durability!

Palantir has (now) famously pioneered the FDE model, which explains their success in selling government software. It also explains why they’re so successful in healthcare deployments. For projects, their teams go on site, leverage the Palantir platform, and co-build solutions to their customers’ specific problems.

On to selling services themselves. For this, I’d rather explain through a thought experiment: Why haven’t there been any large companies built selling AI to hedge funds?

The software is immensely valuable, very smart people have worked on these problems, and could raise money to sell the software. But the answer is if the algorithms actually provide alpha, it’s far more profitable to create a hedge fund, and leverage the software to generate alpha.

If you try to sell the software, the logic breaks down in two ways:

If the software doesn’t work, no one will buy it.

If the software does work, and you sell to many customers, the competitive advantage will be eaten away, making it less valuable and easier to copy.

If we now apply that logic to the legal world, a common AI use case:

You can sell AI software to legal firms, which are notoriously difficult buyers, in large part because of the misaligned incentives of hourly billing.

Or if the AI actually works, you can vertically integrate as a legal firm, get the 50% productivity improvement of AI, and outcompete the law firms who wouldn’t adopt the AI software. Over time, as AI automates more of the work, the firm collects more of the value, looking more and more like a software company.

So the basic idea of selling services, is that it’s far more valuable to sell “the work” than the software. Instead of taking a high-margin software-sized bite out of the value chain, you take a low-margin approach, but gobble up the whole thing.

Similar to how Steve Ballmer described Microsoft’s shift to the cloud,”You should expect us to have lower gross margins going forward, but we’ll make it up in volume.”

The two attempts to do this are in starting an AI-native startup or rolling up (acquiring) existing businesses and using their customers as a distribution network to deliver the value of AI. Both are logical strategies for creating a differentiated business model. (Whether or not this makes sense as a VC investment is worth its own article.)

Three recent examples of the rollup strategy, led by Thrive Holdings, are Crete (Accounting), Shield Technology Partners (IT Consulting), and Savvy Wealth (Wealth Management).

4. Process Payments

As the world stands today, companies still need to pay interchange fees on payments, regardless of who they choose. If companies can integrate payments into their platform, it provides another way to profit off of software without having to charge for it.

I was recently arguing with a friend on what Ramp’s valuation should be. His argument was that “it’s not real software revenue.” If we take a step back, the benefit of enterprise software is that it’s:

Recurring

Predictable

Hard to switch off of

In Ramp’s example, they give software away for free, then collect a % of expenses processed by Ramp’s expense cards, through Ramp’s travel platform, or through Ramp’s procurement tools. If a customer is using all three of those offerings, Ramp’s business is:

Recurring (and aligned with the success of the business)

Predictable (although less so than traditional SaaS contracts)

Hard to switch off of (same software switching costs as traditional SaaS)

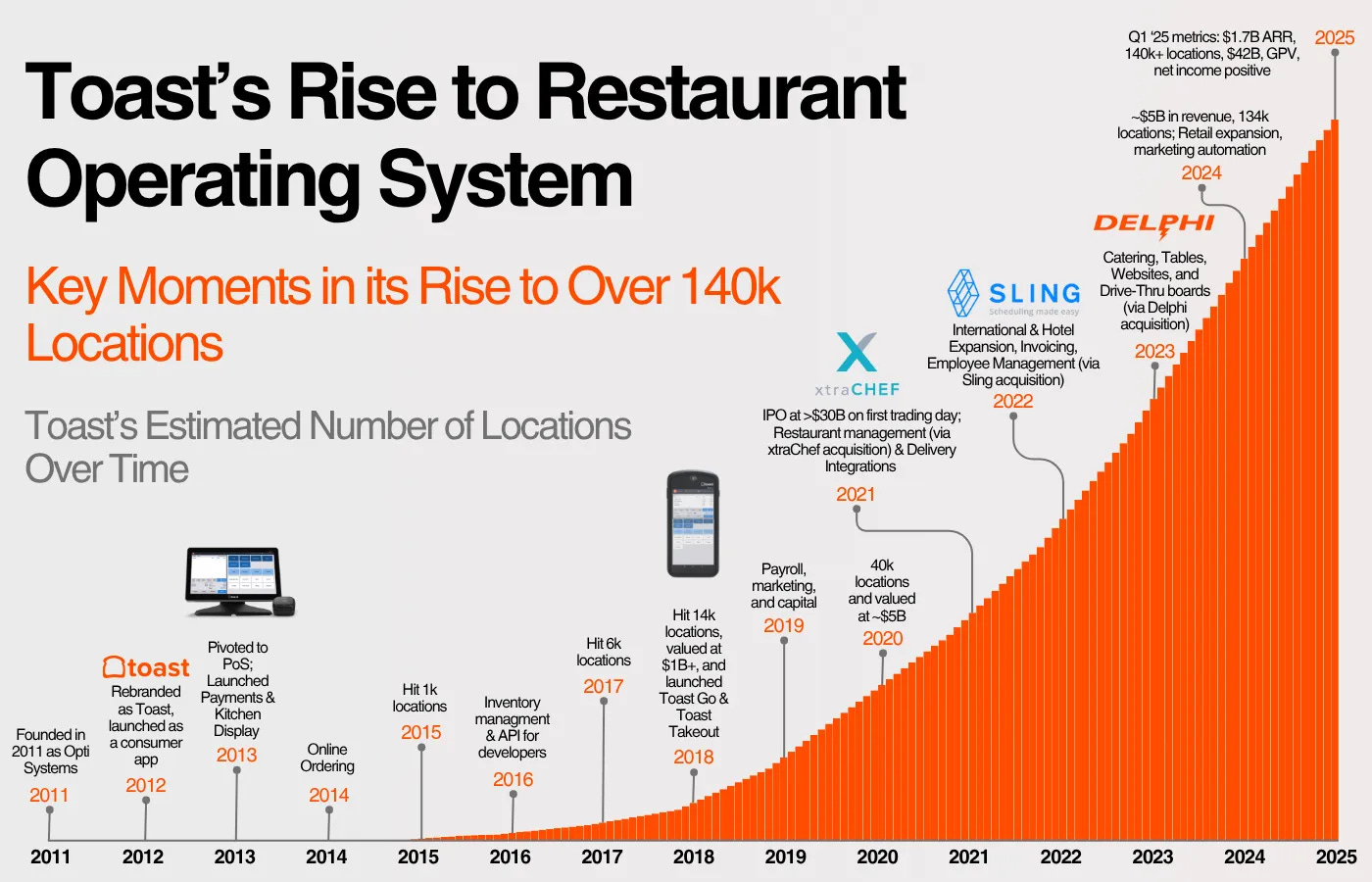

Ramp’s not alone. I talked about this in my Toast Deep Dive: getting restaurants to spend a lot of money on software is really hard. But getting them to pay for a payment processor is easier, they’re paying interchange fees either way!

In a world where enterprise software is more and more competitive, people will pay less for it. But if you give away the software for free, and can offer payments through the platform, it provides a different value prop for the customer:

You already have to pay interchange fees, you might as well pay them to us, and we’ll give you all of this software for free!

5. Sell a Platform

When I was working at Microsoft, one competitive advantage stood out over all others: the strength of their platform, and the ensuing ability for them to upsell through their distribution network.

Microsoft seemingly had a relationship with every single enterprise in the world. When they released a new product, they could give it away for nearly free, upsell through their distribution network, embed switching costs, and then raise prices.

Even better, a company’s already got data stored with Microsoft, oftentimes very high-value data, and so they trust Microsoft. Plus IT doesn’t need to manage another vendor, just add it on to the contract!

They beat point solutions over and over (and over) again with this strategy.

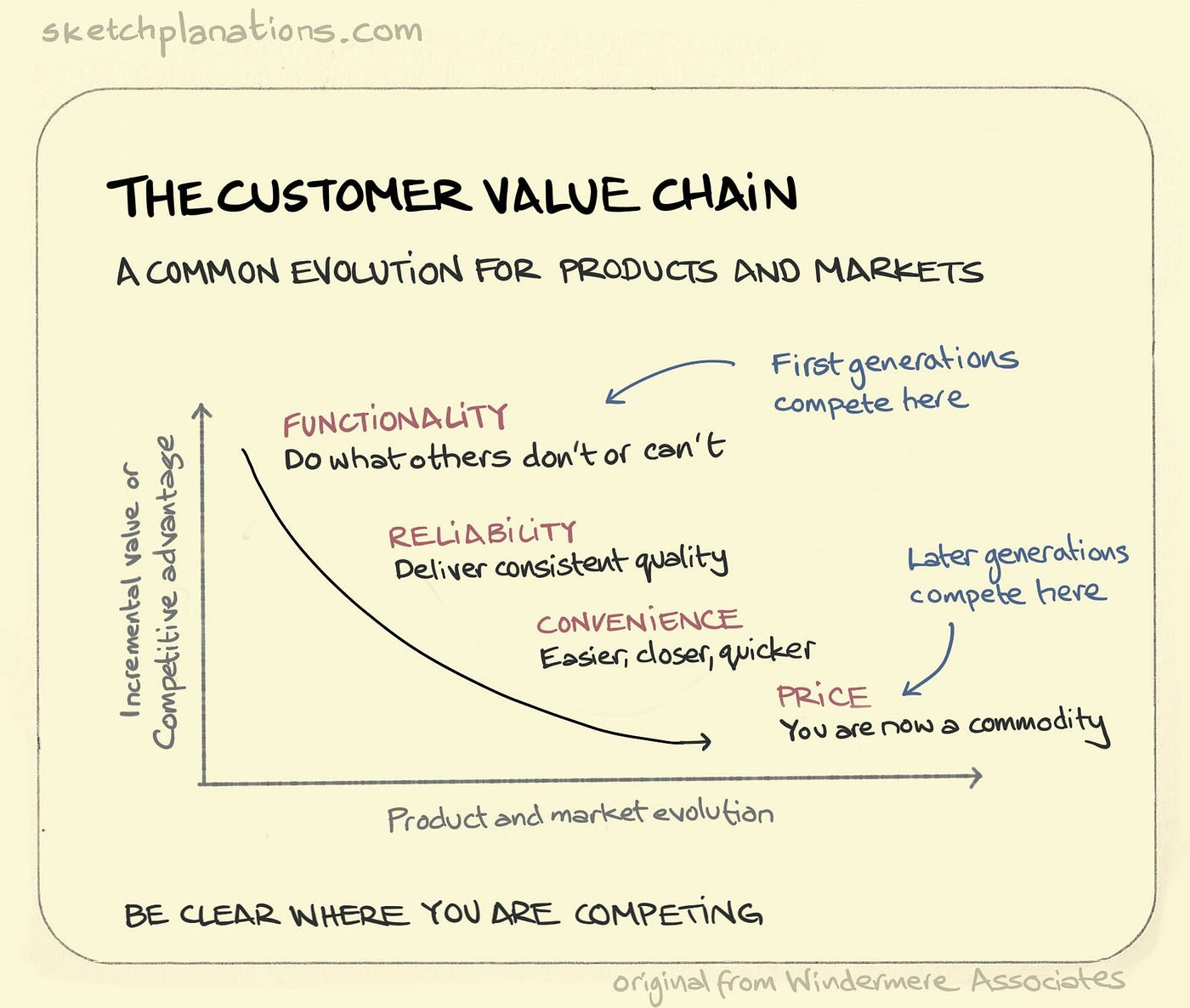

As industries consolidate, the variable for competition changes: from functionality, to performance, to convenience, to price (commodity):

My argument for building platforms is that we’re in the convenience phase of software. There’s not enough differentiation for customers to pay for point solutions, but they will pay for the convenience of not having to manage many different pieces of software.

Take the success of Rippling (now valued at $16.8B) as an example. Look at their launch announcement:

Today, we’re launching a best-in-class, all-in-one HRIS, payroll, and benefits system. But Rippling itself isn’t just an HR system. It’s a level deeper in the stack—a system for employee information that connects to all your key business systems and automates manual processes across the entire company, not just HR.

If there were ever a time to go to market with a platform, it’s now.

But even better, if there ever a time TO BUILD A PLATFORM, it’s now.

With the decreasing barrier to entry of software, it’s now possible to build a platform MUCH faster than ever before.

6. Advertising

The shortest and simplest of these micro-essays is centered on one fact: The two best business models of all time were built on “free software.”

They did so by aggregating attention, via network-effect-driven marketplaces. Obviously, if you can build network effects into your business, it’s a wonderful thing. But that’s very hard to do.

It also points to another fact: if you can own attention with software, you can monetize it.

In an age where attention is scarcer than ever, you can monetize it even more.

Consider this a prediction that we’ll see more and more “software as content”.

Brands will take unique data they have from their business, build out applications, and use it as another way to garner attention for their business.

For a mini example, look at Ramp’s AI Index. Ramp then gets shared thousands of times across articles for leveraging their data, building out lightweight software to visualize it, and telling the world about it.

7. Infrastructure, GTM, Inertia, and All the Reasons Theories are Brittle

Finally, what about the infrastructure that enables this shift?

I’d argue that open source infrastructure has been pioneering these business models from the beginning. Starting with Red Hat in 1993, offering services and compute built around Linux.

So I’ll create one more category: the infrastructure that enables “free software.” From cloud services, to hosting, to AI coding, to databases. The companies enabling this software to be built will collect a tax on each piece of it.

On top of that, distribution/marketing/sales, deep data integrations & switching costs, and any moats built through vertical-specific regulations are more important than ever.

The barrier to software development has been dropped to near zero. And with it, decreased the barrier of turning creativity into creation.

I remember the first time I used GitHub Copliot in 2022, then when I used Cursor in 2023, and then Lovable at the end of 2024.

Each time, I remembered feeling the same thing: that the barrier for creation is lower than every before. Anyone can build software, and anyone can build businesses.

It’s the best time in history for those who do want to build businesses. Hopefully, these playbooks help them do it.

As always, thanks for reading!

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not investment advice and should not be used as such. Investors should do their own due diligence before investing in any securities discussed in this article. While I strive for accuracy, I can’t guarantee the accuracy or reliability of this information. This article is based on my opinions and should be considered as such, not a point of fact. Views expressed in posts and other content linked on this website or posted to social media and other platforms are my own and are not the views of Felicis Ventures Management Company, LLC.

This is just brilliant. I think you nailed it for the practice of law.

Your 7 business models may end up being the exact right ones for the current moment in time. But I can't help but feel that there is a potential flaw in the logic between your points 1 ("Software is getting cheaper and easier to build, and that will only continue.") and 2 ("Because of that, technical differentiation will be harder to create and maintain.").

The arc of time over which software has gotten cheaper and easier to build is very long, and way predates AI. Modern IDEs, cloud computing & hyperscaler building blocks, democratization of access to coding knowledge, better collaboration technology over the internet, Stack Overflow and similar, larger populations of eager developers in developing nations, etc.... these have lowered costs and barriers to building software and have been trends going over decades. (you know all this well, obviously)

But those reduced barriers have not led to decreased technical differentiation as far as I can tell. Rather it seems like we have sets of dominant software franchises just like we did in the 80s and 90s and 00s, only software is now much better, much more sophisticated and scalable and high-performance, and way more intricate. So rather than "cheaper/easier" implying "differentiation down, moats are lessened", it seems to have implied "product quality improves in lockstep with productivity improvements; moats and differentiation remain approx. unchanged in aggregate".

I think it would be a lot different if software development productivity improvements were uniquely accessible to new entrants in a way they weren't to incumbents (that would make it more like the cloud transition*, where it made more sense to start a new SaaS company than to retrofit an on-prem company to cloud). But as far as I can tell, the kinds of software development advances we're seeing in AI are equally available to incumbents (at least the ones who have adaptable cultures) and to entrants, which means that while, yes, new startups can build 0 to 1 products faster than ever before, incumbents can use AI to build further differentiation into their platforms faster and extend their leads. So that again would be the pattern of the quality bar rising while the ability to maintain differentiation is somewhat static.

I'd certainly be curious for your pushback here.

*(if it turns out that brand new AI-first software is just plain better at solving customers' problems than incumbent software with AI incorporated into existing workflows, then I agree that the differentiation dynamic would quickly shift away from existing franchises and make it harder for everyone to maintain share. But I don't think we know enough to say whether that's true or not.)