2025 Annual Letter

An Estimation of Underestimations

It’s hard to say something that hasn’t already been said. I’ve felt it more and more as LLMs can now say anything we ask them to. More than ever, quality matters so much more than quantity, ergo the delayed publishing pace from me on this newsletter.

So my goal for this publication in 2026 is to make everything I publish here worth reading. Attention is scarcer than ever, and I see it as my responsibility to respect all of yours.

With that in mind, why write an annual letter in the first place (by definition, a time-constrained, not quality-constrained artifact)?

A few reasons:

I have a special affinity for the annual letter. I’ve gotten tremendous value from reading the greats’ musings on investing, and my goal is to provide a bit of value in mine

It’s a selfish endeavor. As people outsource more thinking and writing to AI, the value of doing it well increases dramatically. While I make no claims to either, structuring my thoughts on common investing mistakes has been quite valuable for me

In a world where more knowledge work is being automated, good questions and ideas become more valuable than good answers

Onto the topic of the annual letter (what I believe is a good question): why do investors so often underestimate great companies, and how can we avoid those traps?

An Estimation of Underestimations

Investing, by definition, is a game of underestimations: seeing something that others haven’t, OR acting in a way that others don’t. Our job is to generate value by taking advantage of that underestimation.

Plus, as a midwesterner from a town of 500 people in Indiana, I can’t help but have a soft spot for the underestimated.

I’m summarizing my investment thesis these days very simply: I’m looking for the underestimated. Underestimated people. Understand businesses. Underestimated opportunities.

So what more valuable topic to discuss than an observation of the most common underestimations I’ve seen in the investment industry, an estimation of underestimations if you will!

I’ll be framing much of my investment philosophy today through the following underestimations1:

The Influence of Consensus

Incentives

How much History Rhymes (and how little it repeats!)

Probabilities & a Focus on the Inputs

The Long-Term: Destination Analysis, Compounding, and Concentration

The Dynamic Range of Humans

By definition, an underestimation can only exist if others aren’t properly estimating it. Which makes the influence of consensus the foundation for the rest of this essay2.

One: Underestimating the Influence of Consensus

From my observation, the most common investment mistakes come from overweighing others’ opinions on an investment. In the words of Neil Mehta, “the laws of great businesses are the laws of great businesses.”

This is especially prevalent in private markets where information is less available; so when there’s uncertainty, investors tend to look elsewhere for confidence. If they see it from other investors, a fear of missing out takes care of the rest. And if they don’t, they hesitate, as it’s unnatural to make decisions under uncertainty.

But I’ll argue it’s the lack of analysis, not the lack of information, that’s the most frequent bottleneck. From Nick Sleep’s 2012 letter:

In today’s information-soaked world there may be stock market professionals who would argue that constant data collection is the job. Indeed, it could be tempting to conclude that today there is so much data to collect and so much change to observe that we hardly have time to think at all. Some market practitioners may even concur with John Kearon, CEO of Brainjuicer (a market research firm), who makes the serious point, “we think far less than we think we think” - so don’t fool yourself!

If the world was information-soaked in 2012, it’s drowning in 2025!

The analysis (i.e., the independent thought) is the hard part; so when there’s “consensus” from other investors, choosing that company becomes “the easy path.”

At the same time, most investment firms are not structured well for investors to make non-consensus decisions. Personal “mistakes”3 are costly in the investment industry, so herd behavior is also “the safe path.”

That said, there’s reason for optimism! The benefit of the investment industry’s enduring herd behavior is that there’s plenty of opportunity to think for ourselves. And as people outsource more of their thinking to LLMs, I suspect that opportunity will become even more enduring.

Two: Underestimating Incentives

People tend to act in their own best interests; ergo, incentives are the driving force in our world. Incentives are like gravity, and fighting against either should be viewed similarly (it’s going to be tough!).4

The epitome of this is the US healthcare system, based on a fee-for-service model. This incentivized providers to provide as much care as possible, not the right amount. And it incentivized payers (insurance companies) to reimburse only the care they think is required.

This led to an incredible burden of documentation on providers to prove they delivered “the right amount of care”; and as a result, a ton of admin waste throughout the whole system (more than a trillion dollars a year!)

On a more optimistic note, I spend much of my time with healthcare startups, as LLMs have created the ability to automate much of this admin work (due to the fact it’s based on nuanced text-based information). This cuts costs for providers AND payers, and it provides a much better experience for clinicians and patients.

It aligns incentives for everyone involved!

When a company aligns incentives for all parties involved, and even better has a compounding competitive advantage with it, underestimate it at your own risk!

In summary, some wisdom from Charlie: “Never, ever, think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives.”

Three: Underestimating how much history rhymes (and how little it repeats!)

It’s no surprise to anyone reading this how much I value history. That said, it’s surprising to me how often it’s misrepresented. It’s human nature to look at the immediate past and extrapolate. But it seems to me this leads to far more mistakes than not.

To get a bit practical for VCs, the two most common analysis mistakes I see:

Underestimating market size because the current market is “small”

The lack of a large existing market today leads investors to underestimate a startup’s ultimate market size, especially when there’s a catalyst to drive market expansion.

My favorite example is Aswath Damodaran’s now-infamous estimate of Uber’s market size and Bill Gurley’s response:

A decade ago, Aswath Damodaran (The Dean of Valuation) estimated Uber’s value to be approximately $6B based on the total TAM and market share. Bill Gurley argued that this number was off by a factor of 25x based on an underestimation of both variables. Uber is now worth $200B (33x Damodaran’s estimate)

In short: latent demand for a service, and a new technology that unlocks the ability to service that demand, is a wonderful thing. Regardless of “existing market size”.

Underestimating a company’s value due to “low multiples” or “public comps”5

A common valuation practice is to take today’s revenue or projected revenue over X years into the future, then apply a “reasonable” multiple to that revenue to arrive at a potential valuation. Investors typically get that multiple from “comparable” companies in the same industry.

But this leads to comparing a new company, potentially with a completely different cost structure and competitive advantages, to an incumbent.

The classic example here is Tesla being compared to existing auto companies (and their multiples), leading many investors to underestimate what Tesla could create with new technologies and cost structures.

And as a reminder, multiples are a short-form proxy for the cash flows a company will generate going forward: a second-order effect of business quality!

So companies with higher multiples tend to be much stronger than companies with lower multiples. Which means, all else equal, you’d rather invest in a startup with “low multiple public comps” than high multiple ones. The exact opposite of what much of the investment industry does!

All in all, both of these ways of thinking typically lead to quite a lot of underestimations for companies without a direct historical precedent.

Four: Underestimating Probability-Based Thinking

More often than not, when an investor is discussing investing in a company (especially startups), it’s a matter of “Do I think this company will be successful or not?”

The error here is that our world works in probabilities. Each decision is based on a tree of possible outcomes, with probabilities attached to each outcome. And by using absolutes, you increase the odds you’ll underestimate an outlier company.

Let’s look at Nvidia’s recent $20B pseudo-acquisition of Groq as an example. When the company was founded, if you asked the question, “Will this company work?”; Most investors would’ve said no, saying Groq will fail because the technology is complex, the costs to develop semiconductors are high, go-to-market is hard for semiconductor startups, and Nvidia is the Hulk.

They probably would’ve been right, and they would’ve missed the investment!

So you’d get much closer to making the investment if you asked the question, “What’s the probability Groq will be successful and/or disruptive to Nvidia AND what will happen if so?”

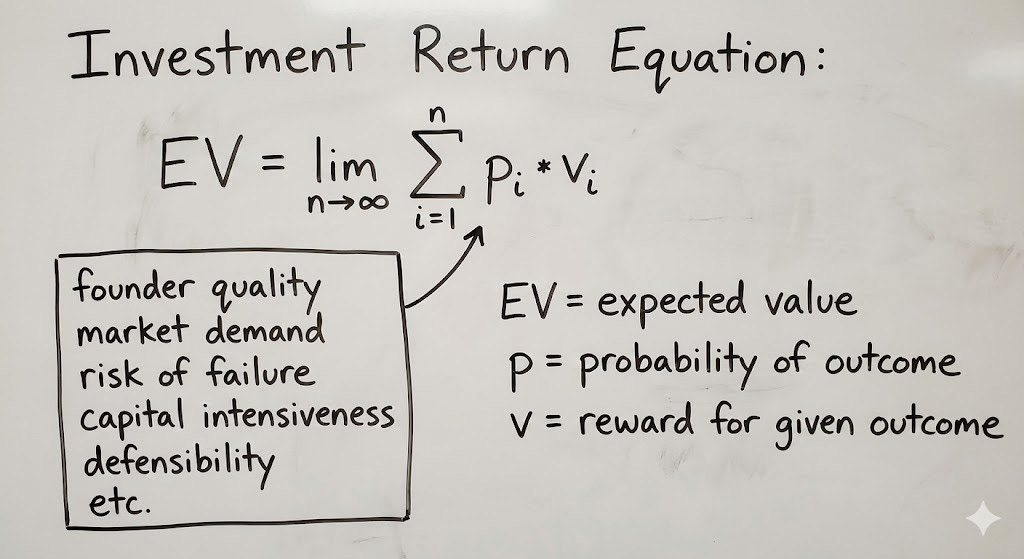

Now, a general equation for investing in a company goes like this (and this just means the sum of all the probabilities times the reward for each probability):

So the question “Will this investment work?” isn’t the right question at all! The question is “what’s the probability this investment will work and what outcome will come of it if so?”

In VC, in particular, an interesting situation arises in which a small number of companies drive the vast majority of returns. So in the above equation, the only probabilities that matter are the ones attached to very large outcomes.

So, in the words of Bill Gurley, “What can go right?” becomes the most important question to ask about a startup.

A note on inputs over outputs:

Implicit in probabilities is a focus on the inputs, not the outputs.

To continue the Groq example from above: let’s say Groq does fail to raise their last funding round and goes out of business. People would’ve seen that investment as a failure instead of a huge success!

So the key point is this: it’s the same investment regardless of the outcome.

Focus on the inputs you can control, let the outputs take care of themselves. Any mistakes along the way should be viewed as learning opportunities. As Nick Sleep said in his 2008 letter:

We would counsel you to think about the inputs to investing rather than the outputs. It is in times like these that the hard psychological and analytical work is done and the partnership is filled with future capital gains: this is our input. The output will come in time.”

Five: Underestimating the Long-Term

I continue to be convinced that a longer time horizon is a meaningful competitive advantage in today’s investing world. There are a whole host of reasons to not invest in a great company in the short-term (and often lots of good reasons to invest in not-so-great companies in the short term!)

To combat this, I operate under a few assumptions:

A small number of companies create the vast majority of value (this is true in both public and private markets!)

Most of that value is typically created “later” in the company’s life (meaning durability is just as important as growth, in the words of Peter Thiel)

Those companies tend to have a compounding advantage that makes them better with time, and that compounding advantage is identifiable earlier than most realize

Some might call that last point “destination analysis.” Said differently, it can be easier to predict the long-term than the short-term.

And when you have figured out the long term (or a decent probabilistic view of it and a willingness to update those probabilities with time), let compounding do its magic!

Now it’s human nature to focus on the short-term, but it’s also human nature to underestimate the value of compounding; for some reason, we just struggle to internalize exponentials. Even with the risk of suffering from hindsight bias, I’ll share a few data points:

From Warren Buffett’s Biography: Several times every year a weighty and serious investor looks long and with profound respect at Coca-Cola’s record, but comes regretfully to the conclusion that he is looking too late. [For the record, when that book was published in 1995, Coca Cola’s market cap was roughly $45B. Today it’s $300B.]

Shopify, at nine years old, IPO’d at a roughly $1.3B valuation in 2015. It’s now worth $210B (a 161x for anyone counting).

Nvidia was worth roughly $15B in 2015, an incredible outcome for a company only 22 years old. It’s now up ~293x that, in years 22-32 in founding.

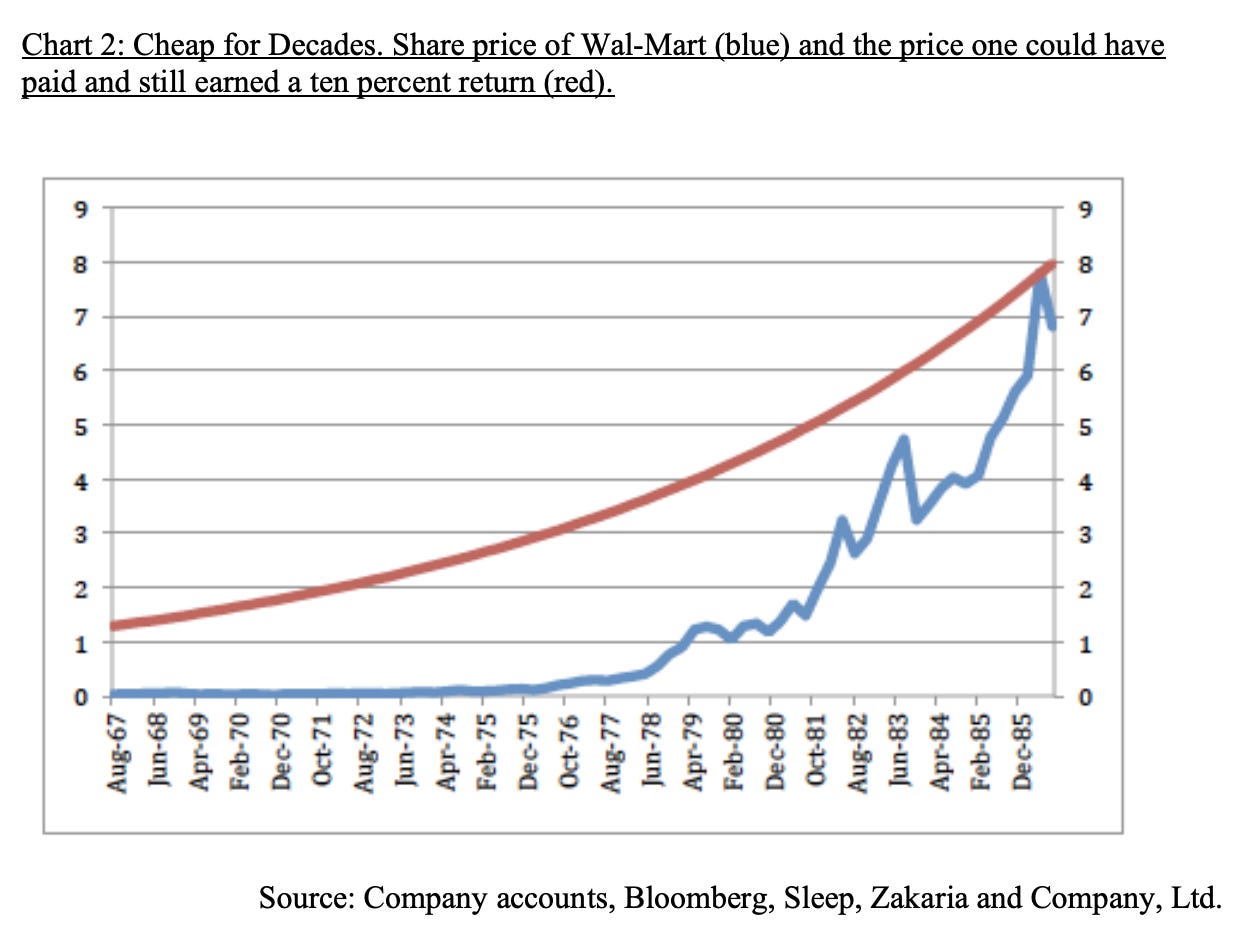

One more: take a look at the price you could pay for Wal-mart and still get a 10% annual return!

It’s easy to underestimate how long it takes for a great business to emerge, and it’s easy to underestimate how large the truly great ones will become.

A note on underestimating concentration:

Once you’ve found one of these incredible businesses, it’s worth concentrating deeply in those businesses. They’re even rarer than we think.

To abstract the point a bit: in a world where distractions are greater than ever, it’s never been more valuable to concentrate on fewer ideas.

When there’s so much information, adverse selection is a very hard problem to solve, and can only be accounted for with deliberate focus.

The most readily available information may not be the most valuable. The most available opportunity often is not the most important. The company you can invest in may not be the one you should invest in.

Six: Underestimating the Dynamic Range of Humans

Finally, it’s easy to miss how truly special people can influence the world around them.

I’ll take this idea a step further, take this quote from Warren Buffett:

“It was an agrarian economy a couple hundred years ago…Very hard, you know, to get 20 times the wealth of the next guy because you were a little bit better farmer. But if you’re better at some skills now, you can become incredibly wealthy at a very young age … You get to capitalize [the] value of an idea. And so the wealth moves big time, even on an anticipatory basis.”

I’ve made it this far without mentioning AI too much, but I’m afraid I’ll have to break that celibacy here. From my observation, the discovery of transformer-based models are new, but artificial intelligence isn’t. It’s the continued evolution of 50 years of computing, slowly automating knowledge work to make us more efficient.

In summary, giving us leverage.

As I think about AI’s impact in 50 years, I don’t think AI will automate all of human knowledge work (consider me a humanist!), but I do think the top percentile of people will become even more leveraged.

With that, the dynamic range of humans will expand even further. Outside of the societal implications of this furthered divide, it’s led to one operating assumption I’m moving forward with:

Find the people who will be in the long tail of the dynamic range of humans, and figure out how to work with them for the next 50 years.

I feel grateful to have started that journey (thank you to the incredible folks who have invested time in me), and I hope to continue it for decades to come.

If there’s anyone left reading (surely there’s someone!), I’ll leave you with one point: these ideas are easy to say, and hard to do. There must be a conscious effort every day to pursue them.

I’ve no doubt that as I go back and read this letter in a year, it’ll seem obvious and rather rudimentary. I hope so, at least. Perhaps it means I learned something.

In the words of Nick Sleep, ”When I finish writing these letters, I am happy with them, at least happy enough to send them out. I make a habit of re-reading them sometime later and frequently they disappoint. It is as if the letters have a short shelf life.”

I’m going in eyes wide open!

I feel compelled to end this letter as I did my last one, with a thank you to those willing to invest their time into me (including those who read this newsletter regularly).

I don’t take the opportunity lightly to do what I love for a living. In large part, that’s because of the support from you all and those who have heard my thoughts and deemed them worthy of a bet. Thank you.

Onwards and Upwards. To 2026.

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not investment advice and should not be used as such. Investors should do their own due diligence before investing in any securities discussed in this article. While I strive for accuracy, I can’t guarantee the accuracy or reliability of this information. This article is based on my opinions and should be considered as such, not a point of fact. Views expressed in posts and other content linked on this website or posted to social media and other platforms are my own and are not the views of Felicis Ventures Management Company, LLC.

I believe most of these underestimations stem from three hard-wirings of the human brain: humans are social animals (consensus meant not getting kicked out of the tribe), we evolved with scarcity (short-term focus), and we think in absolutes rather than probabilities (faster decisions, better for avoiding sabertooth tigers).

Some disclaimers:

1. Apologies for how often I will quote other investors in this letter. Like I said, it’s hard to say something that hasn’t already been said!

2. While I’m 100% confident there’s not a new idea in this letter, I’m also 100% confident these ideas are not fully grasped by the industry, given that I see these mistakes daily. In the words of Tom Stoppard (via Nick Sleep), “If an idea is worth having once, it’s worth having twice.”

3. This is meant to be a journal entry, not a sermon; I’m guilty as well

4. This will be more catered towards mistakes in venture capital, but I’m confident they stretch across most of the investment industry.

5. Saying these lessons is easy, writing them down is marginally harder, practicing them is much much harder.

I think mistakes are a positive indicator of success if used wisely.

See the point above on “career risk” for investing in non-consensus companies, another reason incentives lead to missed opportunities.

A public comp (comparable company analysis) is when you value a private company based on the stock price multiples of similar public companies.

Truly an underestimated piece of work .. just outstanding ..

incredible read!